To mirror yesterday’s conversation on training around pain, today’s post delves a little deeper into a specific area that many lifters tend to have issues with:

Not enough bicep curl variations in their programForgetting to remove their shaker bottle from their gym bag for week- Knees.

The knees are a vulnerable joint and there are myriad of reasons why they can become achy, sore, cranky, or any other similar adjective you want to put here.

Sydney, Australia based physical therapist and trainer, Dane Ford, was kind enough to write this straight-forward article on some of the root causes of knee pain and ways to address them on your own.

Enjoy!

Knee Pain When Squatting?

Squatting is an essential part of most people’s fitness routine, and it can be extremely frustrating when you experience sore hips or knees when you squat.

Today I’m going to share four killer exercise variations that will help take some pressure off your knee joints!

No matter what level your fitness is at – whether strength training or just getting healthy again after injury – these tips should work their magic in no time flat.

Let’s get started.

The Goods

Box squat.

The first variation for those who experience knee pain when squatting is the box squat. A box squat will strengthen your quads, glutes, and hamstrings. It’s also a great way to improve your squatting technique.

You’ll need a box squat or a bench around knee height to do a box squat.

- Start by placing the box behind you.

- Then, position your feet shoulder-width apart and push your hips back.

- Next, bend your knees and lower yourself until your bottom touches the box. Pause for a second, then stand back up.

Step-Ups

Step-ups are another great variation for people who have knee pain when squatting. This exercise works your quads, hamstrings, and glutes and is a great way to build lower body strength.

- To do a step up, start by placing your right foot on a box or bench.

- Then, push off with your right foot and raise your body up until your leg is straight.

- Pause for a second, then lower yourself back down.

- Focus on keeping the hips level.

- Start with a smaller step, and increase the step height as your body allows.

Hip Thrusts

Hip thrusts are a great exercise for people who want to build stronger glutes. This exercise can also help relieve knee pain when squatting by taking the pressure off your knees.

- To do a hip thrust, start by sitting on the ground with your back against a box or bench.

- Place your feet flat on the ground and raise your hips until your thighs and torso are in line with each other.

- Pause for a second, then lower your hips to the starting position.

- Progress this exercise by adding weight at your hips, like a barbell or plate.

Banded Crab Walks

Banded crab walks are an excellent exercise for people who want to build stronger glutes and legs. This exercise can also help improve your squatting technique by making it easier to push your knees out over your toes. This is a golden exercise for dealing with knee pain when squatting.

- To do a banded crab walk, start by placing a resistance band around your feet. (You could place it around your knees or ankles, but the further down your legs, the harder the exercise will be).

- Then, step one leg out to the side as far as the band will allow.

- Keep the hips level, and the shoulders stacked over the hips.

- Next, step in with the other leg.

- Repeat.

Causes of Knee Pain

When addressing knee pain during squats, it’s important to understand some of the common causes. This way, you can be sure that you’re taking the right approach to fix the underlying issue. Here are three common factors which can contribute to knee pain when squatting:

Improper Form

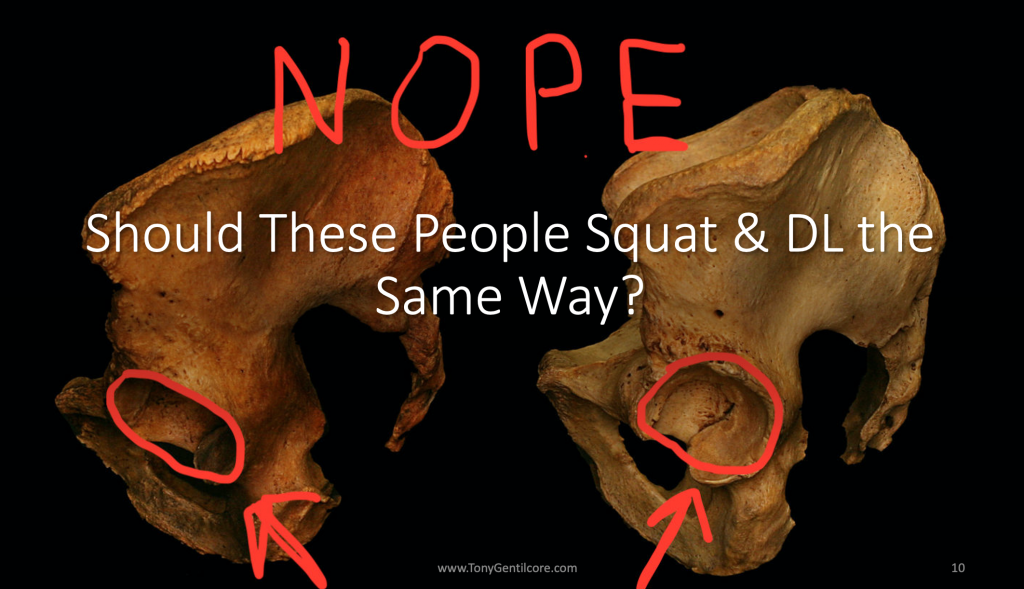

Whilst there is no such thing as textbook technique, using ‘adequate’ form allows you to engage the right muscles when you lift and minimize injury risk. If you don’t utilize adequate form when you squat, the load in certain areas like your knee joints will be increased, instead of having the load evenly distributed through your entire body.

Your ideal squat stance will be determined by the bony alignment of your joints and other anatomical factors.

Overuse

Our body’s tissues all have a maximum tolerable capacity. This means that we need to be able to go hard enough in the gym to stimulate adaptation and promote strength, whilst not overloading ourselves to the point of tissue injury.

Giving your body time to recover with rest or a de-load week every now and then is a great start, to allow proper cell regeneration, repair and adaptation to occur.

Adding variety into our movements is another great option to avoid overuse. Beyond the exercises we’ve covered above, mixing back squats with front squats, goblet squats, or other squatting variations will help to strengthen the squatting movement whilst providing a slightly different stimulus to our tissues, and reducing the overload injury risk.

Bad Shoes

If you’re wearing shoes that don’t provide adequate stability when you squat, then this can put unnecessary strain on your knees.

Be sure to wear shoes that provide you with a solid foundation from which to lift.

Health Conditions Related to Knee Pain

So now that we understand some of the mechanisms that can contribute to knee pain during squats, how do we know which structure in the knee is causing pain?

Knee pain can present as a number of different conditions depending on the injured structure. This can include:

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

PFPS or patellofemoral pain syndrome is a condition that affects the knee joint. It’s characterized by pain in the front of the knee and around the patella or kneecap, and is common in those who love to squat.

If you have PFPS, you might experience pain when climbing stairs, squatting, or sitting for long periods.

IT-Band Syndrome

ITBS is a condition that affects the iliotibial band, which is a long strip of connective tissue that runs down the outside of the thigh from the hip to the knee, and normally presents as pain on the outside part of the knee. But squatters need not worry too much about this – ITBS is much more common in runners rather than lifters.

Patellar Tendinopathy

Tendonitis is the inflammation of a tendon, which can occur in any tendon in the body. However, Patella tendonitis presents as pain just below the knee cap. If you perform a lot of explosive movements like box jumps, or fast tempo squats, you should be aware of patella tendinopathy.

Arthritis

Arthritis is a condition that causes inflammation in the joints. The two most common types that can cause knee pain are osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Osteoarthritis is a degenerative disease that causes the cartilage in the joints to break down. This can cause pain in your knees, as well as other joints in your body.

- Rheumatoid arthritis is an autoimmune disease that causes the body’s immune system to attack the joints. It may cause swelling and pain around the knee, leading to pain, stiffness, and inflammation.

Load management is key in managing arthritis. This is because we want to keep the muscles around the joint nice and strong, without irritating the joint too much.

How to Prevent Knee Pain When Squatting

Aside from performing some of the killer squat variations listed above, you can do a few other things to prevent knee pain while squatting.

Warm Up Properly

A good warm-up will help to increase your heart rate, loosen up your muscles, and make your body’s tissues more elastic. I recommend doing a light jog or bike ride for 5-10 minutes, followed by some dynamic stretching.

Use the Correct Weight

Another important consideration to prevent knee pain while squatting is to use the right weight. If you go too heavy too soon, it will put extra stress on your knees and could lead to pain. Utilize progressive overload by starting with a light weight and gradually increase the amount of weight you’re using as your body gets stronger.

Blood Flow Restriction Training

Another great way to improve strength whilst using light weight is by incorporating Blood Flow Restriction Training into your routine. This involves using a BFR band to reduce venous blood return from your muscles, making them work harder.

This means that you can use lighter loads to achieve the same result from your workout. BFR training can be a great addition if you are struggling with knee pain from squatting or trying to train with an injury.

Use a Smaller Range of Motion

Squatting through a smaller range of motion by reducing squat depth will reduce the load going through the knee joint, and is a great way to modify the exercise if you are struggling with pain.

Listen to Your Body

If you still experience knee pain while squatting, stop the exercise and rest for a few days. If the pain persists, consult a doctor or physical therapist.

Wrap Up

If you’re experiencing knee pain when squatting, try one of the variations I suggested and see how they work for you. Remember to always start light and gradually increase the weight as your body gets stronger.

And, most importantly, have fun with it! Squatting can be a great way to improve your fitness level and get in shape, but only if you do it correctly and safely. Give these variations a try and let us know how they work for you.

About the Author

This article was written by Dane Ford, the founder of Lift Physiotherapy and Performance in Sydney, Australia. Lift Physio aims to help you overcome injury, optimize your health, and unlock your full movement potential.

Scott Hansen is a Bostonian transplanted in Southern California, a strength/fitness/wrestling coach, educator, sub par surfer, and die hard New England sports fan.

Scott Hansen is a Bostonian transplanted in Southern California, a strength/fitness/wrestling coach, educator, sub par surfer, and die hard New England sports fan.