Today’s guest post comes courtesy of Zak Gabor, a MA-based physical therapist and strength coach. His alma mater – Ithaca College – also happens to be my alma mater’s – SUNY Cortland – sworn enemy.

But he’s cool…;o)

Enjoy!

Not only can tapping into your posterior chain get you extremely strong, help improve athleticism and give you the butt of your dreams, it can leave you significantly less injury-prone, especially with low back and knee injuries.

Photo Credit: Dr. John Rusin

I am here to discuss how and why posterior chain strength needs to be a priority in training (that is, of course, if you want to decrease your chance of getting injured.) Training your posterior chain doesn’t guarantee injury prevention but it sets you on the right track for building a strong foundation.

What is the Posterior Chain?

In the strength and conditioning world, the posterior chain consists of the erector spinae, gluteal muscles, hamstrings, and gastroc/soleus complex.

Note from TG: “Posterior Chain” was also the original name of Thor’s hammer.

But it actually wasn’t.

Why is the Posterior Chain So Damn Important?

This is an area that I am extremely passionate about. What can I say, I’m a butt guy, but for good reason.

I truly believe that incorporating posterior chain strengthening into training can save tons of money on healthcare costs for low back and knee injuries, but more importantly, keep you healthy!

As the PT profession is constantly evolving, my goal is to get clients in the door and teach them ways stay healthier, versus having patients in for rehabilitative purposes.

Lets dive into two of the major joints that are especially vulnerable to injury in the lack of adequate posterior chain strength:

Low Back:

Oh yeah, baby.

Over $80 billion spent each year on low back in healthcare… simply unacceptable.

To me, if you know how to strengthen your posterior chain, that means you know how to hip hinge (i.e. load the glutes and hamstrings effectively while keeping lumbar spine neutral). For anyone who knows what a freak I am about preaching this movement pattern, this right here is the primary reason why!

Am I saying that if you can hip hinge you will never get back pain? No. I am saying that understanding the hip hinge pattern will give you a much better chance at preventing low back pain. The simplified reason is two fold:

1) Lifting loads from the ground with a neutral spine= less likely to hurt low back

-Now, now, not trying to be dogmatic, but research don’t lie.

Spines ARE resilient, we need to be able to tolerate both flexion and extension.

Yet, if you are like me, and respect the work of one of the most influential low back researchers (Dr. Stu McGill) then you know that repeated flexion especially under loads; leave the lumbar spine vulnerable to injury.

Therefore, learning how to properly hip hinge and maintain a neutral, stiff, spine throughout the movement can not only prevent injury, but can also get you the butt of your dreams. Enter strengthening the posterior chain.

2) Strengthening posterior chain = less likely to hurt low back

Simply put, a strong butt (Gluteals) will decrease your risk of low back injuries.

There is a ton of research out that indicates how important gluteal strengthening is for low back rehab. Lets simplify this in the pre-hab lens.

Glute Max is one of, if not the most, powerful muscles in the human body. Unfortunately, most individual’s glutes are offline thanks to endless hours of sitting. If we can strengthen the most powerful muscle in the body (which just so happens to neighbor and play intimately with the lumbar spine), wouldn’t it make sense that it would be good protection for the lumbar spine? Just sayin’

Knee:

The knee gets a little bit more technical, but I will try to keep it simple.

The knee as a joint is extremely vulnerable, to say the least.

It is literally two bones sitting on top of each other with little to no bony stability…meaning it gains its stability primarily from soft tissue structures both inert (meniscus, ligaments) and contractile (quads, hammies, and a whole lot more).

Believe it or not, the knee actually has more evidence online than low back for its correlation of  posterior chain strength preventing injuries.

posterior chain strength preventing injuries.

A lot of the research is specific to ACL injury prevention, but honestly, mechanics resulting in various knee injuries are often similar to ACL mechanics.

One of the predisposing factors to knee injury is what is known as dynamic valgus (knee collapsing inward) mostly brought on by quad dominance.

The other major way it can be brought on is by lack of posterior-lateral hip control.

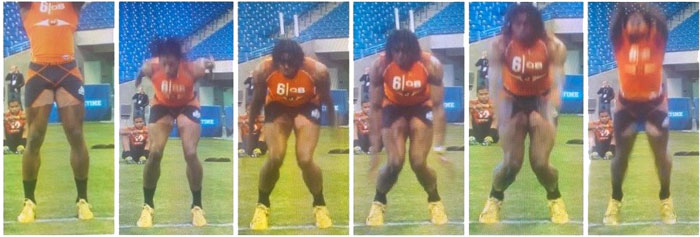

Most individuals are quad dominant because of sitting all day, turning off the glutes and hammies, and leaving the quads as primary movers. Here is a photo of one of my favorite examples of a dynamic valgus brought on by quad dominance (i.e. the quads winning the tug of war on the femur and pulling into dynamic valgus:

This is called “RG 3’ing.” Named after NFL Quarterback, Robert Griffin III.

Notice how his knees cave in as he develops power, this is a great example of when even “healthy” people can be predisposed to injury. Don’t RG 3….

How do we combat this? Well, this answer is multi-faceted, but Ill give you a hint… one of the best ways it to strengthen the posterior chain.

It’s really that simple.

There are TONS of ways to strengthen and target the posterior chain. As a matter of fact, just peruse Tony’s awesome website, and you will find tons of exercises… as I did when I was just a newbie in the S&C world.

Here are a few of my favorites:

1) Glute-centric: Bridging, every bridge variation….

2) Hamstring-centric: Nordic Hamstring curls (also AWESOME evidence for preventing hamstring strains)

Note From TG: This is an older video. So, relax internet trainer who doesn’t even perform this exercise in the first place, but is quick to point out how it’s not perfect technique. Am I bending a little too much from the waist? Yes. Is the music on point? Yes.

Here’s a nice regression:

3) Compound post chain: DEADLIFT, RDL, KB swings

Conclusion

You still need to train your anterior chain too! However, in a world where we’re stuck sitting for hours on end and prone to training our “mirror muscles,” placing more of a premium on the posterior chain is never a bad idea. For many reasons.

Anyone who might be interested in learning more and truly mastering the hip hinge, we will be hosting workshop July 24th at RX strength training in Medford, MA.

Either way, feel free to email me should you have any questions or anything about this you would like to discuss!

Peace, love, and glutes

About the Author

Dr. Zachary Gabor, PT, DPT, CSCS, USAW, is a 2015 graduate from Ithaca College where he earned his Doctorate of Physical Therapy.

Dr. Zachary Gabor, PT, DPT, CSCS, USAW, is a 2015 graduate from Ithaca College where he earned his Doctorate of Physical Therapy.