Back pain can be tricky. First off, anyone who’s ever dealt with it (pretty much everyone) knows it’s no fun. Second, there’s no overwhelming agreement as to what actually causes it. One person says weak glutes, another says tight hip flexors or hamstrings, and yet another may point to a bad hair day (NOTE: read this footnote, it’s a doozy —>).1

Third, if the stock photo I chose is any indication, back pain can also put a real damper on what can only be described as an Old Spice or Abercrombie & Fitch ad shoot.

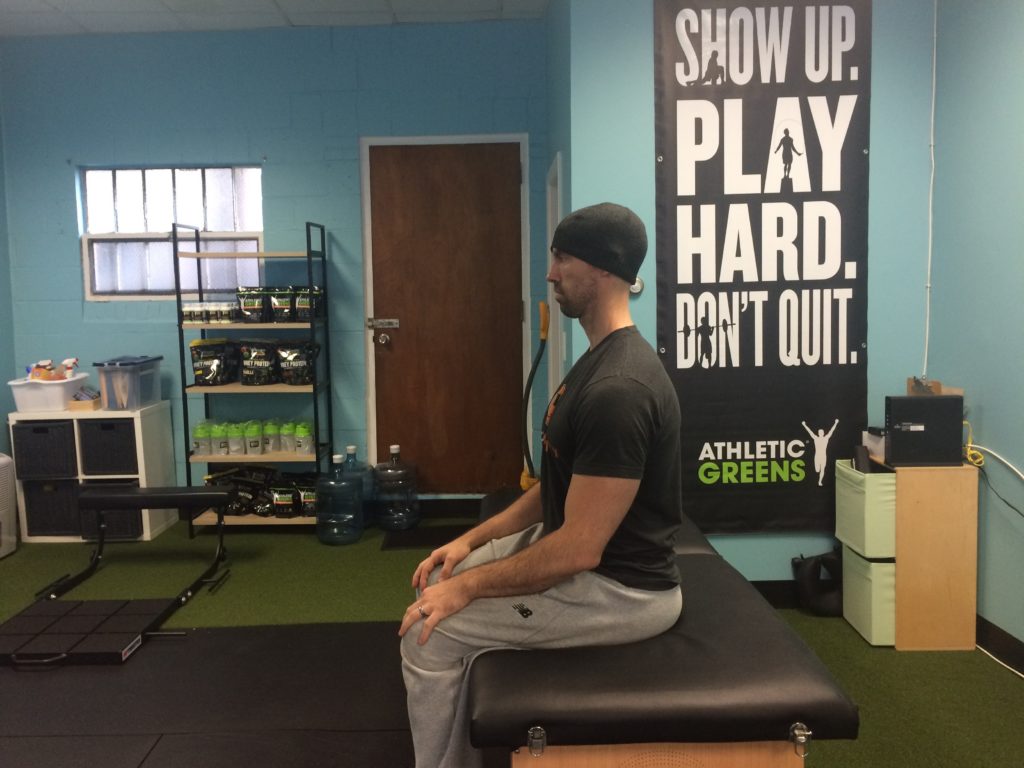

In my career as a personal trainer and strength coach I’ve worked with hundreds of athletes and clients battling low back pain. It comes with a territory as a fitness professional. I’ve tried my best to arm myself with the best skill-sets possible (within my scope of practice) to help my clients work through their low back shenanigans. I can assess – not diagnose – and try to come up with the best game plan possible to address things.

And, to be honest, addressing one’s lower back issues can be mind-numbingly simple.

In short:

“Find what movements hurt or exacerbate symptoms, don’t do those movements, and then find movements that allow for a degree of success or pain free training.”

I’d be remiss not to mention Dr. Stuart McGill’s work here. Not only is he one of the world’s Godfathers of spine research, but he’s also one of the world’s best mustache havers.

He’s co-authored hundreds of studies and written several books on the topic of low-back pain – with Ultimate Back Fitness & Performance (now in it’s 6th Edition) and Low Back Disorders being his flagship pieces of work.

Speaking of Ultimate Back Fitness & Performance, look who makes a cameo appearance on pg. 289 in the latest edition.

HINT: It’s a bald strength coach whose name rhymes with Macaroni Flentilzore

For the Record: TG Life Bucket List

Get to a point in my career where Dr. Stuart McGill not only knows who I am, but emails me out of the blue and asks permission to use a picture of me in his latest book update.- Appear in a Star Wars movie.

- Become BFFs with Matt Damon

My bedtime becomes 8 pm.

I’d have to say, however, that his most “user friendly” book is Back Mechanic. In it, he breaks down his entire method for “fixing” low back pain covering everything from spinal hygiene, assessment, corrective exercise, and strength training.

I’m not going to belabor anything, you can purchase the book and peel back the onion on his protocols (seriously, the assessment portion is gold).

I’ve noticed a trend in recent years, though. Dr. McGill has done so much for the industry and his work is so ingrained in our thoughts as fitness professionals that I feel the whole idea of “avoiding spinal flexion (sometimes at all costs)” has bitten us in the ass.

Yes, avoiding spinal flexion is a thing, especially if someone is symptomatic and flexion intolerant.2. It’s that point, though, “avoiding spinal flexion” that has gotten the best of us for the past decade or so.

We’ve done such an immaculate job at coaching people to know what “spinal neutral is” via prone planks, side planks, and birddogs, and then used strength training to engrain that motor pattern, that (some, not all) people transitioned into more extension-based back pain because they lost their ability to move their spine into (pain free) flexion.

Dr. Ryan DeBell discussed this phenomenon recently where he discussed his own back pain history. He started as flexion intolerant, trained himself into “spinal neutral,” (which is what you should do), started to avoid all flexion like an episode of Emily in Paris, and after awhile, extension-based movements & positions started to hurt…because he was locked into extension.

As a corollary, I see this quite often myself: someone comes in to see me and both flexion and extension based movements hurt. It’s so frustrating for the person and I can understand why.

My job, then, as the coach is to garner confidence and self-efficacy with my client/athlete and work with him/her on what I know tends to work….find movements that do not hurt and work from there.

Dr. McGill has his own version of the “Big 3,” or his go to exercises when first starting with a low-back person:

- The Curl-Up (I.e., not a sit-up)

- Side Bridge or Plank

- Birddog

Even when we master those movements, which are often very challenging for people when performed right, I’ll stick with them for a couple of weeks and just up the ante with appropriate progressions.

Lets take the birddog for example.

Birddog w/ RNT

The band adds an additional kinesthetic component where increased stiffness or engagement occurs in the anterior core and glutes. Truthfully, it’s not uncommon for me to START with this variation so the person can feel what their limbs are doing in space.

Birddog – Off Bench

Doing the birddog off the bench takes away a component of stability (feet off the floor) and forces people to slow the eff down and learn to control the movement. If they don’t, they fall of the bench. And I laugh.

Your Spine, Move It!

Going back to the assessment for a quick second, it’s not uncommon for me to assess someone and to find that their spine doesn’t move. Whether it’s because of a faulty pattern or they were coached to avoid flexion at all costs (even when asymptomatic) it’s as if their spine is Han Solo frozen in carbonite.

One screen I like to use is a the toe touch drill. When someone bends over to touch their toes there should be a consistent curvature/roundness of the spine. Often, what I’ll see is more of a “V” pattern where they’ll bend over, but instead of seeing a nice curve I’ll see their lower back stay flat throughout the movement; as in zero movement.

This can be just as detrimental as anything else. It may or may not be a root cause of their low-back pain, but I know it’s a red flag I’d like to address.

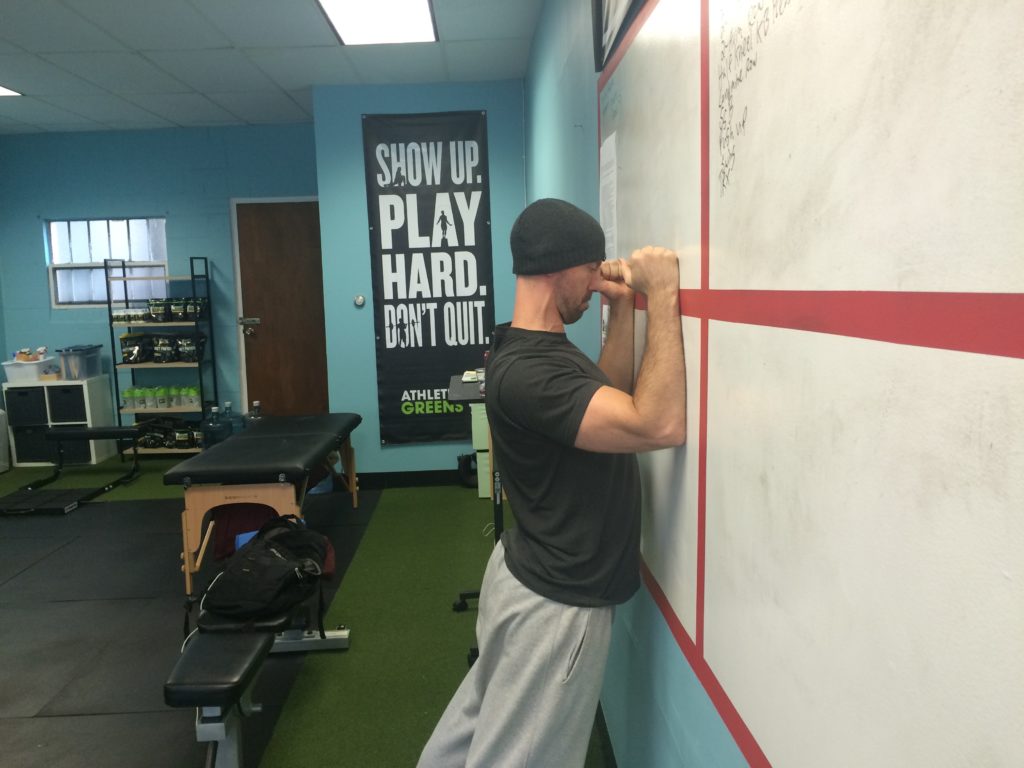

Segmental Cat-Cow

Below is a drill I’ve been using more and more with my low-back clients. We’re all familiar with the Cat-Cow exercise, where you round and arch your spine moving through a full-ROM.

Cool, great. The human body is great a compensating, and unless you have a keen eye for detail it’s easy to assume that if someone can round and arch their back they’re good to go. But

But are they? Often, if you SLOW PEOPLE DOWN it’ll become abundantly clear that they may move well in certain areas of their spine (thoracic), but not in others (often lumbar).

Coaching them through the movement – point by point, segmentally – is a fantastic way to hammer this point home and to help nudge them to move their spine in a slow and controlled fashion.

Give this one a try with some of your clients. COACH THEM. This drill doesn’t require more than two passes (up and down) per set, for a total of 3-4 sets. Helping them understand that they are allowed to move their spine – assuming it’s pain free – is a sure fire way to set them up for long-term healthy spine success.

Final Note (Because, #douchebagswillbedouchebags)

To appease the hoity toity internet warriors, couch coaches, and fitness influencers who have never coached an actual person (let alone a ham sandwich) out there. All of this DOES NOT insinuate that I am not ALSO using regular ol’ strength and conditioning to address things. All of the drills showcased above are just entry-level ideas or starting points.

I’m actually a massive fan of introducing unloaded rotational and/or spinal flexion/extension movements into the mix as well as loaded exercises such as Jefferson Curls to help build more resiliency within the spine and the musculature that supports it. In addition I’ll introduce things like tempo deadlift and squatting variations, various hip/low back dissociation exercises (I.e., other hinging alternatives), as well as a consortium of single leg exercises to help build overall strength.

As I always like to say…

You need to lift shit to fix shit.

It’s usually not a one or the other scenario. Both sides of the spectrum (motor control strategies and lifting heavy shit) need (and should) be considered.