One of the more flagrant “mic drops” I toss down whenever I speak to a group of fitness professionals (remember when we used to be able to do that in person?) is that forcing people to adopt a symmetrical stance while performing basic lifts such as deadlifts or squats is more likely hurting people rather than helping them.

In fact, I’ll go a step further and tell them symmetry in the human body doesn’t exist and then yell something like “UNICORNS ARE REAL!” and walk away.

You know, to keep people on their toes.

You’re Not Broken If You’re Asymmetrical. You’re Normal

We need to stop thinking we’re broken if we display any degree of asymmetry.

It’s 100% normal, actually.

The human body is designed asymmetrically. If it were so deleterious I think natural selection would have fixed it by now don’t ya think?

Admittedly, I appreciate it’s a tough nugget to swallow…the whole “symmetry is a myth” thing.

I had a hard time tackling it myself. For years all I read was how we should strive for perfect balance and symmetry both statically (posture) and dynamically (think: maintaining a symmetrical stance during a set of squats).

However, the more I worked with people – with varying backgrounds, injury histories, and body-types – and the more I coached, the more I realized it was all B.S. Holding everyone to the same standard didn’t make sense.

The tipping point for me was my introduction to PRI (Postural Restoration Institute ®) a number of years back. Neil Rampe stopped by Cressey Sports Performance and did a 1-day workshop and opened my eyes to just how UN-symmetrical the body really is.

As noted above, it’s designed that way, in fact.

It helps us.

This was pretty much reaction

Not long after Michael Mullin stopped by CSP several times and took the entire staff through a number of in-services which further slapped me in the face with the whole Morpheus “blue pill/rep pill, we’re asymmetrical creatures, open your eyes” schtick.

More currently, guys like Dean Somerset, Dr. Ryan DeBell, Dr. John Rusin, Dr. Stuart McGill, and Papa Smurf agree: The human body is all sorts of effed up.

But in a good way.

In some facets of life symmetry is the goal.

A ballet dancer needs to elicit “symmetry” when performing, as does a figure athlete or competitive bodybuilder when strutting their stuff on stage. No one ever won Ms. Olympia or Mr. East Lansing Stud Muffin with a yoked up right quadricep and a teeny tiny left.

But those examples aren’t necessarily the same thing as what I’m referring to in this post. Aesthetically, symmetry is visually pleasing.

90’s Mariah = pleasing

Crazy Eyes from Mr. Deeds = not pleasing

However, for performance or function, symmetry shouldn’t necessarily be the default goal or expectation.

It’s a hefty statement to make, and whenever I say something so seemingly egregious it often invokes a little push-back.

“Well, what about cars?” someone may blurt out. “If we don’t maintain alignment (symmetry) the car will start veering to one side or the other, causing additional wear and tear on the tires, and run the risk of further damage.”

To this point, I agree. Cars are designed by engineers and manufactured by computers and machines with precise precision to be replicated over and over and over again to (hopefully) ensure a quality product and return business from consumers.

The human body is not a Volvo.

This isn’t to insinuate the human form is any less fantastical, beautiful, intricate, or complex of a design. But, you know, we’re not some Clone Army to be replicated en mass.

Dare I say: This is a rare moment where “we are, indeed, all special snowflakes.”

During our Complete Shoulder & Hip Blueprint (dates are in the works for a return in early 2022!), Dean Somerset and I try to reiterate to attendees that asymmetries are normal and that, often, we’re doing a disservice to our clients and athletes by forcing them all into a standard, one-size-fits-all way of doing things.

It’s important to recognize everyone has variances in bony structure.

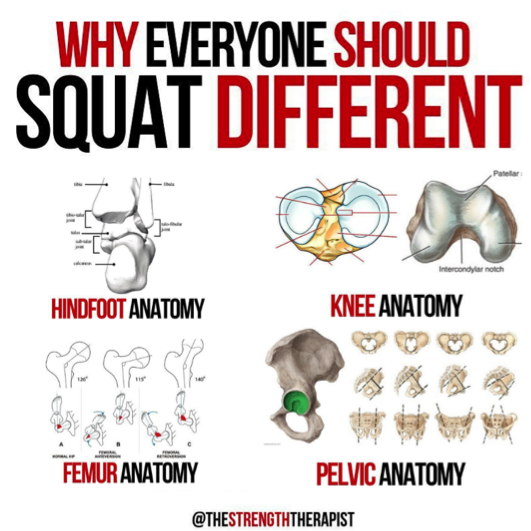

Using the hips as an example we know:

- Pelvic structures differ person to person.

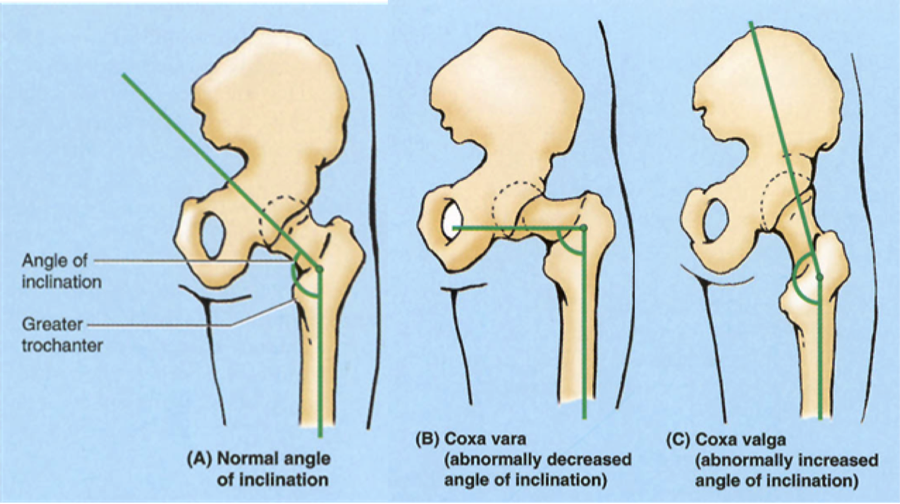

- Femoral angles vary person to person.

- Hip socket depth can vary (Scottish hip)

- People have two hips (surprise!) and either side can have retroverted or anteverted acetabulums, as well as retroverted or anteverted femoral heads. All of which affects someone’s ability to flex, extend, abduct, adduct, externally and internally rotate the joint.

To that end, when coaching someone up on the squat why not use those variances to better set up your clients and athletes for success?

Much like what an optometrist does when fitting someone for a new pair of glasses, sitting someone down in front of that thingamabobber (<— I believe that’s the technical term) and flipping back and forth between lenses to see which looks and feels better – is this better, or is this? – why is the parallel approach all of a sudden wrong when trying to figure out the best squat stance for someone?

Shouldn’t it be our goal to figure out what stance feels more stable, powerful, and balanced? I’d make the case we’re trying to fit square pegs into round holes much of the time when we force people to use a symmetrical stance.

Why?

Especially when we know there’s a multitude of structural anatomical variance from person to person.

But, How Do We Tell?

If you’ve somehow developed a mutant power of X-ray vision:

1) That’ll help

2) Can we hang out?

Performing a thorough assessment – something both Dean and I cover in depth HERE (hint, hint) – will provide a ton of feedback and help peel back the onion of what will be the right approach for someone.

You could also watch Dr. McGill take someone through a hip scour here:

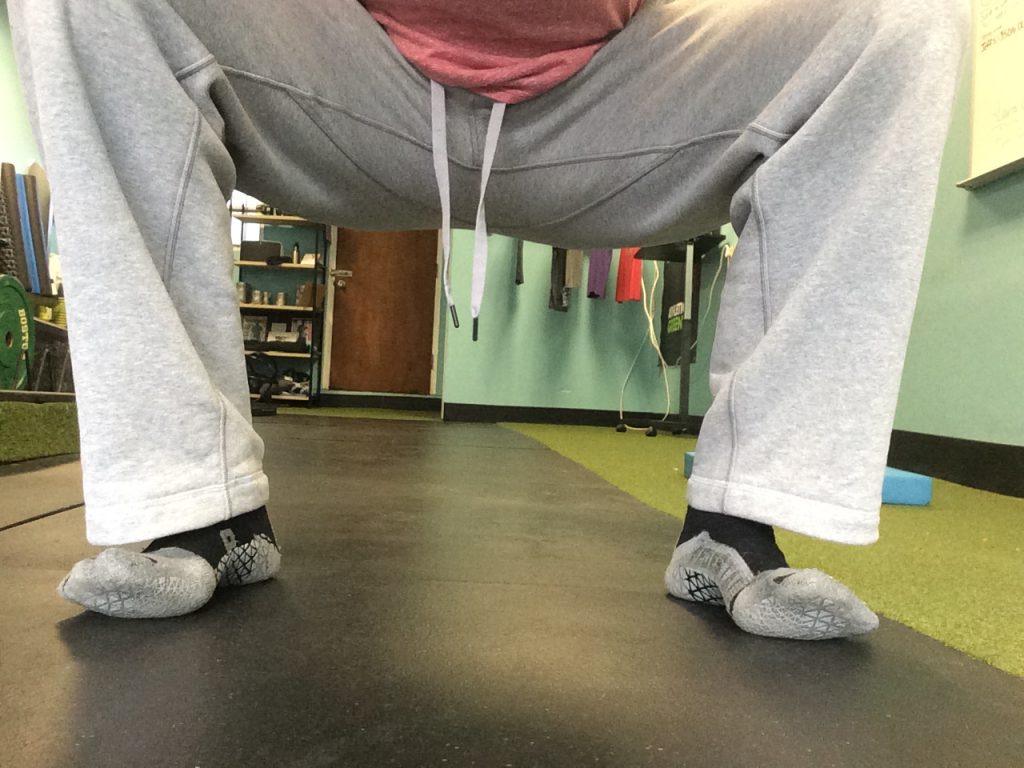

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve encouraged someone to use a staggered stance when squatting, or maybe to externally rotate one foot more than the other, and then they perform a few repetitions and they look up and say “holy shit-balls that feels so much better.”

And we hug.

Why would I disregard that?

We’re not causing irreparable harm by accepting asymmetry.

We’re just accepting people’s differences.