The topic of low back pain (LBP) – how to assess it, diagnose it, and how to treat it – can be a controversial one. I italicized the word “can” because I don’t feel it’s all that controversial.

Cauliflower as an option for pizza crust or Zach being chosen as the bachelor on the current season of The Bachelor (when it’s 100% clear that a ham sandwich has more charisma) = controversial.

Simple stuff to consider to help with one’s LBP = not so much.

Everything and Nothing Causes Low Back Pain

The topic of low back pain and how to address it is controversial because there’s no one clear approach or answer to solve it.

(And if the last 3+ years of this pandemic dumpster fire has taught us anything it’s that we looooooove to argue over what’s best and what works).

SPOILER ALERT: Everything and nothing causes LBP.

Have ten different doctors or physical therapists work with the same patient and it’s likely you’ll get ten different opinions as to what the root cause is and what tactics need to be implemented to resolve it.

One person says it’s due to delayed firing of the Transverse Abdominus (TA), while someone else states it’s due to someone’s less than great posture or tight hamstrings.

For the record, all are weak excuses at best.

The culprit can rarely be attributed to any ONE thing.

But it’s amazing how often “tight hamstrings” is the fall guy.

- Low back pain? Tight hamstrings.

- Knee hurts? Tight hamstrings.

- Have Type II Diabetes? Tight hamstrings.

- Brown patches on your front lawn? Hamstrings.

It’s uncanny.

I mean, I could just as easily sit here and say in worse case scenarios LBP results from drinking too much coffee. I have zero evidence to back that up, but whatever.

…neither do most of the other “culprits” people tend to use as scapegoats.

So, why not coffee?

Or Care Bears for that matter, those sadistic fucks.

What works for one person, may exacerbate symptoms for someone else. And as my good friend, Dr. John Rusin notes:

“Fact of the matter is: there is NO one right way. it’s a big mistake to lump all LBP into the same category and even a bigger mistake to assume all of it presents the same or should be treated the same.”

There’s no way for me to write a thorough blog post on such a loaded topic; especially one that will make everyone happy.

It’s impossible.

I have better odds at surviving a cage match with an Uruk-hai.

Part of me feels like the proper response to the question “what causes low back pain and what’s the best way to address it?” is this:

But that would be woefully uncouth of me.1

Most people reading aren’t clinicians or physical therapists. There’s very little (if any) diagnosing going on in the hands of a personal trainer or strength coach. And, truth be told, if you are a personal trainer or strength coach and you are diagnosing, YOU……NEED…….TO…….STOP.

Just stop.

It’s imperative to defer to your network of more qualified (and vetted) fitness/health professionals whom you trust to do that.

However, it’s important to also consider we (as in personal trainers and strength coaches) are often the “first line of entry” into the medical model. We’re the first to recognize faulty movement patterns, weakness, imbalances, and bear the brunt of questioning from our clients and athletes when they come to us with low back pain.

There’s quite a bit we can do to help people.

What follows is a brief look into my mind and what has worked for me in the past with regards to LBP; a Cliff Notes “big rock” brain dump if you will.

Sorry if I offended anyone who likes Care Bears.

1) Rest Is Lame

My #1 pet peeve (and many agree with me) is that “rest” is the worst piece of advice ever.

“Go stick your finger in that electrical socket over there” would be better.

This isn’t to say there aren’t extenuating circumstances where taking a chill pill is absolutely the right choice; sometimes we do need to back off and allow the body a window of time to heal or reduce pain/swelling/symptoms.

That said, I think it’s lame when a medical professional tells someone to “rest,” or worse, informs them that they’ll need to learn to “live with low back pain.”

It’s a defeatist attitude and will spell game over for many people. Before you know it they’re living on a foam roller and thinking about a “neutral spine” while washing their hands.

(NOTE: I am not anti-teaching neutral spine to people. It’s a lovely starting point for most people, but at some stage people need to learn to move in (and out) of precarious positions…because that’s life).

A common theme reverberated in the S&C community is to say “strength is corrective.” I wholeheartedly agree with this sentiment. In fact, why the hell has this not been made into a t-shirt yet?

However, I think a slightly better moniker may be to say:

“Movement is corrective.“

We can use movement (and yes, strength) to help people get out of pain. Rest has its time and place, but I find stagnation to be more of a problem.

The body is meant to move and is wonderfully adaptive. And that’s the thing: adaptation and forcing the body to react to (appropriate levels of) change and stress is paramount to long-term success with LBP.

Sitting on a couch watching Divorce Court in the middle of the day isn’t going to help.

2) Move, But Move Well

I was watching Optimizing Movement with Mike Reinold recently and he noted there are three key elements to movement and why someone may not do it well:

- Structural Issues

- Coaching/Technique

- Programming

It’s important to understand that, in this case, everyone is a unique snowflake.

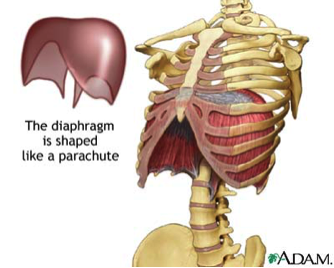

Structure: Anatomically speaking there is huge variance amongst the population. Hip structure, for example, can have a large effect on someone’s ability to squat to a certain depth or get into certain positions. Likewise, who’s to say the hips are always the culprit? Even upper extremity considerations – like one’s ability to bring their arms overhead (lack of shoulder flexion) – can have dire consequences on back health.

The body likes to use the path of least resistance (also the most efficient) to accomplish any task. However in this case, “most efficient” doesn’t mean best. As Reinold notes:

“Efficient in this case refers to energy, not movement.”

Lack of shoulder flexion will often lead to compensation via more extension through the lumbar spine. It’s efficient movement, but it’s not better movement.

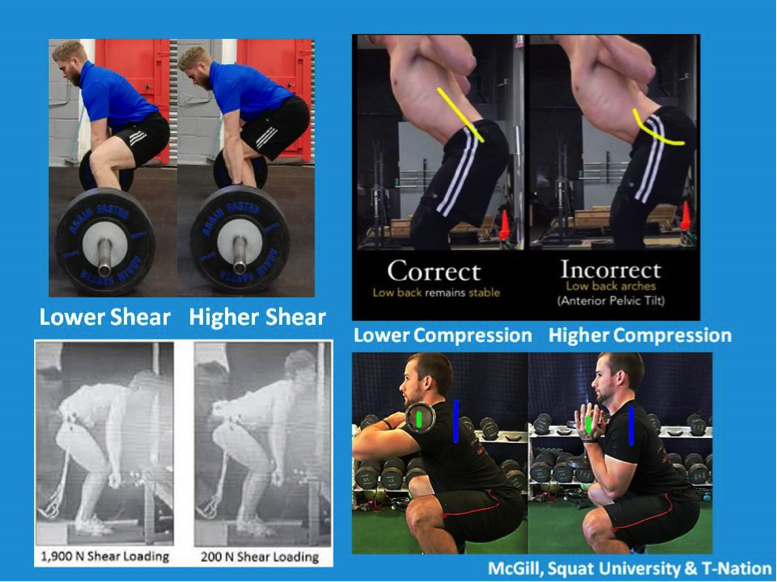

Coaching/Technique: I’m a firm believer that everyone should deadlift (it’s a hip hinge, learning to dissociate hip movement from lumbar movement, doesn’t mean we have to load it), but I don’t feel everyone should do it from the floor or with a straight bar.

Cater the exercise to the lifter, not the lifter to the exercise.

Programming: If someone lacks hip flexion why have them conventional deadlift? If someone lacks shoulder flexion why have them perform overhead pressing or kipping pull-ups? Some of the onus is on YOU, dear fitness professional.

Hell, even something as simple as how you coach a plain ol’ vanilla Prone Bridge/Plank can shed some light here.

What’s the point if the end result looks like this?

Which brings us to another golden rule.

3) Finding Spinal Neutral (Pain Free ROM) is Kinda Important

In light of a past gem by Dean Somerset on what the term “spinal neutral” even means, I realize this comes with a bit of grain of salt.

I just want to find a pain-free ROM and to help people with low back pain to own that ROM.

It’s the McGill Method 101.

Find what actions hurt or exacerbate symptoms, and stop doing it.

I know I just blew your mind right there.

For example:

1. Client says “x” hurts, and then places their body into some pretzel like contortionist position that would make a Cirque du Soliel performer give them a high-five.

Me: “Um, stop doing that.”

2. But that could also mean addressing how they walk or how they sit in a chair. Someone with flexion-based back pain, will like to be in flexion, a lot.

Maybe taking them through a slump test will offer some pertinent info.

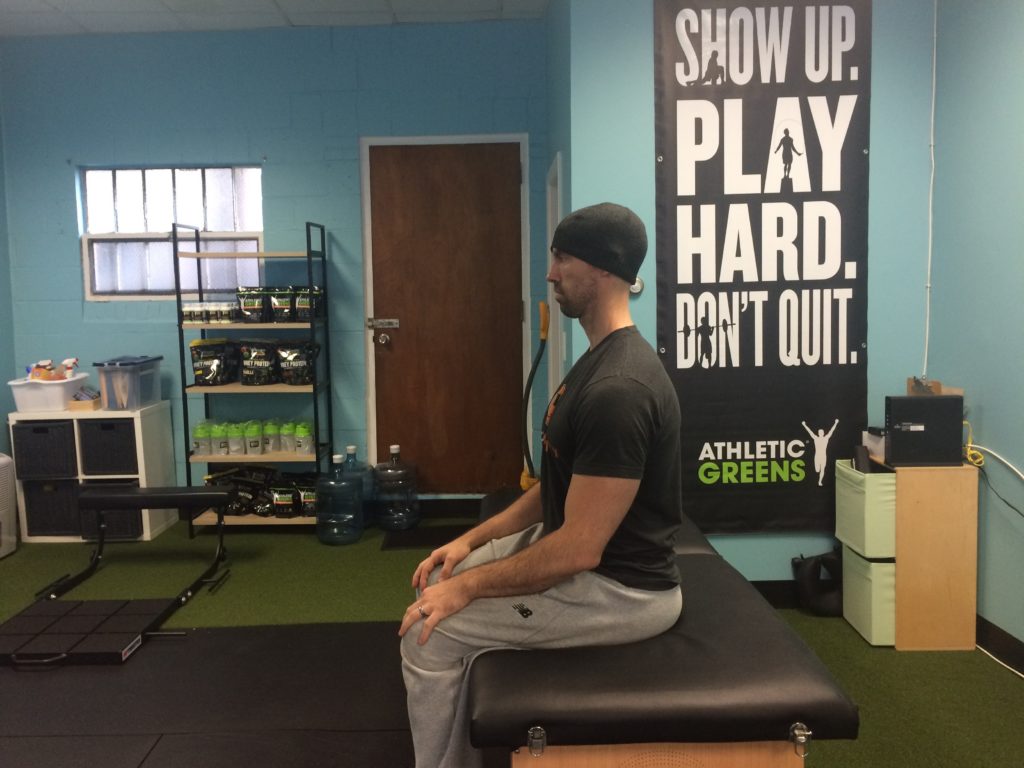

Have them start in a “good” position:

Then, have them purposely “slump” into excessive flexion:

Someone who is flexion intolerant – despite preferring to be in that position – will often say this causes pain.

Ding, ding, ding.

So, the “fix” is to coach them up and try to keep them out of excessive spinal flexion. Cueing them how to sit in their chair and to get up (wider base of support, brace abs, chest up), building spinal endurance (and strength) via planks, and having them hang out in more extension may be the right path to take.

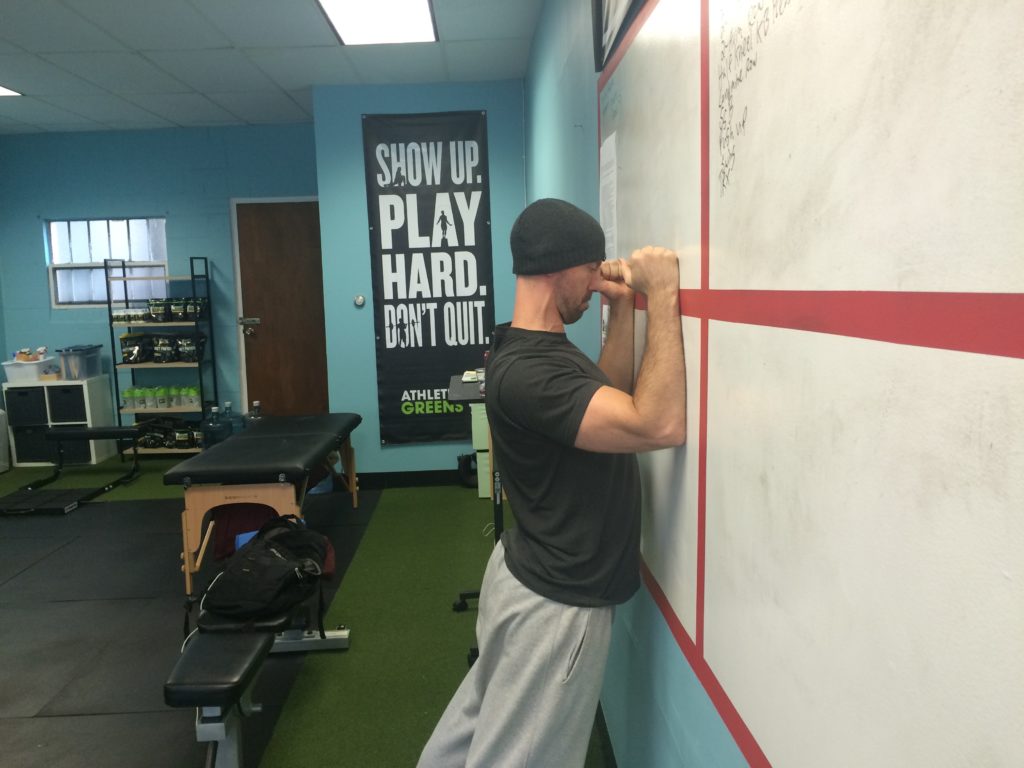

3. On the opposite side of the spectrum is extension, which is often a problem in more athletic populations and in those occupations requiring more standing (ahem: personal trainers/coaches).

Here you might put them into extension and see what happens.

Much like people who are flexion intolerant “liking” flexion, those in excessive extension will like to live in extension.

This will likely hurt.

Finding their spinal neutral is key too.

Hammering spinal endurance/strength via planks (done well) still hits the nail on the head, as does nudging them towards exercises that emphasize posterior pelvic tilt (much of time cuing people NOT to excessively arch during their set up on squats and deadlifts), and even drills that promote spinal flexion…albeit unloaded.

Spinal flexion doesn’t always have to be avoided. In fact, it’s sometimes needed.

Either way, meticulous attention to detail on finding spinal neutral – or pain from ROM – is huge. Once that is addressed, and symptoms has subsided, we can then encourage them to marinate in more amplitude of movement, taking them OUT of spine neutral (cause, it’s gonna happen in everyday life) and use the weight-room to help strengthen those new ROMs.

But I digress.

4) Don’t Treat People Like a Patient

I know this will rub some people the wrong way, but I still use the deadlift for the bulk of people I work with you have LBP.

Nothing sounds so absurd to me than when I hear someone say how the deadlift is ruining everyone’s spines.

To recap:

Deadlift = hip hinge.

Hip Hinge = learning to dissociate hip movement from lumbar movement.

Mic drop.

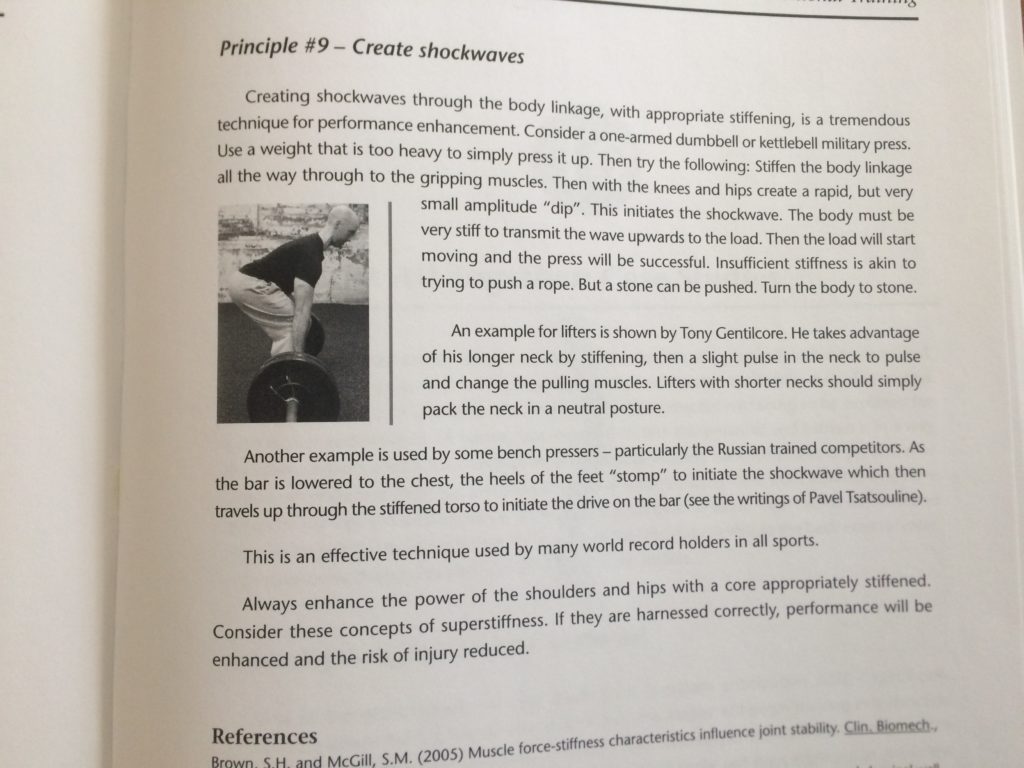

Resiliency is key in my book. And not many movements make the body more resilient than the deadlift or any properly progressed hip hinge exercise catered to the individual’s goals, injury history, and ability level:

Assuming I have coached someone up enough to understand spinal neutral and they’re able to maintain it, why not poke the bear and challenge them?

A deadlift doesn’t always mean using a straight bar and pulling heavy from the floor until someone shit’s their spleen.

I can use a kettlebell and band to groove the movement:

I can also use a trap bar, which is a more user-friendly way of deadlifting as it allows those with mobility restrictions to get into a better position compared to a straight bar.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p-sA3PG1kGY

Too, I have found great success with various other exercises:

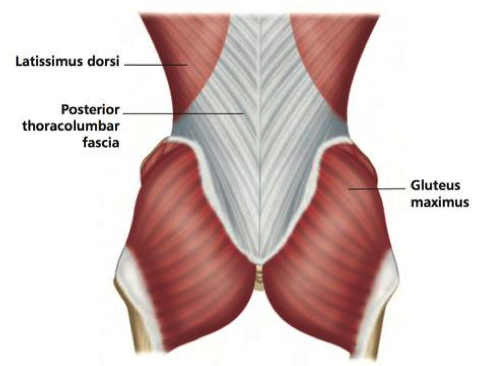

- Farmer and Suitcase carries

- Shovel Holds

- “Offset” loaded exercises like 1-arm DB presses or 1-arm rows, lunges or RDLs (where you hold ONE DB to the side and perform the exercise). It’s a great way to increase the challenge to the core musculature.

- Or even outside-the-box exercises like Slideboard Miyagi’s

So long as we’re staying out of precarious positions or those positions which feed into the issue(s) at hand, we’re good.

Find a training effect with your clients/athletes.

Help them find their TRAINABLE MENU.

And That’s That

People have low back pain for a variety of reasons: They’re too tight, too loose, too weak, have poor kinesthetic awareness, or they’re left handed.

The umbrella theme to remember is that there is never ONE root cause or ONE definitive approach to address it across the board. However, that doesn’t mean there aren’t some “big rock” things to consider that will vastly improve your’s and their chances of success.

I hope this helped.

And, again, sorry about the Care Bear comment.

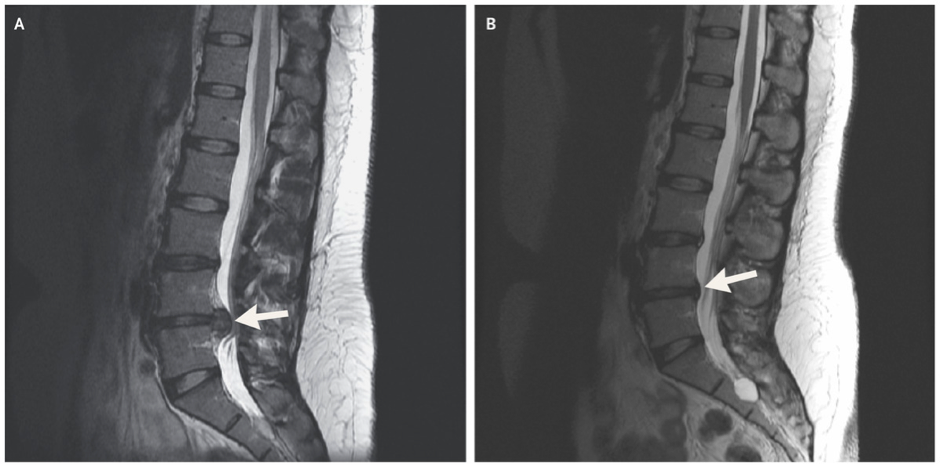

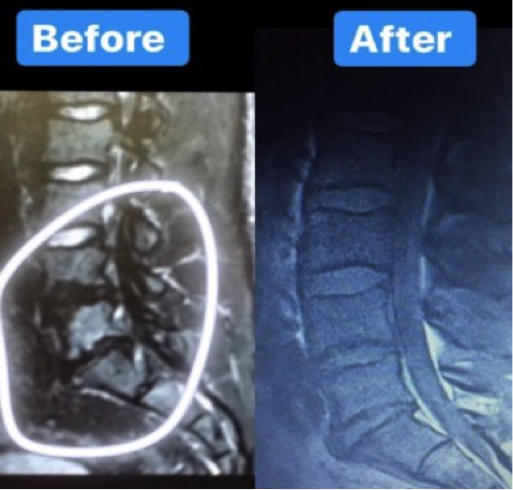

After rupturing my L5-S1 disk over 7 years ago I was told that surgery and pain meds were my only option for a “pain-free” life.

After rupturing my L5-S1 disk over 7 years ago I was told that surgery and pain meds were my only option for a “pain-free” life.