Note From TG: I apologize in advance for the “click-bait” nature of this article. I have to assume that, based off the title, many of you have travelled a long distance across the internet to read what follows.

Welcome.

I hope you stick around. This is a guest post from strength coach, Travis Hansen. Do I agree with every word? No. Do I feel he brings up many valid points? Absolutely.

And on that note, happy reading.

Without a shadow of a doubt, the question that I get asked more than any other as a coach, goes something like this: “Is your training style like CrossFit?”

Rather than get upset or start verbally bashing CrossFit like many do, I just simply inform the person that our training system is different in that it’s “athletic based” and CrossFit simply is not. But wait, Crossfitters are tremendous athletes right?

Unfortunately, they aren’t and by the end of this article you will know exactly why.

Copyright: tonobalaguer / 123RF Stock Photo

Now if you have an extreme bias and preconceived notion regarding the CrossFit training philosophy, please try to stay objective and hear me out. I promise to stay completely objective even though it may come off harsh, and I will provide you with the facts for why we can’t and shouldn’t refer to Crossfitters as great athletes.

Athletic = CrossFit?

Lets begin with the actual definition of being athletic. What does it mean, who has it, and who doesn’t? Automatically, it is safe to say that we would associate this term with people like Calvin Johnson, Lebron James, Mike Trout, Yasiel Puig, Michael Jordan, Russell Westbrook, Serena Williams, and many more.

And we definitely should since these individuals undoubtedly epitomize athleticism. The definition of being athletic is the capacity to perform a specific skill set or series of skills at a high level to help improve sport performance. Below is a list of the predominant athletic based skills.

Athleticism:

Power

Strength

Speed

Agility and Quickness

Conditioning

Now if a person can perform each of these at an ultra-high level they are going to be insane on the field, court, or wherever more times than not. Why? Because he or she will be able to express any specific sport skill, and research has shown that sport skill attainment is enhanced with increased athletic ability.

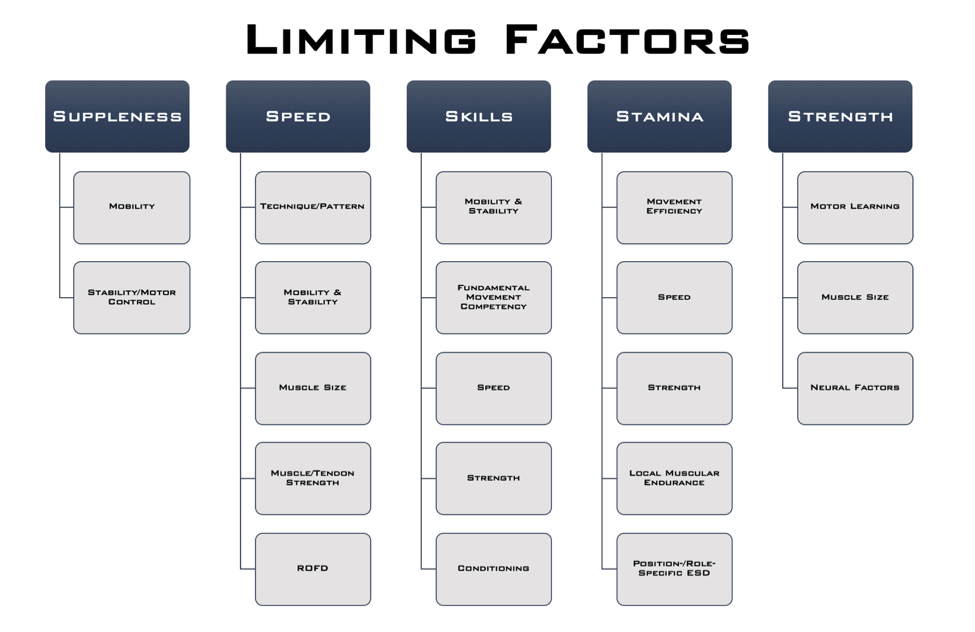

Next, I would like to also include some areas of training that serve as secondary and will help regulate performance in the athletic skill set. I will just call these secondary factors.

Secondary Factors:

Nutrition

Prehab-Rehab

Program Design

Muscle Building

Fat Loss

So taking into account just shear athletic skill, how should we rank CrossFit? I scored the system a 1 out of 5 or 20%. In other words it fails miserably for an actual athlete looking to perform better in a specific sport setting.

Copyright: ammentorp / 123RF Stock Photo

Words and opinion are very cheap, so I will show from a scientific and evidence based standpoint why they receive such a low score. Afterwards, I will elaborate on how crossfit fares with the support areas known as secondary factors, and finish by addressing any other areas of athletic development in which you didn’t see listed and how they fall into the puzzle.

Are You Still Reading?

The first skill on the list that we need to tackle is power. What is power? Power by definition is Force x Velocity. I like Strength x Speed which essentially means the same thing and is a bit easier to understand for most.

So it’s the ability to express as much force as possible as fast as humanly possible. Common displays or formal assessments for power that we use as athletic development or strength and conditioning coaches that you commonly witness in the sport realm is the Vertical Jump, Broad Jump, Running Vertical Jump, Throwing Velocity, Hang Clean/Snatch, etc.

Now how many people in CrossFit do you see perform a standing 40” Vertical Jump? How many do you see perform a 45-50” Running Vertical Jump? How about a 10’+ Broad Jump? Or a PROPERLY performed Hang Clean executed with a load that is 1-1.5 times that person’s bodyweight?

Before I continue, please don’t go out and scour the web desperately in an attempt to locate one individual who attained some of these values and had to have been practicing CrossFit at the time.

There are exceptions to every rule.

What’s important to note is that the system as a whole doesn’t come close to implementing the methods necessary to elicit these types of performances on a regular basis like so many athletic training systems across the country do. Keep in mind that these figures have become commonplace in team sport settings and scale MUCH MUCH higher in the elite population of athletes.

The next skill on the list is Strength. The ability of a muscle or muscle group to produce maximum voluntary force without time being a factor. A population that demonstrates this better than any other on the planet should immediately come to mind, and this is Powerlifters!

[Also, any athlete looking to become more athletic should adopt and perform a modified version of a powerlifting system such as Westside Barbell to maximize their athleticism.]

Lets stay on the topic at hand though. How does CrossFit as a whole score in the strength training department? Unfortunately, not very well at all. Without providing personal observations of this, I would way rather provide you with some valid “Strength Standard Charts” to reference as sound evidence HERE:

Now taking into account this solid reference which has factored in a legion of lifters across various federations at different body-weights, how would CrossFit score?

Not very good.

How many of these individuals do you know that can Bench Press 1.5-2x their bodyweight, or Squat and Deadlift 2.5-3x their bodyweight following a CrossFit training system? Not very many if you are being honest.

Ok this next one should not take too long. Speed! How many people in CrossFit do you know who can record an electronic 2.5-2.6 second 20 yard dash, or a 4-2-4.4 second 40 yard dash, or a sub 6.7 second 60 yard dash? Few and far between.

Agility and Quickness are next on the athleticism list. Also known as “Change of Direction Training” in many sectors, Agility and Quickness is the ability to accelerate and begin rapid motion in one direction, decelerate in that same direction, plant properly and then re-accelerate or “cut” in a new direction fast!

Exercises such as the 5-10-5, Cone Drill, 1-2 Stick Series, etc. are great variations that serve as Agility and Quickness Training Tests.

Note From TG: it kinda-sorta looks like this…..;o)

Moreover, guys like Barry Sanders and Darren Sproles are brilliant examples of this athletic skill at work. If you really watch it’s not very hard to identify that just the shear nature of CrossFit fails to deliver here.

Team sports such as football, basketball, baseball, soccer, hockey, lacrosse, etc. are so athletic and require that a male or female constantly move and react in all 3 planes of motion as fast as possible through the entire muscle contraction spectrum (concentric, eccentric, and isometric). CrossFit on the other hand lives on a tightrope as events are practiced in an exclusive linear fashion, omitting an essential athletic quality.

As I’ve visited different “boxes” just mainly out of curiosity, or heard Crossfitters brag to me about how athletic they were, I’ve never actually seen drills practiced that encourage the development of this athletic function. Have you? Therefore it’s only fair to discount this system as an option for enhancing Agility and Quickness.

Conditioning is obviously going to be the one area of performance where I would have to credit CrossFit absolutely.

Several Crossfitters possess tremendous work capacities and development of the 3 metabolic energy systems (Alactic, Lactic, and Aerobic) much like boxers and MMA fighters. This can be seen at any of the CrossFit Games on ESPN. In regards to strictly conditioning, the feats exhibited by these competitors is quite impressive.

What Next?

So as of right now I believe I’ve proven to you why CrossFit fails in terms of effectively enhancing athleticism. Next I think it’s important to briefly analyze all secondary measures which could impact the primary skills to show what else may or may not be missing for athletes looking to get more athletic and better in a particular sport, who regularly practice CrossFit.

The first element that I would like to discuss is Nutrition. Obviously, “The Paleo Diet” is the foundation for all of the CrossFit population. I must admit that I think there were quite a few positives I took away from both books. The intent of the content is very health-based, the food selection is very nutrient dense, and Dr. Loren Cordain disclosed some interesting scientific points surrounding the topic for sure.

In his book “The Paleo Diet for Athletes,” Dr. Cordain does a great job of adjusting the modern Paleo diet recommendations and states the need that athletes following the Paleo Diet could derive half of their total caloric intake for the day from healthy carbohydrate sources:

“For example, an athlete training once a day for 90 minutes may burn 600 calories from carbohydrates during exercise and needs to take in at least that much during stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 of recovery. This athlete may be eating around 3,000 total calories daily. If he gets 50 percent of his daily calories from carbohydrate, he would take in an additional 900 calories in carbs that day in stage 4, above and beyond the carbohydrate consumed in the earlier stages of the day.”1

And if you would like to know exactly why athletes need more carbohydrates than check out this series of articles I recently wrote:

5 Scientific Reasons to Eat Carbs

5 More Scientific Reasons Athletes Should Eat Carbs

Even More Reasons Why Athletes Should Eat Carbs

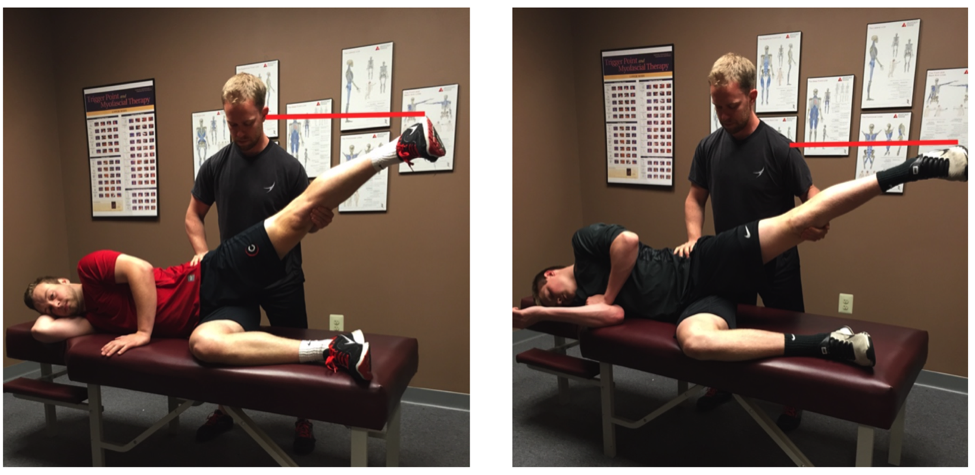

Prehab and Rehab Techniques are critical for competitive athletes who want to excel indefinitely, and it should be categorized as its own type of training if it officially is not already.

Techniques such as immersion baths, contrast, EMS, massage, tempo work, mobility/bodyweight circuits, meditation-relaxation, cat naps, static stretching, corrective exercises, and much more have been scientifically proven to hasten recovery from all the high intensity work and provide several benefits (Blood flow, nutrient and hormonal delivery, etc. etc.) to ultimately assist in athletic enhancement.

A majority of this should be implemented into a competitive athlete’s program from the get go, however, I’ve never really seen much discussion or emphasis of this type of training from Crossfitters, so I can only assume it’s not very important to this culture even though it’s undoubtedly essential to athletic performance.

Without a properly structured training program it would be very difficult to ensure that athlete’s are staying healthy and improving in all facets of performance over the long-term. Periodization is key and serves as the foundation for everything in the program.

However, I’ve never officially heard of any type of scientifically valid program design model being implemented for athletes who follow CrossFit. Do you guys elect a Linear, Alternating, Undulating, Concurrent, or Conjugate based System?

What I do know is that the works of famous programming researchers such as Tudor Bompa, Charlie Francis, and several others have shown us that having a pre-planned annual training model is a must for an athlete looking to reach his full potential. 2

A simple “WOD” which is arbitrarily designed to satisfy that particular day’s workout in the name of a male or female, will not suffice and the results will show.

Note From TG: here’s where I’ll chime in. The idea that all CrossFit boxes don’t adopt some semblance of programming structure is a bit harsh (not that I think that’s what Travis is implying). I’ve trained at and observed numerous CrossFit gyms and have been very impressed with numerous staff’s and their attention to detail on this topic.

To say that Ben Bergeron – who coached both winners (male and female) at this year’s CrossFit Games – doesn’t implement a “plan” or pay special attention to detail with regards to how to best set up/periodize his athletes for success is unrealistic.

Just wanted to give some props when props is due.

The last two remaining secondary factors are fat loss and muscle building qualities.

I must give kudos to CrossFit for creating a lot of fat loss testimony all over the world. I’m sure that thousands of people have lost weight/fat utilizing the CrossFit system. 3

However, what really bugs me is that you rarely if ever hear credit being distributed by CrossFit authorities on where specific training strategies were adopted. Did they just magically guess and innovate methods proven to work better than anything on the training market?

Hell no.

Furthermore, I see many specialized fat loss techniques being regularly implemented by CrossFit such as: HIIT, Metabolic Resistance Training, Timed Sets, Complexes, etc. but where the hell did that come from?

Not Crossfit unfortunately.

Ten years ago a guy by the name of Alwyn Cosgrove was busting out fat loss manuals left and right and disclosing drills and methods I nor anyone had ever seen before. The training concepts were brilliant and revolutionary at the time, but still hadn’t hit the mainstream yet. He was also sending out newsletters at the time which validated these now popular methods through sound research and tremendous data he was collecting at his training facility in South California with his wife Rachel, who was also a proven expert. I still have them. But how many of you actually know Alwyn and Rachel Cosgrove? I guarantee not as many as there should be.

Muscle Building is the final remaining topic that needs to be discussed. It’s no secret now that the CrossFit system involves primarily a moderate intensity/high training volume approach for general fitness, conditioning, and fat loss purposes.

With that being said this form of training environment will lend well to acquiring quality muscle mass pretty fast and it’s also why so many of the guys that practice CrossFit are pretty jacked. If you want to know more in depth info on this topic then definitely checkout the research and works of guys like Jason Ferruggia, Brad Schoenfeld, Bret Contreras, and Lyle McDonald.

Specific muscle mass or cross sectional area is also going to be a very strong indicator of athletic success in many cases, so this is one area where CrossFit has a decent foundation laid out if they can implement all of the training concerns mentioned previously.

Inter and Intramuscular Coordination, balance and stability training, and core training are I’m sure other areas that coaches or anyone reading this would think needs to be a primary concern. Fortunately, the methods employed for the primary skill set I provided you will do a tremendous job of enhancing these qualities indirectly. Here is a piece I wrote for the ISSA awhile back which illustrates my point as it pertains to balance-stabilization training:

Does Balance Training Improve Speed?

Well That’s it Everyone.

I hope you enjoyed this piece and learned the distinction between CrossFit and real athletic training.

They are presently very dissimilar, although they get tied in together many times based on my experience for whatever reason. Too re-iterate I’m really not trying to demean or be destructive towards the CrossFit philosophy at all. Peer review should be overly critical and brutally honest. I’ve written many articles and a couple of books and I can tell you firsthand that this is the case from the experts that analyzed my work, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.

If CrossFit is really serious about crossing over into the athletic training realm, then they need to start taking science more seriously, credit the founders, and utilize methods that are actually intended for athletes that truly work.

Lastly, I really think we currently underrate just how great so many high level team sport athletes really are. Genes aside, contemporary team sport athletes are amazing. On a final note, understand that athletic development is a big puzzle, and there is a lot that has to come together for any one athlete to be successful.

SCIENTIFIC REFERENCES:

#1-Cordain, Loren. The Paleo Diet for Athletes. Rodale. Emmaus, PA. 2005.

#2-http://articles.elitefts.com/training-articles/sports-training/overview-of-periodization-methods-for-resistance-training/

#3-http://www.bjgaddour.com/what-do-you-think-about-crossfit

About the Author

Travis Hansen has been involved in the field of Human Performance Enhancement for nearly a decade. He graduated with a Bachelor’s degree in Fitness and Wellness, and holds 3 different training certifications from the ISSA, NASM, and NCSF. He was the Head Strength and Conditioning Coach for the Reno Bighorns of the NBADL for their 2010 season, and he is currently the Director of The Reno Speed School inside the South Reno Athletic Club. He has worked with hundreds of athletes from almost all sports, ranging from the youth to professional ranks. He is the author of the hot selling “Speed Encyclopedia,” and he is also the leading authority on speed development for the International Sports Sciences Association.