Today’s post is more or less an addendum or brief update to THIS article I wrote a few months ago answering the question “how much weight should I be using?

For many lifters – rookies in particular – it’s a perplexing task to figure out what’s an appropriate load to be using on any given lift or exercise. Is it too little, too much, just right? It’s a Goldilocks paradox to say the least.

Some people have an innate sense of intuition that kicks in and are able to figure things out over the course of a few weeks or months. They’re able to adopt the concept of consistent progressive overload (making the effort to do more work over time) and make continued improvements and progress towards their goal(s).

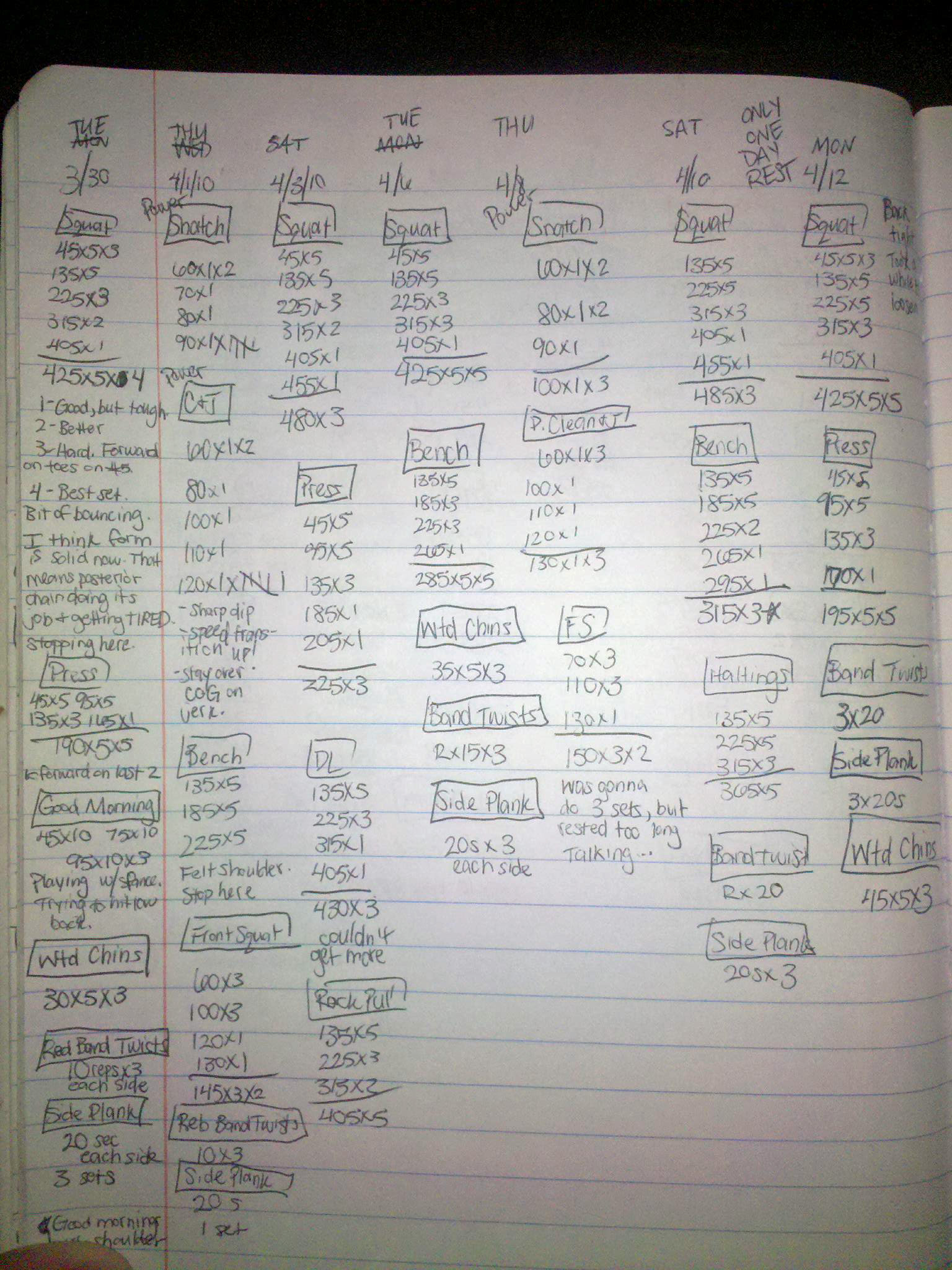

[NOTE: keeping a daily training log helps tremendously here. If you’re not doing this 1) please smack your forehead 2) do it again and 3) no, really, do it.]

Others, however, lack the Spidey-sense. I mean, I get it: walking into a weight room is daunting enough. You have some guys grunting louder than an elephant passing a kidney stone, and the fume of AXE body spray you have to walk through is enough to give you a contact high. Those two things alone are super intimidating for some people.1

What’s more, there are a bevy of other factors to consider: optimal # of sets/reps, rest periods, tempo, exercise order, and, of course, how much weight to use? And then, most important of all, is technique on point? It’s no wonder some people end up feeling like this:

To no fault of their own many fall into the trap of “winging it” and haphazardly choosing a weight to use for any particular exercise and stay there; week in and week out, month after month, and in worse case scenarios, even years, and often end up frustrated due to lackluster results.

How many times have you heard this from a friend, family member, or colleague:

“

Can you please put some pants on?I’ve been working out for [insert “x” number of weeks/months/years here] and I never seem to get results.”

My suspicion is that 9/10 times the culprit is the fact most people are UNDERestimating their ability and not challenging themselves enough.

This is where AMRAP (As Many Reps as Possible) sets can be handy. If I program an exercise for 8-10 reps, I’ll sometimes have the last set be for AMRAP. If, on the last set, they hit 10, maybe 11 reps I know they’re using a weight that’s challenging enough. If they end up hitting 23 reps I know they’re low-balling themselves and we need to up the load.

I’m fortunate in that I live in this pretty baller strength & conditioning bubble where I can control most – if not all – the variables when it comes to the clients and athletes I train.2

Especially for those I work with in-person.

I’m there to observe how they’re feeling on any given day, to watch technique and bar speed, and I can serve a judge and jury when it comes to weight selection during any given session.

Where things become suspect is when I’m not there to offer advice in person or when I’m working with a distance-based client and am unable to provide instant feedback.

How do I help them gauge whether or not they’re using enough weight? Or maybe too much? What happens then?

In recent years I’ve grown to be more of a fan of using percentage-based training with the programs I write, particularly for those whom I do not work with in a one-on-one fashion. I’m a firm believer in programming out workouts with specific weight and rep guidelines – if for nothing else to give them a sense of purpose or “goal” for the day. Hit “this” number then do “that.”

That said, lifters don’t always feel the same everyday. Some days they feel like a rockstar and end up deadlifting a bulldozer for reps. Other days the feel like they got run over by a bulldozer, and what was planned for that day just isn’t going to happen.

Copyright: bialasiewicz / 123RF Stock Photo

This is where the concept of AUTOREGULATION enters the conversation. Coaches like David Dellanave and Jen Sinkler have done a fantastic job of speaking to this phenomenon (more specifically referred to as BIOFEEDBACK) in recent years and how it behooves trainees to use ROM testing to figure out what variation of a particular lift is the best fit for that day.

Here’s an example (say it’s deadlift day…yay):

- Perform a toe touch screen, and note where you begin to feel tension.

- Set up as if you were going to do a conventional deadlift and perform a few reps.

- Re-test your toe touch. Is it better or worse?

- If the former, you know you’re good to go with conventional deadlift that day. If it’s latter, maybe perform the same sequence, albeit with a sumo stance or Jefferson stance?

- Re-test and see if there’s an improvement. If so, roll with that variation for the day.

- Travis Pollen wrote an excellent review on the concept HERE.

We can take the idea of autoregulation and use it to dictate our loads on a daily basis too. More to the point: we can start to introduce the concept of Auto-regulatory Progressive Resistance Exercise (or APRE).

To quote the great Tim Henriques:

“A beginner gets stronger just by lifting. Any program works for a beginner. An intermediate powerlifter needs strength specific programming to get stronger. An advanced lifter with many years of competitive experience, lifting very heavy weights, needs to program recovery into his work outs. The beauty of the APRE (Auto-regulatory Progressive Resistance Exercise) programs is that all categories of lifters from novices to experts can benefit with this type of program.”

It’s by no means a new concept. Many coaches have written about it in the past (and I have linked to their respective articles in this post).

In short, APRE is a great way to introduce flexible training and to better match loads you use to how you feel on a daily basis.

It’s not so much a workout as it is a guideline.

Here’s an easy breakdown taken from Myosynthesis.com:

| 3RM Protocol | 6RM Protocol | 10RM Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| 50% of 3RM – 6 reps | 50% of 6RM – 10 reps | 50% of 10RM – 12 reps |

| 75% of 3RM – 3 reps | 75% of 6RM – 6 reps | 75% of 10RM – 10 reps |

| Reps to failure with 3RM | Reps to failure with 6RM | Reps to failure with 10RM |

| Adjusted reps to failure | Adjusted reps to failure | Adjusted reps to failure |

And to adjust after the test set:

| Reps in third set (6RM protocol) | Adjustment for fourth set (kg) |

|---|---|

| 0-2 | -2.5 to -5 |

| 3-4 | 0 to -2.5 |

| 5-7 | No change |

| 8-12 | +2.5 to +5 |

| > 13 | +5 to +7.5 |

I’ll explain in a second, but the cool thing about this approach – and as Eric Helms noted in THIS review via the NSCA – is that it proved very successful in one study compared to traditional linear progression with regards to strength gains.

“The APRE group improved by an average of 21 lb more in the 1RM bench press test, 35 lb more in the 1RM squat test, and three repetitions more in the bench press to fatigue test than the LP group.”

Granted it’s only one study – and a relatively short-lived one (6 weeks) at that – but holy shit.

APRE is a four set system. The first two are build-up sets with the second two involving two sets to failure. The third set is a “test” set where you perform as many reps as possible with your 3RM, 6RM, or 10RM. From there, depending on how many repetitions you get, you adjust the weight on your fourth (and last set).

This is a brilliant system, and one that can be implemented to help people better ascertain their weight selection on any given day depending on how they feel.

Lets use an example (squat – 6 RM protocol): 315 lbs

Set #1 = 50% of 6RM x 10 reps (155 lbs)

Set #2 = 75% of 6RM x 6 reps (235 lbs)

Set #3 (Test Set) = AMAP with 6RM (315)

Here is where day-to-day shenanigans come into play. How much sleep someone got the night before, hydration levels, stress at work, stress at home, and any number of other factors can affect performance on any given day. The TEST SET serves as a form or AUTOREGULATION.

Depending on the number of reps completed in the test set will dictate the load on the LAST set. See chart above.

Set #4 = ???

Can you see the value in this approach? Especially when it comes to weight selection with main lifts such as squats, deadlifts, and bench press?

I hope so, because it’s very effective and simple to implement. And I know what some of you may be wondering: “what about the 3RM and 10RM protocols?” Well, as it happens, Tim Henriques constructed a BOMB spreadsheet that you can download for free – HERE – which allows you to pluck in numbers at your discretion for each protocol. Holla!

Now you have no excuses not to push yourself harder in the gym. Go get it.

with “how much weight did you use last week?”

with “how much weight did you use last week?”