Attempting to set a PR every single week is silly.

It’s an approach to training I have long advocated against (and a hill I will die on). Well, that and saying Sydney Bristow is the best character in television history…;o)1

Training to get stronger isn’t necessarily about hitting PR’s on the regular. In fact, if you break down the training programs that most really strong people follow, they’re only hitting an actual PR once, maybe twice per year. And that’s even a stretch.

Today’s guest post by personal trainer Lance Goyke (whom I first met back in the day when he was an intern turned employee at IFAST in Indianapolis) helps to shed light on why chasing weekly PRs likely isn’t going to do you any favors.

Why Attempting to Set PRs Every Week is F&*#!@# Stupid

“PRs never look pretty.”

Well they could look pretty good, but most people don’t have the discipline for that kind of training.

If you’re the type of person who often has two weeks of awesome training followed by two weeks of remedial rehab, then it’s likely you spend too much time testing strength instead of building strength.

In this article, we’ll talk about strength, how it’s not quite what we think it is, and how striving for strength prevents you from actually building strength. I’ll give you a few examples of how biomechanics can change during max effort lifts, hopefully leaving you with a new, healthier, and more effective way to approach your training.

What is Strength? How Do We Measure It?

Strength is “the capacity of an object or substance to withstand great force or pressure”.

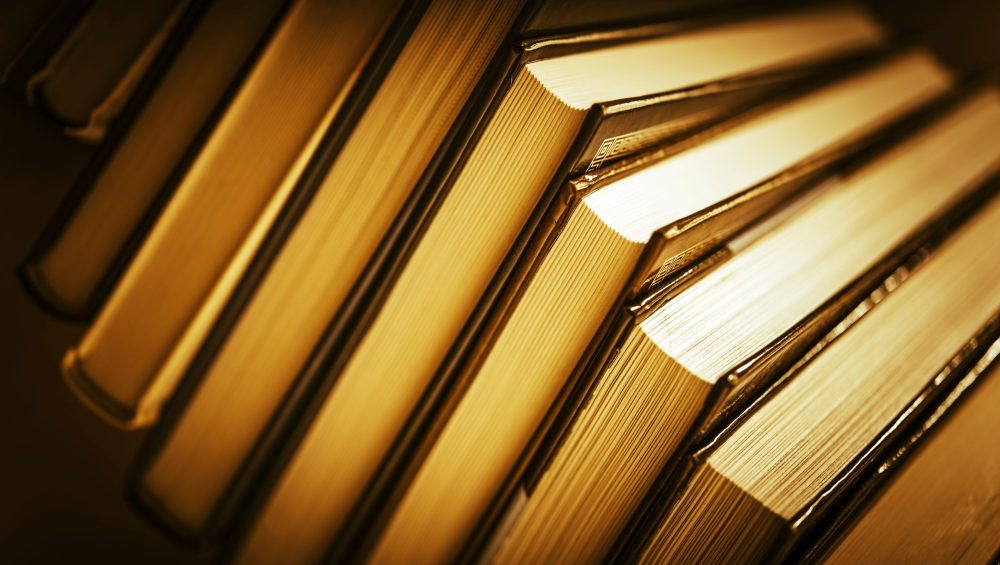

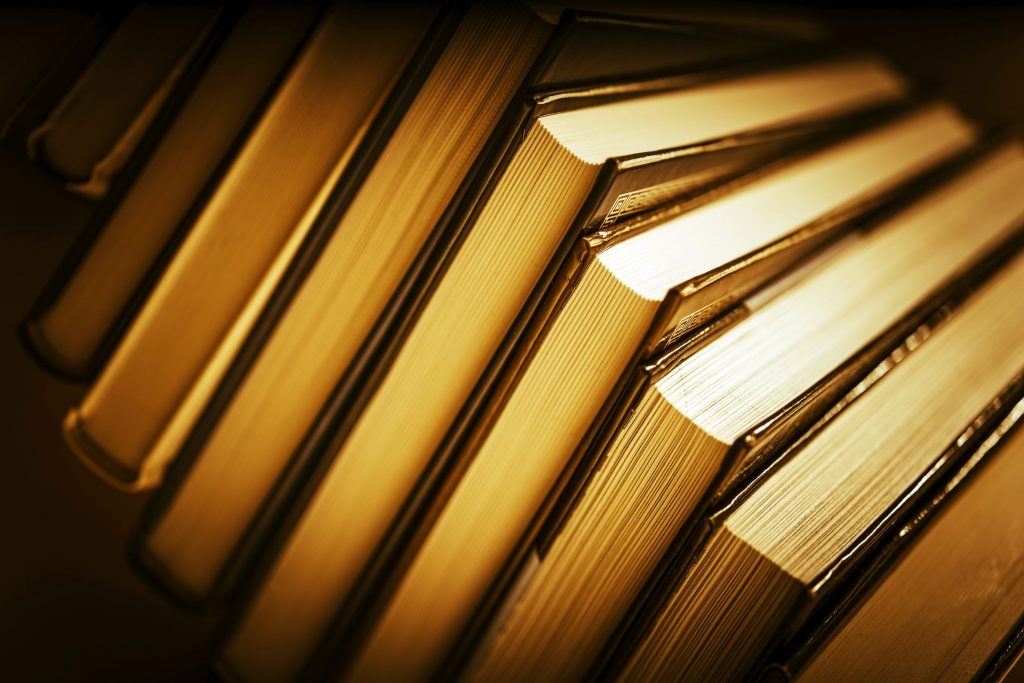

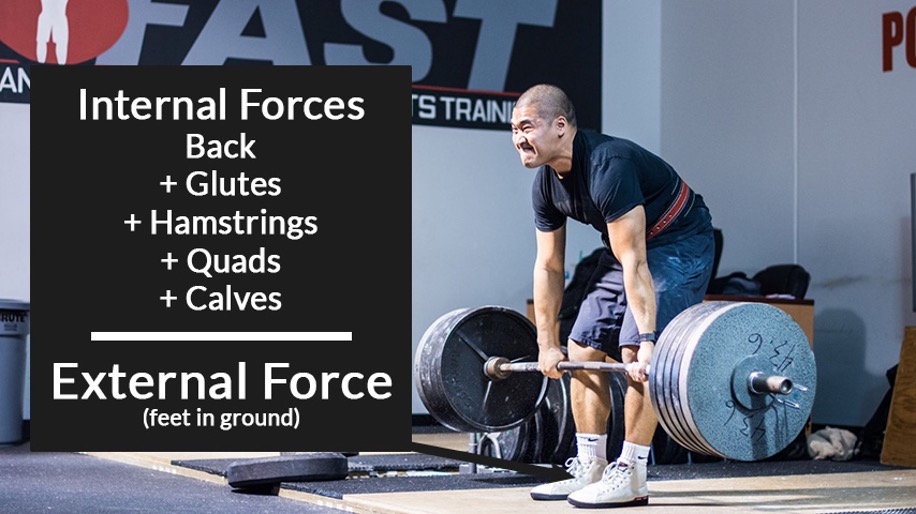

We measure it using the weight we lift in a training session, but that’s only an approximation of force production. And there are two types of forces: internal and external.

Internal forces sum to become an external force. Using deadlifting as an example, the calves, quads, hamstrings, glutes, and back muscles (internal forces) all combine into pressure through the feet (external force).

Internal forces combine into a single external force during deadlift

We mostly picture muscles and tendons producing forces, but the joints and ligaments do as well. Though bones and ligaments don’t shorten like muscles, they also don’t collapse under heavy loads.

Err, well, hopefully they don’t collapse. “Bend and not break” as they say!

I find it helpful to think of these bones and ligaments as really good isometric contracters, i.e., they maintain length even under load. It reminds me of hitching a deadlift or putting an Atlas stone in your lap. They won’t pick up the weight for you, but it sure is nice to have a short break in the middle of the rep.

Since muscle is the only thing we have that changes length and can actually move a weight, we should aim for more muscle force production.

But setting PRs isn’t about training muscles, it’s about lifting weight. And this has consequences.

Anatomy of a Personal Record

When attempting a (literal) max effort lift, there are two main factors that decide the outcome:

- Mindset

- Biomechanics

The strongest people in the gym are good at mindset: I will get this done at any cost. If you don’t think you can lift it, your brain puts the brakes on your muscles. You don’t have to be totally insane, but you do need to believe that it’s in the realm of possibility.

Biomechanics is harder to predict.

Even isolation exercises like lateral raises hardly occur in isolation. The intricate web of neurology means that moving one joint moves all the others.

During a PR attempt, your brain gives commands and listens for feedback. You might go into a bench press with the intention of keeping your shoulders set down, but when the weight slows to a near stop, your brains says, “BATTEN DOWN THE HATCHES! SHRUG THE SHOULDERS! LIFT THE BUM!” And before you know it, you’re doing an Unsupported Decline Press from Shrug Position instead of a Bench Press.

We’ve all seen someone do this, but why does it happen?

Technique Changes During PR Attempts to Temporarily Increase Force Production

If the pecs, deltoids, lats, serratus anterior, and triceps can’t stabilize AND press the weight, a useful strategy is to shrug the shoulders, jamming the shoulder into the acromion process while stabilizing the rib cage and clavicle with the neck muscles. This not only removes stress from the primary muscle groups of the lift, but also subtly changes the length of these working muscles. If the pecs are getting weaker because they’re getting shorter, let’s just elevate the clavicle to lengthen them and our force production capability will return.

But this comes at a cost. The shoulder joint wears out, rotator cuff gets injured, and the neck stiffens. All for a temporary increase in weight lifted.

And it’s difficult to argue that you’re even getting stronger! Yes, you might lift more weight, but most of that came from passive tissues instead of muscle. Even if you don’t get injured, are you planning on training your glenoid labrum to lift more weight next time? I hope not.

This type of technique change works for testing the max weight you can lift, but it’s not building strength.

Learning Technique Consistency

When a lifter tests strength by compromising biomechanics every week, she never learns how to maintain technique under duress.

Undesired Response to Increased Intensiveness

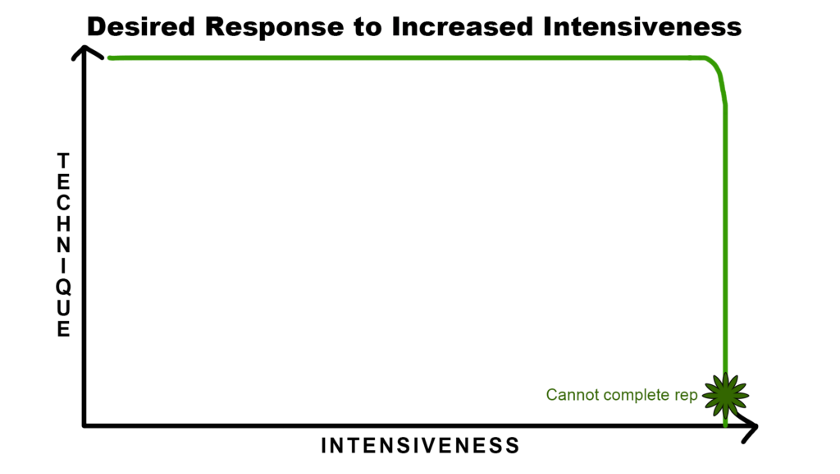

With time and extreme discipline, however, technique stays pristine even in the most difficult sets:

Desired Response to Increased Intensiveness

Many moons ago, I was having trouble staying consistent with training. I wanted to lift, but I had this two-week cycle of feeling good vs. joint pain. I stayed “broken” until I became strict about periodizing my training intensity and maintaining technique during really heavy sets.

If your training oscillates between wonderful sessions and remedial sessions, learn to be more consistent with technique across all sets and remember to deload your training monthly.

Examples of How Technique Changes During Max Effort Attempts

To cement this idea as a reality, here are three more examples of how changes in technique can prevent you from building strength. These will increase in complexity as we go along.

Deadlifting with Hitching Into Lockout

There are three main ways to lock out a deadlift:

- Squeeze glutes (good)

- Squeeze the low back (bad)

- Hitching (you do what you gotta do)

Using the glutes keeps the spine neutral. Using the low back muscles arches the lumbar spine, introducing tons of wear and tear.

Hitching a deadlift is when the lifter briefly rests the bar on the thighs while trying to lock out.

Here’s a timestamped video showing a clear hitch, though it’s difficult to nit pick when the weight is 937lbs (@ 6:12).

This has many advantages for lifting more weight:

- Short “rest”

- Squat knees underneath the weight for support

- Shorten moment arm on glutes

- Increase moment arm on quads

If you hitch to lock out your deadlift, you’re deloading the glutes and hamstrings.

Squatting with Forward Weight Shift

Shifting forward at the bottom of a full squat is a common compensation for squatting more weight. You see it a lot with Olympic weightlifting due to the mobility demands of the sport.

Here’s a timestamped video example (@ 2:58).

This does a few things to help the lifter:

- Stretches the quads and calves, stimulating a strong reflex which helps straighten the knee

- Short break time with the butt and hamstrings resting on the calves and ankles

- Removes stress from the glutes and hamstrings

- Helps maintain a vertical torso

The biggest long-term issues with this forward weight shift are that the lifter is more likely to experience knee overuse injuries, hip mobility limitations like butt wink, and inconsistent performance. The latter is an especially important topic in technique-intense Olympic weightlifting: if you only get six attempts at a meet, you don’t want to miss one because of technique.

Additionally, quad overuse often makes people feel persistent tightness. They search for quad stretches, perform some, then feel better for a few minutes until the tightness returns.

You can still get the stretch reflex benefit out of the bottom of the lift even when avoiding a forward shift. Sitting down and slightly backward to full depth stretches the quads and calves, but also increases the stretch on the glutes and hamstrings. This is one reason why posterior chain exercises like the Romanian deadlift and good mornings can improve your squat.

Bench Press with Torso Twist

Alright, I wanted to throw in one complicated scenario: twisting the torso on a bench press.

Up until now, all of our compensations have been pretty symmetrical. But there’s asymmetry in the real world. Time to take off the training wheels.

When attempting a max effort bench press, the sternum will often move to the right. This changes a few things:

- The right abs go into overdrive

- The left ribs and elbow flare out

- The left shoulder rises up due to this rib position

- The bar tilts and twists, loading the right side even more

- The lifter makes a face that’s not usually very cool (obviously most important)

Here’s a timestamped video showing the right sternum twist (@ 1:29); you can see it on rep 7, hard to not see on rep 8, and impossible to ignore on the 9th, failed rep.

Here’s a timestamped video showing the left elbow flare and bar twisting (@ 1:59).

And here’s a timestamped video showing both; the sternum start noticebly twisting on rep 15 (@ 3:29) and it’s really easy to see the left elbow flare on the failed rep.

And briefly, notice that it’s harder to nitpick mistakes in this 675lb bench press (timestamped @ 5:00).

We contort ourselves this way because of the normal asymmetry in the body. The heart on the left supports the left rib cage flaring. The big liver on the right supports the right abdominals. And because everything is connected, these asymmetries permeate all the way through our limbs.

This is a tough compensation to fix. You might consider warming up with some dedicated shoulder mobility exercises. Utilize more unilateral training like the split squat. If this problem is unfamiliar, you might find it useful to slow down as this gives you time to notice when mistakes happen (it’s usually around the sticking point). As you get more proficient, you can speed up.

In any case, you’ll need to be disciplined about your technique when you’re exhausted.

Building Strength vs. Testing Strength

Hopefully by now you have a better idea of how your body might compensate during a max effort lift. Remember: it’s okay to try hard! The point is that technique must remain pristine if it’s to be considered training.

Save the strange body conformations for your personal record attempts. And give yourself time to train between testing sessions.

I like to push my clients hard on week 4 of a 4-week training program. This gives 3 weeks to practice technique and acclimate to the training volume, preparing well for testing your body and mind.

Perfect technique does not mean the lift is light and easy. In fact, it should be harder to do because the muscles are reaching their limit and your brain must override your body’s instincts. This is real discipline.

I’ll leave you with a bulleted list of tips.

Guidelines for Building Strength

- Test strength at most one out of every four weeks

- “Testing strength” does not mean a single rep maximum, but a max effort for the pre-planned training program set and rep scheme

- Train like a bodybuilder; aim to feel the right muscles working

- Using less weight doesn’t mean you’re detraining; strength can fluctuate up to 18% in any given day

- Don’t forget to deload your training roughly one out of every four weeks

- Don’t forget to train endurance

- Use cardio to speed up your recovery from strength workouts

And remember: spend more time building strength than testing strength.

About the Author

Lance Goyke, MS, CSCS has been a personal trainer and strength coach for over ten years. He’s currently working remotely with clients all over the world, including at Google, America, Scotland, and New Zealand. In addition to coaching, he also produces educational fitness writing, videos