Today’s guest post comes courtesy of Thomas Campitelli, a Starting Strength Coach and one of Mark Rippetoe’s lead lecturers for his Starting Strength Seminars.

A Brief Backstory: A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away Back in early September, Cressey Sports Performance coach, Tony Bonvechio, wrote THIS article for my site explaining some of CSP’s general philosophies with regards to squatting (and in particular some useful drills to help people squat deeper).

A disagreement followed. An internet scuffle if you will.

(You can read the article then peruse the comments section if you’re curious.)

It seemed some people took issue with Tony’s view on torso angle during a squat. It was interpreted – falsely – that Tony was against a forward lean (which he is not). He, I, and the rest of the CSP staff just prefer that people not fall forward – and “fight” to try to maintain more of an upright torso – when coming out of the hole.

NOTE: much of the fault was my own. I had used a picture – without permission – from a Starting Strength seminar showcasing what I believed to be proper depth for a squat (Tom, the author of the article below took the pic). Given some of the messages in Tony’s article, however, and the fact that Starting Strength takes a slightly different approach (maybe 5-10% different) to the squat, some people were irate. And that’s their prerogative. Upon request I took the picture down, but it did open up the floodgates for a few commenters on what I felt, was a non-issue.

For his part, Thomas chimed in and he and I were able to keep things civil without ad hominem attacks or making fun of each other’s moms.

He offered to write a guest post to elucidate more on his side of the “debate.” I was down with the idea because 1) I’m awesome and 2) I feel it’s important as a fitness professional to stay cognizant of insights or opinions that may not necessarily jive with mine. Too, I feel it’s important to relay good information – whether I agree with it 100% or not – so that people reading can make up their own mind(s).

This is an excellent read.

The Low Bar Squat

The barbell squat is a foundational lift for the acquisition of total body strength. Although the squat can be described as “sitting down and standing up again,” its performance with a heavy weight is both physically and technically challenging.

There are three main variants of the barbell squat: the front squat, the high bar back squat, and the low bar back squat. Leaning over during the low bar squat helps to make the movement more effective. Further, for most purposes and trainees, the low bar squat should be your movement of choice.

Strength is your ability to exert force against an external resistance. It is the most general and fundamental of any human physical or athletic characteristics. Everything you do with your body requires force production at some level and without adequate strength a given physical task cannot be accomplished.

If you wish you train for strength, the movements you choose should embody the following criteria:

- Utilization of the most muscle mass possible

- Employment of that musculature over the longest effective range of motion

- Usage of the heaviest weight you can handle with good form

By combining these elements together, you can become stronger in a way that is unrivaled in its effectiveness.

The low bar squat fully meets these criteria.

Let’s begin the discussion of how to do it.

Where you place the barbell determines a number of things about how you squat, specifically how much you will lean over during the movement. Forward lean in the squat is a misunderstood concept and one that is often equated with poor outcomes–injury, inflexibility, lack of athleticism, and hurt feelings– none of which need actually occur.

Every squat variant utilizes some inclination of the torso with respect to the ground. In the low bar squat, leaning over is fundamental to the movement. It is not a form fault. Instead, it is desirable–an expression of good technique that allows you to meet the criteria above.

To squat a weighted barbell safely, you must be in balance. The center of mass of the barbell and your body’s center of mass must be directly in line with your balance point–the middle of the foot.

If you move the bar down the back so that it sits in the shelf formed between the contracted posterior deltoids and spines of the scapulae, this will affect what you do to stay in balance. To keep the bar over the middle of the foot, you will need to lean over as you descend.

How much you lean over depends upon the relative lengths of your torso, thigh, and lower leg to one another. These relationships, called anthropometry, and how much forward lean is required will vary from lifter to lifter.

If you move the bar about two inches up the back so that it sits on top of the trapezius, as is done with the high bar squat, the amount you need to lean over is less than before. Further, if you move the bar in front of the neck so that it rests on the anterior deltoids, as is done in the front squat, the torso angle is more vertical yet. You cannot lean over very far in a heavy front squat, or you will dump the bar on the ground.

These differences in torso angle affect joint angles and how the muscles must act to produce motion around those joints.

Placing the barbell lower on the back requires an active contraction of the musculature of the upper back and torso to hold it in place. Leaning over on the way down also elongates the adductors, or the groin muscles, and hamstrings in ways the other squat variants do not. Muscles only produce motion around the joints through contraction, or shortening.

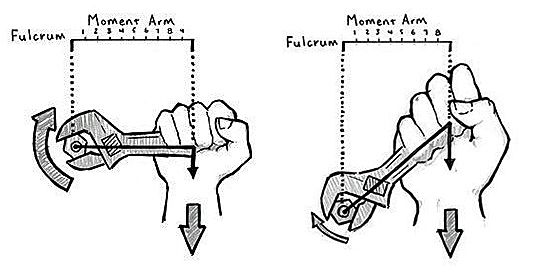

If groups of muscles are already shortened, they cannot be as effectively used to extend the hip during the ascent of the squat. Leaning over produces more leverage against hips as the torso acts like a wrench against the hip joint.

In order to maintain the normal anatomical relationships between the vertebrae and avoid flexion, the erector spinae are called into hard isometric contraction. By keeping the pelvis locked in place with respect to the spine and driving the knees out, the forward lean elongates the adductors while preventing the hamstrings from shortening during the descent of the squat. The inclination of the torso required by the low bar squat forces the lifter to utilize the most muscle mass possible.

The bottom of the low bar squat occurs when the adductors become fully elongated. For just about all people, this happens when the crease of the hip descends below the top of the knee cap by approximately one to three inches.

Full depth in a properly done low bar squat is determined not by powerlifting judges, but by anatomy.

Going deeper, such as continuing to descend until the hamstrings touch the calves, will force some of the musculature to relax when performing a low bar squat. The knees will travel further forward, shortening the adductors and hamstrings, or the spine will flex as the pelvis rotates downward.

Perhaps some of both will occur.

In either of those cases, you lose control of your back position and probably your back angle, too. Muscles shorten without moving the weight up and tightness is lost. This violates the first criterion mentioned above. Going too deep in the low bar squat requires some relaxation and therefore prevents the full utilization of the musculature.

Safety and efficiency align perfectly here.

When the muscles do not manipulate the skeletal levers effectively, poor positioning results. Spinal flexion and relaxation under a load are the frequent results. Good technique not only allows you to lift more weight through the recruitment of the most muscle mass, it also keeps you safe.

This is why the second criterion above uses the qualifier “effective” when describing the longest range of motion. You do not want to sacrifice muscular involvement in the squat for a slightly longer range of motion. You need to go below parallel.

Every time.

However, you do not need to touch your hamstrings to your calves if doing so necessitates relaxation and poor positioning.

There are volumes more to say about squatting and low bar squatting in particular. However, this is merely an introduction. Leaning over in the low bar squat is both essential and beneficial.

It allows for the most muscle mass to be used over the longest effective range of motion. This enables the lifter to handle heavier weights and to increase their physical strength both efficiently and safely. Next time you perform a low bar squat, lean over while keeping the bar in balance over the middle of the foot.

You will be doing it right.

About the Author

Thomas Campitelli is a Starting Strength Coach and photographer who lives in Oakland, CA. He is a lecturer and platform coach for Mark Rippetoe’s Starting Strength Seminars and travels throughout the North America and Europe teaching others to lift. When not on the road, he maintains a barbell training practice at CrossFit Oakland where leaning over during the squat is encouraged.