You would think, based off all the alarmist articles I come across on the internet extolling the sentiment, that everyone walking around – you, me, leprechauns1, everyone – has tight hamstrings.

And as a result, if you do a search on Google, you’ll come across roughly 8, 089, 741 (+/- 41, 903) articles telling you why, how, and when to stretch them.

Tight hamstrings have been to blame for a lot of things, including but not limited to:

- Back pain.

- Knee pain.

- Shoulder pain.

- Any sort of pain.

- Male pattern baldness.

- Global warming.

- The reason why I haven’t taken the garbage out (again, much to my wife’s dismay).

And while tight hamstring can be the root cause of some of those things, to always put the blame on them is a bit reductionist and narrow-minded to say the least.

In short: It’s the default culprit for lazy coaches and personal trainers to gravitate towards.

To steal a quote from Dr. John Rusin from THIS recent T-Nation article:

“If you’re stretching your hamstrings every day for months (or years) on end without improved flexibility, mobility, movement patterning, or pain relief, it’s not working. And it’s time to get out of this rehab purgatory.

If you aren’t seeing results from stretching, then it’s not only a waste of time, but it may be working against you. The thing is, muscles don’t get longer; they maintain a certain tone or tightness based on neurological impulse. So yes, strategic stretching DOES work in terms of reducing tone and tightness (in the short and long term), but if it hasn’t worked for you by now, it’s probably not going to.”

To steal a quote from myself:

“In order to increase the length of a muscle you need to either 1) lengthen bone (um, ouch!) or 2) in the case of someone who truly presents as short or stiff, increase the total number of sarcomeres in series (which takes a metric shit-ton of stretching).

Ask physical therapist Bill Hartman how long someone really needs to stretch in order to have a significant affect and/or to add sarcomeres, and he’ll tell you the starting point is 2-3, 10 minute holds per day. Working up to 20 minute holds.

That cute 30-second “stretch” you’re doing (most likely incorrectly) isn’t really doing anything.”

Are You “Tight” or Just Out of Whack?

You’d be surprised how often it’s the latter.

Simply put: most people aren’t so much tight as they are “stuck” in a poor position.

It goes back to something physical therapist and strength coach, Mike Reinold, brought up in casual conversation not long ago:

Which is more important to hammer first: stability or mobility?

Those trainers and coaches who swing on the stability side of the pendulum tend to be the overly cautious type who have their clients stand on BOSU balls for 45 minutes.

Those who swing on the the mobility side of things sleep with their copy of Supple Leopard every night.

Neither approach is inherently wrong so much as they’re flawed (if haphazardly assumed as “correct” for every person, in every situation).

If you strengthen (stabilize) in misalignment you develop an imbalance. If you stretch (mobilize) in misalignment you develop instability.

Take someone who presents with excessive anterior pelvic tilt. It’s not uncommon for said person to complain about constantly “tight” hamstrings, and no matter how often they stretch them, they stay tight.

You would think that after weeks, months, or sometimes even years of non-stop “stretching” they’d see some improvement, right?

Wrong.

The reason why they feel tight all the time has little to do with their hamstrings, but rather pelvic positioning.

Unless you address the position of the pelvis – in this case, excessive anterior pelvic tilt – you can stretch the hamstrings until they stop making those shitty Transformers movies (when will it end?) and you’ll never see an improvement.2

Think about it this way: in this scenario the reason why the hamstrings feel tight is because they’re lengthened and firing on all cylinders. By stretching them you’re just feeding into the problem in the first place!

We could easily chalk this up to the classic Lower Cross Syndrome as popularized by Dr. Vladomir Janda and stretch what’s tight (hip flexors, erectors), and that would be a step in the right direction.

Cool.

But I feel for most people, most of the time, that’s not going to solve the problem.

Instead, for the bulk of people, addressing things like anterior core strength (deadbugs, anyone?) in addition to active hip flexion and extension drills, like the Core Engaged Active Straight Leg Raise, is going to be money.

Real Life Example Of Not (Really) Tight Hamstrings

Take one of my clients, Dima. For all intents and purposes he’s someone who presents as “tight” AF in the hamstring department.

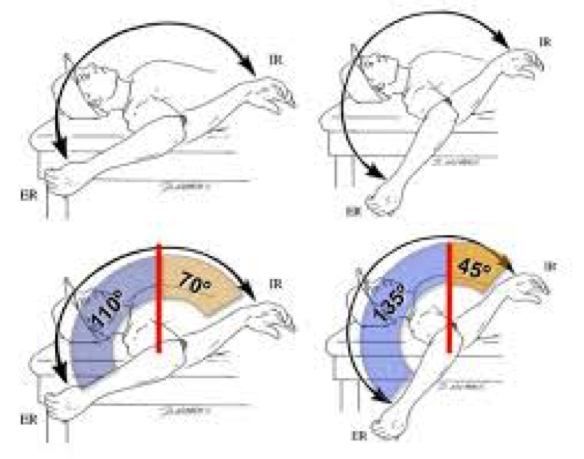

To throw him under the bus a teeny-tiny bit, if we tested his Active Straight Leg Raise this very minute anyone who’s taken the FMS would grade him the following way:

Note to Dima: You’re my boy, Blue!

The thing is, as poor as his ASLR appears, I can get more range of motion passively. Meaning, if I were to manually “stretch” his hamstrings I can nudge a bit more ROM.

Since this is the case, wouldn’t it make sense to have him stretch his hamstrings?

Meh, not really.

Now, in Dima’s case, I’m not saying we avoid stretching his hamstrings. He is someone who’s a candidate for doing so (and we do), albeit I don’t prioritize it nearly as much as some coaches/trainers may do.

Instead I have perform stuff like this:

Whaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaat

That’s some Gandalf type shit right there.

NOTE: Yes, I recognize he’s still unable to get full knee extension, but you can clearly see his ROM improved and the ease at which he got the additional ROM is night and day compared to the start.

All without stretching.

My boy Dean Somerset does a better job than myself explaining the mechanism at play here:

“Part of it is matching the active ability to achieve the position with the passive range of motion that’s available. If they can passively get there, they’re not “tight” or “restricted,” they just may not have the strength or motor control in that specific position, so doing some hip flexion movements can help build context of how to get there so that on their follow up test, they have a better knowledge base of active hip flexion capability to get into.”

In the end, don’t always assume everyone needs to stretch. A little active range of motion in conjunction with TENSION can go a long ways at building context and improving ROM.

.jpg/290px-Annie_Mac_(2).jpg)

wrong. I don’t condone being one of those trainers who is all about doing an exercise only because it looks cool and fun. The better you know your anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, and pain science, the more potential you’ll have to be a great coach.

wrong. I don’t condone being one of those trainers who is all about doing an exercise only because it looks cool and fun. The better you know your anatomy, physiology, biomechanics, and pain science, the more potential you’ll have to be a great coach.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches. I’m not going to hit on every point above today. I’d encourage you to check out Mike Reinold’s site and/or look into his and Eric Cressey’s

I’m not going to hit on every point above today. I’d encourage you to check out Mike Reinold’s site and/or look into his and Eric Cressey’s