In the realm of fitness and strength & conditioning we’ve all heard the phrase:

“You need to stimulate the muscle to grow, not annihilate it.”

I can’t say I disagree with the sentiment, albeit I do feel it’s a bit reductionist taken at face value. I mean, assuming someone isn’t injured or has a history of injury, most people can train a whole lot harder than they give themselves credit for.

I’ve said it in the past and it bears repeating here:

“Lifting weights isn’t supposed to tickle.”

Furthermore, if you pick the brains of coaches like Alex Viada or Chad Wesley Smith they’d be the first to champion the notion that you should annihilate muscle. Or, to be more fair: do more work. Or to be even more fair: follow a carefully structured, periodized, undulated, (possibly) concurrent plan that fluctuates training stress.

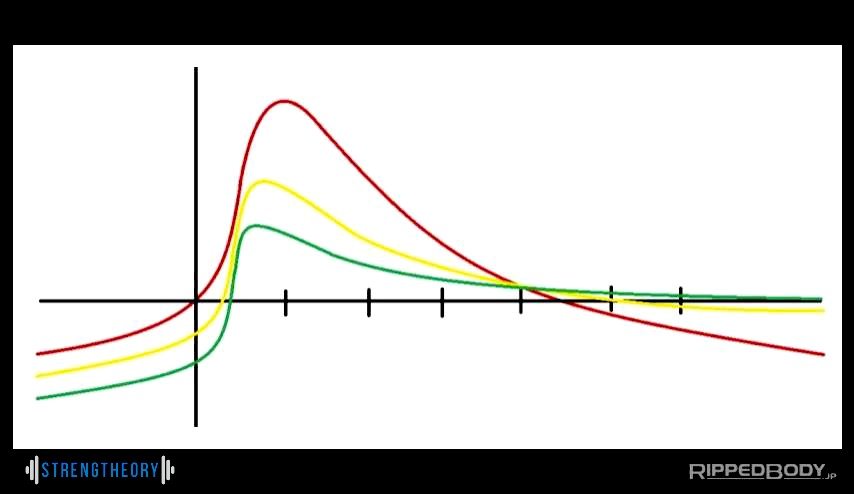

Photo snaked from Greg Nuckols courtesy of Andy Morgan’s site RippedBody.jp.

Those are big words to some people. In non-geek speak all it means is: do more work, but not all the time…smartly.

To quote Pat Davidson:

“I’m a strength coach which means I am a stress manager more than anything else. The only difference between me and your shrink is that I want to dump as much stress on you as I possibly can to see what you can survive. If it doesn’t kill you, it will likely make you stronger.”

That’s about as succinct of a way to describe things as can be put. Any strength coach worth his or her weight in barbells knows most programs written (geared towards strength and performance) should consist of alternating patterns of high stress (whether it be accumulation, intensity or both) with low stress.

You can’t just take the word “annihilate” and implement that mantra 100% of the time and expect to make continued progress. We’re not Terminators. Fatigue will always masks one’s true fitness.

Not into graphs? Me either. They make my head hurt.

Think of it this way: lets say you test your 1RM in the deadlift. 315! Not too shabby you sexy beast. Now, go run a 5K. Don’t ask questions, just do it.

When you finish we’ll immediately re-test your 1RM deadlift.

Do you think you’ll sniff close to 315 lbs again?

Not a chance.

Overtraining?

Fatigue doesn’t mean overtraining. The internet loves to toss out the word overtraining, as if it’s an easy thing to attain. Trust me: you’re not overtrained. Just because you squatted two days in a row or, I don’t know, took a CrossFit class, doesn’t mean you’re overtrained.

You have to go really, really (REALLY!) out of your way to come remotely close to overtraining. To put things into perspective: The Iron Cowboy, James Lawrence, completed 50 triathlons in 50 days (in 50 States) and he wasn’t overtrained. I’m sure he felt like shit, but he wasn’t overtrained.[footnote]If YOU tried this, you would be overtrained. A lot of planning and meticulous attention to detail went into this accomplishment. Plus, there’s a degree of “being a psycho” that comes into play too. I woud DRIVE 50 miles in 50 States, let alone do what he did. Amazing.[/footnote]

Which is why I respect guys like Alex and Chad who prefer to provoke/nudge people to work harder (but smartly) and not be too analytical about everything. That’s the only way to assure adaptation and continued progress (and PRs).

What Does “Smartly” Even Mean, Tony?

Good question.

It can mean a lot of things, but here are some quick, random, bullet-point ideas/points to consider:

1. You’re Not an Elite Athlete (Sorry, I’m not Sorry)

Using James Lawrence as an example or THIS article about how to max out squats everyday, lets take an objective look at things.

I have no issues with squatting everyday, or people who decide to actually do it. In fact, I thought the article was brilliant and had a lot of great and innovative things to say. But, as I remember it a few years ago, within 24-48 hours of the article going live on T-Nation, I received a swarm of emails from random dudes asking me if they thought it would be a good idea if “they too?” should train everyday?

I had to try really hard to resist the urge to throw an ax into my face.

NEWSFLASH: you’re not an elite athlete!!!!!!!

Unless you have 4-6 hours per day to train, and that’s literally all you do, it’s probably not going to be a good fit.

Lets be real: For many people (not all), you read an awesome article, and right then and there, decided it’s “exactly what you needed.”

In theory, it sounds amazing. But here’s the thing – you make the Tin Man look hypermobile. The last time you lifted anything remotely explosively was back when Patrick Swayze was rocking stone washed jeans. And, the last time I checked, you sit in front of a computer for 8-9 hours per day, and actually work for a living.

You have the time for this when?

Listen, I get it, you like to exercise. What’s more, who am I to say that people shouldn’t be enthusiastic to train more often and actually move around a bit more? I encourage that, wholeheartedly!

But come on people – lets not put the cart before the horse.

Actually, scratch that. I’m not opposed to people training (hard) everyday. I mean, there’s definitely a way to do it right and I think that’s what many people should strive for. They just shouldn’t train balls to wall (ovaries to wall?) every single day.

What I don’t agree with, and think is borderline dangerous is when people read an article about ELITE athletes whose sole job is to train – and who have been doing this type of training FOR YEARS – and then run out to their local globo gym, try to be a hero, and hurt themselves the third day in.

Trust me – it will happen.

I swear, I’m going to do a social experiment someday, write an article detailing how running over your right arm with a car repeatedly will somehow increase testosterone levels by 317%, and see how many people email me asking for more info.

NOTE: I like what Bret Contreras had to say on the topic. HERE’s a old(er) blog post he wrote on how to incorporate daily training into the mix.

2. Deadlift Less

Yep, you read that correctly. I just told my reading audience to deadlift less.

What’s next? Me telling everyone to perform more kipping pull-ups? Eat tofu? Admitting I had it all wrong and that Tracy Anderson was right all along: women should avoid lifting anything above 3 lbs. LOLz.

Relax. Deep breaths. Give me a second to explain.

Once you reach a certain level of strength (lets say 2x bodyweight) there’s a point of diminishing returns with regards to deadlifting more than once a week. I’d argue the deadlift is the most “draining” – both physiologically and neurologically – on the body compared to squatting, bench pressing, etc.

Maybe it’s more anecdotal on my end, but I’ve found – through a lot of trial and error – that whenever I deadlift (heavy) more than once per week my body hates me.

Too, I find this to be pretty accurate for most other people.

I’ll often limit “max effort” work (85% + of 1RM) to once every 2-3 weeks for most people. Rarely will I ever have someone hit that level every week.

I will, however, include more speed/technical work into the mix and typically have no qualms implementing this more than once per week. It may look something like this:

Day 1 – Deadlift Cluster

Week 1: 4×4 (70%), one-rep every 15s.

Week 2: 3×4 (75%), one rep every 15s.

Week 3: 5×2 (80%), one rep every 15s.

Week 4: 3×3 (65%), one rep every 15s

Day 2 – Speed/Technique Work

Week 1: 8×1 (60%), rest 30-45s.

Week 2: 10×1 (60%), rest 30-45s.

Week 3: 12×1 (60%), rest 45-60s.

Week 4: 6×1 (70%), rest 30-45s.

3. Include Less Mechanical Loading

I feel many trainees miss the boat in using their own bodyweight as load. Fellow Cressey Sports Performance coach, Greg Robins, is a big fan of including less “mechanical loading” into some programs (including my own) to help stave off “annihilation” and still gain a lot of benefit.

I hit the big lifts pretty hard, and I don’t necessarily need to make myself hate life any further with my accessory work.

Try this:

Bodyweight Bulgarian Split Squats For Time

Week 1: 3 sets of 30s/leg (FML)

Week 2: 3 sets of 40s/leg (Seriously, FML).

Week 3: 4 sets of 40s/leg (Hahahaha).

Week 4: 3 sets of 60s/leg (Kelly Clarkson! Watch the clip below for the reference.)

If you really want to up the ante do the above, but a controlled tempo up and down (2s down, 2s up; 3s down, 3s up).

4. Go For Walk

Totally not kidding.

Casual walks work wonders in terms of recovery. And you don’t need to make this some sort of heavy backpack walking or sled dragging uphill for AMRAP hybrid. Tone it down, killer.

Just walk. Enjoy it.

5. Deload (Volume)

At CSP, we generally “save” week 4 of each program for a deload week. For starters it fits our training model well because each athlete/client gets a new program every month anyways (billing cycle is every four weeks).

While I don’t go out of my way to introduce too many new exercises with beginners – they don’t need a ton of variety – those who have been working with us for a while will usually get a slew of “new stuff” and their ass handed to them in week #1. The deload week prior serves as a way to better “prepare” them for the onslaught inevitably coming.

Generally speaking, on a deload week we deload overall volume, and keep intensity (as a percentage of one’s 1RM) at high level.

NOTE: not to jump into the weeds too far, but going back to the topic of overtraining, if someone does enter that territory, they tend to do so as a result of too much volume and not so much with intensity.

As such we’ll either decrease volume with the MAIN LIFT of the day, but keep intensity up:

Squat

Week 1: 5×5

Week 2: 4×5

Week 3: (5) 3×3, 2×6

Week 4: 3×3

Or we may decrease overall volume (tonnage) via reduced accessory work.

And yes, sometimes, we’ll tweak both volume AND intensity. It just depends (typically this is reserved for those in a competitive season. Think: powerlifter).

There are numerous ways to “deload” – OMIT all axial loading for a week, maybe perform a bodypart only split, maybe reduce training days from 4-6x per week, to 3x per week, nothing above 70%, play kickball, I don’t care, you know your clients better than I do – but as whole, I find reducing volume (yet keeping intensity up) bodes well for most people.

Your Turn

The above is in no way an exhaustive list. I could keep going, but I doubt many have made it this far anyways. If you have, 10 points to Gryffindor!

Do you have any thoughts on the topic? Any ways you like to “not annihilate” your body? Share them below.