Today’s guest post comes courtesy of Gavin McHale, a Certified Exercise Physiologist from Winnipeg, Canada (in his words, straight north of Fargo). Gavin attended a workshop I did with Dean Somerset in Minneapolis a few weeks ago and he wanted to write up some of the things he picked up from it.

Read on to find a breakdown of how you can clean up your shoulders and hips, lift more weight and allow yourself to relax, just by changing the way you breathe.

4 Ways to Fire Up Your Belly

Let me paint you a picture.

A client or physical therapist refers someone to me and they walk in ready to get their ass handed to them. After our initial conversation, I tell them we’re going to start the session with some breathing drills.

They often glaze over and assume it means something else, until I tell them to lie down and take a deep breath.

“Wait, you just want me to breathe?”

“That is correct.”

Almost every time, I can provide a new client a take-home benefit with a couple of breathing cues, all inside the first 2 minutes on the gym floor.

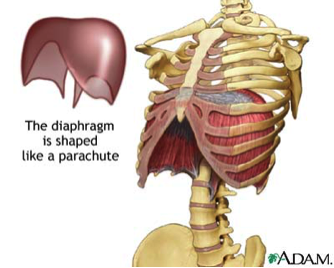

Image courtesy of Crossfit Southbay, via A.D.A.M

Why, you ask? Well there are lots of reasons why breathing is a good practice to get into, and I’m not talking about the breathing we do mindlessly, day-in day-out. I’m talking about mindful “diaphragmatic” or “belly” breathing.

We live in what I’d call a very sympathetic world. Our sympathetic nervous system, also known as fight-or-flight, is cranked up all the time. We have to drive to work in traffic, get a project done, feed the kids, manage the mortgage… you get the point.

All this stress kind of shuts down our parasympathetic nervous system, also known as rest-and-digest. You know, the one that fixes all our shit? Ya, that one.

The diaphragm is actually intended to be our body’s primary breathing muscle, but as a consequence of modern life, it’s been shunned like Tony and I are by all those cat haters (I see you). Instead, the much less efficient breathing muscles of the upper chest and neck then must take over, creating all sorts of issues.

Although it doesn’t look very sexy, diaphragamatic breathing allows us to create a better balance between fight-or-flight and rest-and-digest, and could be the key to fixing a lot of movement issues as well.

When we breathe, this dome-shaped muscle contracts, allowing the lungs to take in air. What we should see is the stomach rising as the dome compresses the abdominal cavity. This is why I tell my clients to try and “get fat” if they’re having trouble figuring it out. I often see the exact opposite, and while it may present a more pleasing side profile, it only allows the lungs to partially expand and results in weaker core stabilization.

So why do we do it?

Not only is it a good idea to get back to the muscles we should be using for an activity like breathing, but an under-active or dysfunctional diaphragm is going to lead to movement issues as well. Neck and shoulder issues are the bulk of what I see, but back and hip irritation have also been linked to breathing concerns.

Proximal stability leads to distal mobility.

If we can create more stability in the core and centre of the body, the limbs and other areas where we need to be more mobile are free to do their job as well.

Test/Re-Test

Below, I’m going to give you several tests to try based on areas that you may have trouble with or issues you want to clean up. The protocol here is to test the movement, correct with a breathing drill, the re-test to see if it got better.

If it did, great! If not, we may have to do some more digging. The breathing correctives are outlined at the end of the article.

1. Shoulder Issues

I found it very interesting how many people had shoulder pain and dysfunction when I first started training. I cleaned up their technique, had them pull way more than they pushed and focused on opening up their thoracic spine. Things got better, but never really got better, ya know?

Then I went further down the rabbit hole and recognized there was more to it. I realized that almost all shoulder problems are somehow tied to breathing mechanics, and a couple of simple drills can make a world of difference, especially when done consistently. Here are two (related) tests to see where problems may lie and outline the path to correcting them.

Shoulder Test/Re-Test #1: Active and Passive Shoulder Flexion

*Ideally, the shirt is off for all tests of shoulder function. Although it can be awkward, this allows someone to see exactly what the scapulae are doing during these movements.

You may have to stand against a wall to do this properly, but stand tall and proud and slowly brings your hands up over your head in front of you. Your ribcage should stay down (the back should stay against the wall) and the head should stay in a packed position (no poke-necks).

How high did your arms get? Was there any pain?

Here is Tony showing an example of a bad active shoulder flexion (left) and a good active shoulder flexion (right). If you’re not careful, you may think the “bad” test is better than the good one. A closer looks reveals that Tony is flaring his ribcage, overextending his lower back and poking his head forward. The test on the right is a true test of his active shoulder flexion. Not bad T, but why is your shirt still on?

The passive test is the same as the active test, only lying down on your back. The knees should be bent and feet flat on the floor or table. The ribcage should stay down and lower back flush to ensure a true test.

We will review correctives later in the article.

Shoulder Test/Re-Test #2: Scapulo-Humeral Rhythm (probably need a friend for this one)

Stand in the same position as your active shoulder flexion test, but this time we’re going to bring the arms overhead by your sides, trying to touch the backs of your hands together above your head.

As the arms move overhead, the scapula should rotate ½ as much as the humerus does. So, to get overhead (180 degrees total), the humerus should rotate upward 120 degrees and the scapula should rotate the remaining 60 degrees.

Image courtesy of BEST Performance Group

If there is any pain with this movement, you should see a registered healthcare professional (or refer to one, if you’re a trainer).

However, if you’re a trainer and you notice the scapula isn’t moving as it should (i.e. the medial border isn’t at 60 degrees) see if you just help it along by manually moving it to the desired position.

Better? Great, let’s get to breathing and fix that shit. Still painful? Refer.

2. Back Issues

Everyone who’s ever had or worked with people with back issues raise their hand! Ya, a lot of us have, myself included and it’s no fun. Whether it’s chronic back pain or a little tweak here and there, worrying about blowing your back out is a real concern for many people.

They’re scared to lift things around the house, scared to bend over the wrong way and especially scared to lift a shit-ton of weight off the floor in the gym (covered later). We can’t be having that… let’s fix it.

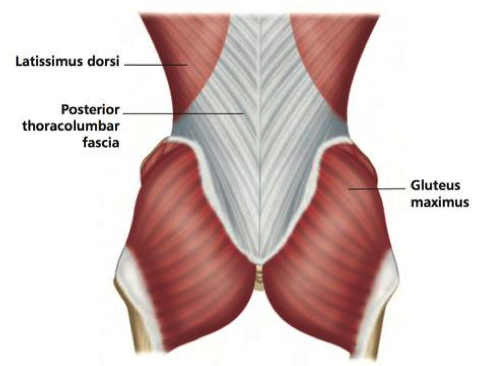

I said that lower back and shoulder issues can be related because their main structures are intimately connected via the thoracolumbar fascia. You can see the lats (major players in the shoulder) and the glutes (major players in the lower back) in the image below. If you have issues getting your arms overhead, you may very well have lower back problems as well, and vice versa.

Image courtesy of Neil Asher Healthcare

Back Test/Re-Test #1: Active Straight Leg Raise

This one is nice and simple. Lie on your back, legs straight. Lift one leg as high as you can before you stop or you feel pain. The knee should stay straight. Note how high you got. A good score is 90 degrees with no movement in the opposite leg.

Image courtesy of www.FunctionalMovement.com

Back Test-Re-Test #2: Passive Hip Rotation (bring that friend back, you’ll need em)

Lie flat on your back with legs straight and lift one leg. Bend the leg at the knee, coming up to 90 degrees hip flexion. Move the hip into external rotation (foot to opposite hip) and internal rotation (foot outside hip) while supporting the knee. Note the angle achieved with each movement. A good score is 90 degrees from midline for external rotation and 45 degrees for internal.

Photo courtesy of geekymedics.com.

LIFTING HEAVY A.F.

(if you have to ask what it means, you’re not ready for it)

There’s no question that if you’ve ever done a heavy squat or deadlift and not wrecked your back, you know that you need to be able to create massive amounts of tension through your core. If you can’t, you get hurt, pretty simple.

The diaphragm plays a massive role in stabilizing the core. It forms the lid on the “core box”, working with the obliques, QL, pelvic floor and transverse abdominus. Being able to take in air and maintain a high-pressure area in the abdominal cavity is crucial for lifting heavy (another reason I start with breathing drills).

RELAXATION

Remember that sympathetic world I spoke about earlier where most of us live that wreaks havoc on our breathing patterns? Needless to say, it can also create difficulty with relaxation and sleep.

I’m pretty sure most of us (and our clients) can agree we’d like to sleep better.

So, when you watch the videos below, don’t just put them in the “workout” box, but remember they can also have a positive impact on your ability to relax and even fall asleep.

Not only will these breathing drills assist in improving movement patterns, they’ll set up the context for creating tension before and during a heavy lift.

THE BREATHING CORRECTIVES

Prone Crocodile Breathing

If you’re new to the diaphragmatic breathing game, this is your place to start. Maybe you scored poorly on one of the above tests or you have an itch to throw more weight on the bar but aren’t yet comfortable doing so.

Either way, give this drill a shot before moving on.

Prone Lengthening

This one is particularly useful if you have trouble with your shoulder and/or struggled with the shoulder flexion and scapulo-humeral tests. Many people’s shoulder dysfunction comes from a number of factors, one of those being tight/ropey serratus anterior. This drill will help to release that muscle, allowing it to do it’s part in moving the scapula to get that arm overhead.

The serratus anterior (SA) works in concert with the upper traps (UT) and lower traps (LT) to allow the scapula to upwardly rotate.

Note From TG: props to Dr. Evan Osar for introducing me to this exercise a few years ago.

Crook Lying Belly Breathing

This is another great beginner drill as the lower back is supported and the table or floor can provide external feedback. This is also the best position for belly breathing, allowing the belly to fully expand. Along with the others, this one is great for those with back or hip issues.

Quadruped Breathing

This is another great drill for those with issues rotating that scap when going overhead. The serratus anterior is a massive player and if we can get it rotating properly (or at least better than it was), we may be able to provide relief and learn what it is we need to focus on moving forward.

So there you have it, a good, hard look at what we should be looking for and how to make it better, just by changing the way we breathe.

One final note for trainers, make sure you try these yourself as you may find that different cues work better. If you do, please tell me. I want to know all your secrets!

OBLIGATORY PROMOTIONAL PLUG FROM TG (sorry not sorry)

Pretty much everything discussed above is covered in more detail in mine and Dean Somerset’s Complete Shoulder & Hip Blueprint which is being released this week (Nov. 1st).

In fact the site goes LIVE tonight. You can check back HERE at midnight to get in on the action. It’s totally going to be like a Harry Potter book release! Except, you know, without wizards and Sorting Hats and shit.

Author’s Bio

Gavin McHale is a Certified Exercise Physiologist from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (straight North of Fargo).

Gavin McHale is a Certified Exercise Physiologist from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (straight North of Fargo).

He loves getting people to lift things they never imagined they would both in-person and online.

He also likes to lift said heavy things and, much like Tony, loves cats.

Check him out at www.gavinmchale.com.