Being or not being healthy, by and large, is rarely an information problem. Most people know regular physical activity is good for their health, as is not crushing an entire bag of Doritos right before bed.

Why, then, are so many of us struggling with attaining a “healthy” lifestyle?

Simple (but not really): Lack of behavioral interventions.

In today’s guest post strength coach and PhD to be, Justin Kompf, discusses the dilemma.

Why Is It So Hard To Be Healthy?

Four facts keep me thinking on a consistent basis.

- The majority of us are overweight or obese

- The majority of people who lose weight will gain it back

- The majority of us are getting insufficient amounts of exercise; and

- The majority of people who start an exercise program will quit within six months

Physical inactivity contributes to 9% of premature deaths.

Maintaining a healthy body weight and exercising regularly are two of four health behaviors (the other two being not drinking your face off and not smoking) that can extend a person’s life by over a decade.[footnote]Note From TG: that and spoonful of Unicorn tears, daily.[/footnote]

Mathematically, the odds of a person doing two behaviors is lower than doing one behavior, and the percent should keep getting smaller as more behaviors are added on.

Still, the number is staggeringly low.

Only 4.8% of us do all of these health behaviors. Stated otherwise, 95.2% of people either have a poor diet, are insufficiently active, drink too much, smoke, or do some combination of the four behaviors.

Why Don’t People Do These Health Behaviors?

I was recently at an interview for a new training job and my interviewee asked me why I train people.

It’s because we sell time. We can give people additional high qualities years on their life so that they can continue doing what they love to do.

The question of why; as in, “why don’t people do these healthy behaviors” sits around in my mind a lot. The question of adherence also hangs out up there.

The environment exerts such a strong influence on us that it makes it challenging to be healthy. I would also say that most people lack an appropriate plan and a strong enough form of behavioral regulation.

Environmental Influence

We live in an ‘obesogenic environment’.

The term “obesogenic environment” refers to an environment that promotes gaining weight and one that is not conducive to weight loss. This environment helps, or contributes to, obesity.

So, quite literally when we try to lose weight or exercise there is a fight against the environment.

Imagine going to work, trying to get a project done but Jim the cubicle invader keeps barging into your office to talk about his weekly Tinder dates. Then, because he thinks it’s funny, he flips your desk too.

That’s what weight loss is like in our environment, keeping focus despite distractions and going back to work despite setbacks.

What to do Then?

Full disclosure, I don’t have all the answers. Everyone is different so a one size fits all answer would be a disservice. All I have is experience and a decent understanding of behavioral research.

So, what to do?

In my opinion, the best thing a person can do no matter what is to simply start.

That being said, as people start, there are things I would encourage them to do in regards to their behavioral regulation.

Whenever someone sets a goal, they have a motive.

For example, “I want to lose 20 pounds” or “I want to gain 10 pounds of muscle” are both motives. They are a person’s WHAT and are a part of a person’s goals.

WHAT’s also have WHY’s.

A person’s WHY is their form of behavioral regulation.

People can be extrinsically motivated or they can be intrinsically motived.

Intrinsic motivation refers to doing an activity out of sheer enjoyment. But, let’s face it most people won’t always run, lift or eat broccoli for sheer enjoyment.

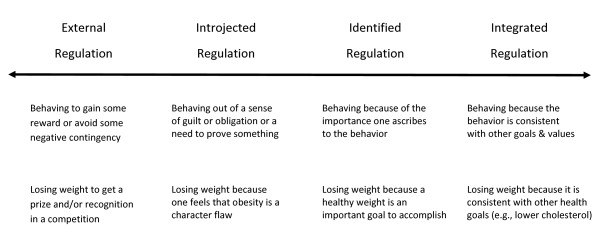

Within extrinsic motivation are four different categories. They are (see chart above and below) external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, and integrated regulation.

| Regulation type | Description | Example |

| External regulation | Achieve an external reward or avoid punishment

Compliance with demands from others |

Exercising because of doctor’s orders |

| Introjected regulation | Avoiding shame, enhancing ego or pride | Exercising to avoid feeling guilty |

| Identified regulation | Acceptance of the value of the behavior | Exercising because it is important to do so |

| Integrated regulation | Behavior is congruent with a person’s values and needs | Exercising because the outcome is valuable

Being fit is part of one’s identity |

Behavior Change is Like Battle

Recall, the obesogenic environment is programmed to make us fat. In order to overcome it there must be a ‘fight’ against it.

Most behavioral theories discuss a motivational phase and a planning phase.

Motivational phases are the precursor for a planning phase. A person has to have some form of motivation (i.e. not be amotivated) to make a plan.

However, it certainly helps in the planning phase to have a strong form of behavioral regulation (why you are motivated to do a behavior).

Here’s how I think about it; when a person goes to battle they have their own strengths as well as a weapon of choice.

Thor doesn’t go into battle without his hammer (RIP Mjolnir), Luke Skywalker doesn’t leave his light saber at home, and the Punisher (watch this series[footnote]Note From TG: DO IT. It’s LEGIT.[/footnote]) is always packing.

These heroes also have their plan.

The Punisher doesn’t just go in guns blazing, he’s tactical. Luke Skywalker blows up the death star with a good plan (Thanks Rogue One) but gets his hand cut off when he takes on a challenge that is too big for him.

Think of motivational regulation as a person’s strength and think of the plan of attack as the strategy for success.

The more powerful your weapon (or the weaker the adversary), the less necessary a specific plan becomes.

If a person loves weight lifting (intrinsic motivation), they wouldn’t really need instructions to make a specific plan because nothing can stop them. Odds are they would make plans with no help.

In geek language, Superman wouldn’t need a plan to beat a common criminal. His strength is sufficient to just get the job done.

Strength and Plans

Any form of motivational regulation is enough to get a person started. However, there are some forms that are more likely to keep a person going.

If motivational regulation is closer to the extrinsic side, the challenge shouldn’t be made too hard. Barriers are likely to derail people like this.

To me, having external regulation to fight the obesogenic environment would be like Luke Skywalker going to fight Darth Vader with a rubber chicken.

He’s going to need a damn good plan to win, and even then, it’s likely that he will get his other hand chopped off.

| Regulation type | Description | Metaphor |

| External regulation | Achieve an external reward or avoid punishment

Compliance with demands from others |

Rubber chicken |

| Introjected regulation | Avoiding shame, enhancing ego or pride | sling shot |

| Identified regulation | Acceptance of the value of the behavior | One of those laser guns Chewbacca has |

| Integrated regulation | Behavior is congruent with a person’s values and needs | The force and a lightsaber |

On the other hand, if a person wants to achieve a goal because the behavior is congruent with their life values (i.e. to be a better parent) that’s the same as going into a fight with the full use of the force and a lightsaber.

You still need a plan, but you’re better equipped to win.

Planning Phases

Planning phases dictate specifically when, where and how a behavior is going to occur.

For example, if someone decides that eating more vegetables will be beneficial to their health, they should plan exactly when and where they are going to eat vegetables.

These plans are called implementation intentions. They link situational cues to desired behaviors.

If a person wants to eat more vegetables they might say “when it is my lunch break I will have the bag full of baby carrots I brought to work”

I propose that a stronger motivational foundation when paired with specific planning will contribute to more favorable outcomes.

| Motivational foundation | Planning phase | Predicted behavioral outcome |

| External regulation

|

Weak | |

| Introjected regulation | Implementation intention formation | Moderate |

| Identified regulation

|

Strong | |

| Integrated regulation | Very strong |

What to Do?

With a weak foundation (i.e. external or introjected) plans are more necessary but still likely not as effective as if they were based on a strong foundation (i.e. identified or integrated).

There are many reasons why people fail but I consider behavioral regulation to be an especially important one.

Changing motivational foundations is challenging. A weight loss goal is great. However, as people go through the process they should try to find activities that they love doing. For example, they could do the following:

- Try a variety of exercises and see which one makes you feel great, ones you love

- Set a small goal: (1) do 1 pull up (2) do one perfect push-up (3) run a 5k (4) learn how to master a squat or a deadlift

- Learn to make new foods that taste good and are also healthy

- Try connecting your goal to a different value. Sure, losing weight will make you look better but it will also make you healthier which means you will have better quality time to do the things you love doing. Try making the link between your goal and life values.

Reference

Ford, E.S., Zhao, G.Z., Tsai, J., Chaoyang, L. (2011). Low-risk lifestyle behaviors and all-cause mortality: Findings from the national health and nutrition examination survey III mortality study. American Journal of Public Health 101(1): 1922-1929.

Author’s Bio

Justin is a PhD student in the exercise and health sciences department at the University of Massachusetts at Boston. He is a certified personal trainer and certified strength and conditioning specialist. Justin blogs at Justinmkompf.com.

You can follow Justin on Facebook HERE.