Getting hurt is a drag.

It’s even more of a drag when you’re someone who’s used to being active and an injury prevents you from training consistently or prevents you from training as hard as you’d like.

There’s generally two approaches many people take:

1. Complete rest.

2. Conjure up their inner Jason Bourne and grit their teeth through it.

Neither is ideal in my opinion.

I take the stand that injury (or training with a degree of pain <— sometimes) is inevitable. As I’ve jokingly (but not really) stated in the past…

…”Lifting weights isn’t supposed to tickle.”

Pain, pain science, and how to train around pain is a very complex and nuanced topic. This is a blog post, not a dissertation.

To that end, today I want to take some time to discuss a few strategies on how to train around pain that don’t revolve around the extremes: Sitting on the couch watching Netflix or plotting to take down Treadstone.

Full Disclosure: Much of what I’ll cover below is in Dr. Michael Mash’s online resource, Barbell Rehab, which is currently my new spirit animal of favorite continuing education courses.

Factors to Consider When Training Around Pain

Let’s begin with the definition of “pain.”

Pain

/pān/

noun

1. A localized or generalized unpleasant bodily sensation or complex of sensations that causes mild to severe physical discomfort and emotional distress and typically results from bodily disorder (such as injury or disease).1

2. That feeling you get when your significant other wants to talk about feelings or what your eyes see when you watch someone perform 117 kipping pull-ups.2

More precisely we often associate pain with actual damage. However, pain doesn’t always have to gravitate around that denominator.

Pain can also be equated to a smoke alarm alerting the body that something is awry:

- Hey, bicep tendon here: I think I’m close to snapping, can you tone it down on the bench dips?

- Hey, knee cap here: I’m about to end up on the other side of the room if you don’t fix your squat.

- Look out – a ninja!

More to the point, pain is multi-faceted and can manifest a plethora of ways, which is why it’s imperative to educate people that it isn’t always centered around a physical injury.

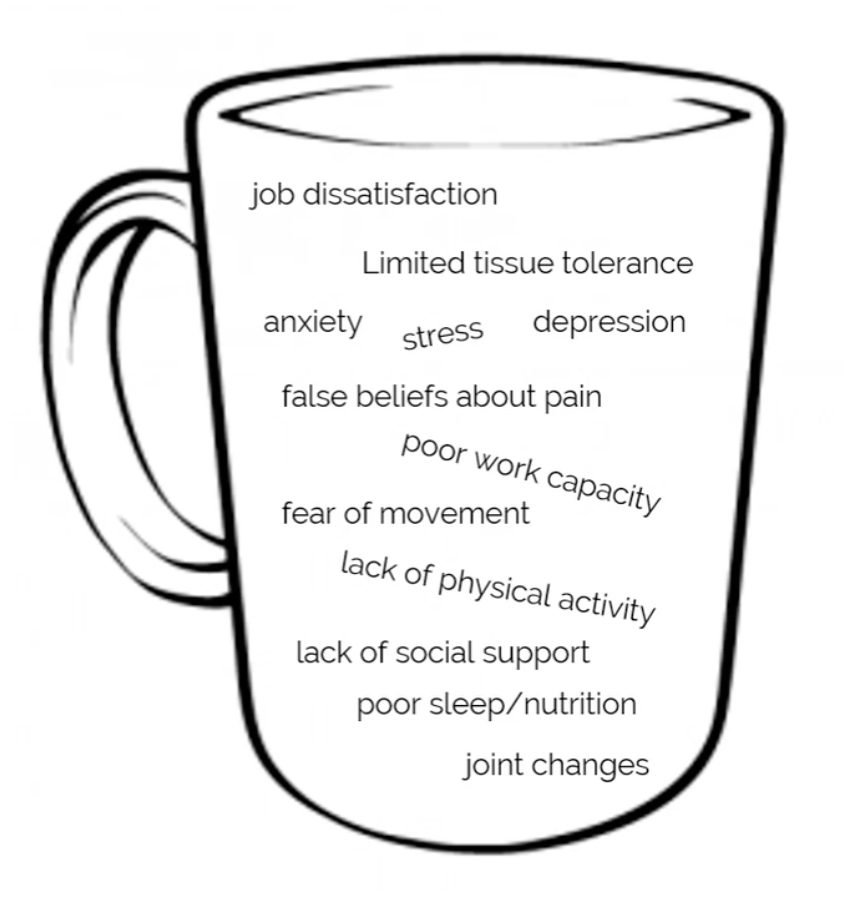

Take for instance this cup analogy highlighted in a 2016 study from the medical journal Physiotherapy: Theory & Practice titled “The clinical application of teaching people about pain” by Louw, et al.

Pain is like a cup, and there are many factors that can fill it up.

Moreover, you can address people’s pain in one of two ways:

1. Reduce the contents of the cup.

2. Make the cup bigger (via appropriately progressed strength training)

As Michael addresses in Barbell Rehab, there are several ways to build a framework to train around pain that don’t involve being passive, subjecting yourself to corrective exercise purgatory, or in a worse case scenario…surgery.

1. Technique Audit

When someone comes to CORE for an assessment with me and they go into great detail on how bench pressing bothers their shoulder(s), rather than spending 30 minutes assessing how much shoulder range of motion they have, waxing poetic on the myriad of drills they can perform to improve thoracic extension, and/or going into the weeds on diaphragmatic positional breathing mechanics I’ll instead do this really out-of-the-box thing where I’ll ask them to…

…wait for it.

…wait for it.

…here it comes.

…show me their bench press.

More times than not, all that’s needed is a subtle technique fix on their set-up and execution of the lift itself and their shoulder hates them less almost instantly.

This isn’t to say we’d ignore other factors like thoracic mobility and breathing mechanics altogether; especially of deficits exists. However, I’ve found that most people are less inclined to want to light their face on fire from corrective exercise boredom if I just cut to the crux of the issue at hand.

Their shitty technique.

2. Programming Audit

This is a point I remember Dr. Quinn Henoch of Juggernaut Training hammering home when I listened to him present a few years ago.

How often do you audit your programs?

Has it ever occurred to you that maybe, just maybe, the reason why you (or your clients) are hurt is because you were a bit overzealous with an exercise variation – or, more commonly, you were too aggressive with loading – and that that was the culprit of your’s (or their) low back pain…?

…and not because your left ankle lacked two degrees of dorsiflexion, or, I don’t know it was windy yesterday?

Load management (or lack of it) is the lowest hanging fruit we often overlook.

Here’s an example of what I mean.

Using the same person above who’s shoulder bothers them when he/she benches: Let’s say they like to bench press 1x per week, on a Monday of course.

Like clockwork, the day after they bench, their shoulder feels like Johnny Lawrence used it for target practice with his fists.

It feels like that for a few days, dissipates, and then by the time the following bench day arrives it feels better and the same cycle continues.

A more cogent approach may be to spread out the same volume over TWO workouts rather than one.

Here’s what they normally do:

Monday: Bench Press: 6×5 @ 185 lb

(Total Tonnage = 5,550 lb)

Here’s what they should do:

Monday/Thursday: Bench Press: 3×5 @ 185

(Total Tonnage = 2,775 lb) x 2

NO MERCY!

3. Change Modifiable Factors

Pigging back on the above, when something hurts or is painful always, always, always look at volume/load first.

From there you can ascertain at what load does something hurt – what’s the symptom threshold? Find that and when you do, train just below it to build tolerance and resiliency. The result will be twofold:

1. You’ll be encouraging an actual training effect.

2. Eventually, you’ll surpass the original symptom threshold because you forced an adaptation.

An easy example here would be squats. If someone experiences knee pain at a certain depth – maybe at parallel or just below it – have him or her perform a box (or free) squat ABOVE that spot.

Likewise, maybe all that’s needed to make the squat less painful is to change the stance width, or degree of toeing out?

You can also tinker with bar position or even the tempo. The point is: Assuming we’ve ruled out anything nefarious, I’d rather someone keep squatting with a variation/tweak that reduces their symptoms dramatically than omit them altogether,

4. An Exorcism

But only as a last resort.