As a fitness professional part of the job description is the ability to answer questions. Specifically those questions posed by your athletes and clients.

This makes sense given, outside of their primary care practitioner, you’re the person your clients are trusting with their health and well-being.

Granted, you’re not curing cancer or writing prescriptions for irritable bowel syndrome or anything1. But it stands to reason that as a personal trainer or strength coach you’re numero Uno when it comes to being most people’s resource for health & fitness information.

You’re it.

You’re the go to.

And like or not…You’re “the guy (or girl)” whenever someone says “I gotta a guy (or girl)” whenever they’re asked a fitness or health related question.

Stuff like:

“Does putting a stick of butter in my coffee make it healthier?”

“Will intermittent fasting help me lose 20 lbs of fat while also increasing my squat by 55 lbs AND give me x-ray vision?”

“Is it normal not to be able to feel the left side of my face after performing last night’s WOD? Also, it stings when I pee.”

I don’t know about you, but it’s a “challenge” I don’t take lightly.

I want to be a reliable and valuable source of information for my clients. They have (a lot of) questions, and I want to be able to answer them to the best of my ability.

I don’t know everything.2 I’m not a pompous a-hole who’s afraid to say “I don’t know.”

It’s rare when I get stumped with a question, but when I do I’m fortunate to have a long-list of people I can reach out to to get the answer(s).

I know when to stay in my lane and refer out when needed. You want to train for a figure competition? Not my strong suit. You need some manual therapy? Definitely not my strong suit. That irritable bowel problem mentioned above? Don’t worry, I gotta guy.

Most questions I receive are generally un-original in nature and something I can handle on the spot.

One question I get on an almost weekly basis, while inert and mundane (but altogether apropos), is this:

“How much weight should I be using?”

It’s a very relevant question to ask. And one that, unfortunately, takes a little time to answer.

To be honest whenever I’m asked this question two things inevitably happen:

1) The theme music from Jaws reverberates in my head.3

2) The smart aleck in me wants nothing more than to respond with “all of it.”

That would be the dick move, though.

Like I said: it’s a very relevant question and one that many, many people have a hard time figuring out on their own.

As it happens I was asked this question last week by a client of mine during his training session. It wasn’t asked with regards to that particular session per se. Rather, he was curious about how much weight he should be using on the days he wasn’t working with me in person.

NOTE: the bulk of my clients train with me “x” days per week at the studio and also “x” number of days per week on their own at their regular gym. I write full programming that they follow whether they’re working with me in person or not. Because I’m awesome.

When working with people in person I have this handy protocol I like to call “coaching” where I’m able to give them instant feedback on a set-by-set basis.

I’ll tell them to increase/decrease/or maintain weight on any given exercise as I see fit.

Sometimes I even give them a sense of autonomy and allow them to choose how much weight to use.

The idea is to give them a maximal training effect using the minimum effective dose without causing harm or pain.

Challenge people, encourage progressive overload, but not to the point where they feel like they’re going to shit a kidney.

Pretty self-explanatory stuff.

Where things get tricky is when people are on their own and don’t have someone telling them what to do.

What then?

Here Are Some Options/Suggestions/Insights/WhatHaveYou

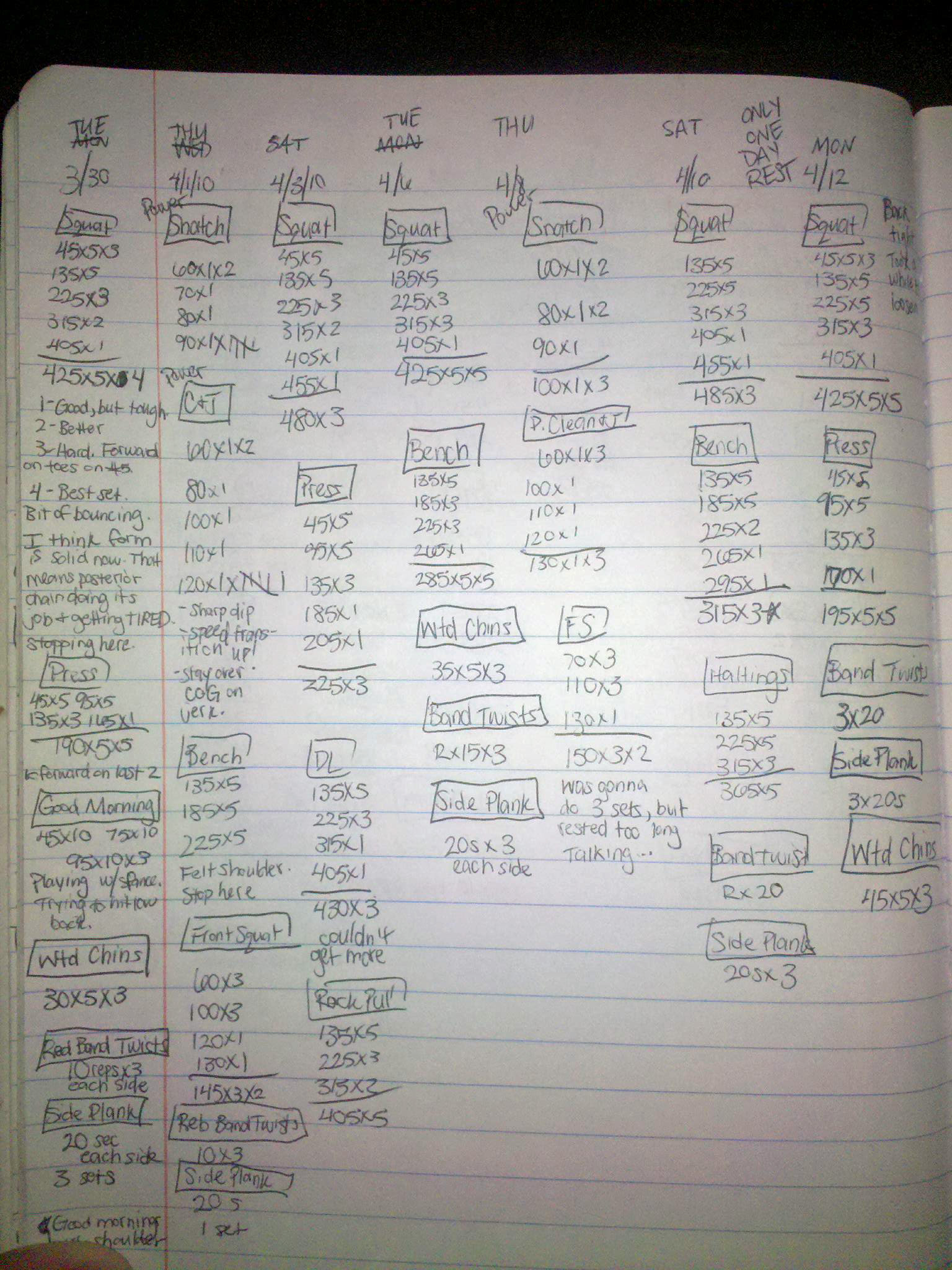

1) Write That Shit Down

In the case of my client above, when he asked “how much weight should I be using?” I responded  with “how much weight did you use last week?”

with “how much weight did you use last week?”

[Crickets chirping]

He hadn’t been keeping track of anything.

He’d simply been putting a check-mark when he completed a set, and then moved on.

I, of course, was like “nooooooooooooo.”

I can’t blame him. It was on ME for not being clearer on the importance of writing things down and being more meticulous with tracking everything.

But the fix was/is easy: write down what you did, and try to do “more work” the following week.

I realize we like to overcomplicate things, but that’s part of the problem.

Write shit down. Really, it’s that simple.

2) What Is “Do More Work?”

What does that even mean? Do more work?

It means that in order for the body to adapt, you need to give it a stimulus and then nudge it, over time, to do more work. There are numerous ways to do this in the weight room, but for the sake of simplicity we can think of “more work” as more sets/reps or load.

Do the math. If you’re keeping track of things take your total sets and reps (and the weight you lifted) and figure out your total tonnage.

Try to increase that number week by week.

One strategy I like is something I call the 2-Rep Window.

If I prescribe 10 repetitions for a given exercise, what I really mean is 8-10 repetitions.

If someone picks a weight and they can easily perform more than 10 on every set, they’re going too light. If they can’t perform at least 8, they’re going too heavy.

The idea is to fall within the 2-Rep Window with each set and to STAY WITH THE SAME WEIGHT until the highest number within the range is hit for ALL sets.

**I’d rather someone cut a set short a rep or two rather than perform technically flawed reps or worse, miss reps.

If I have someone performing a bench press for 3 sets of 10 repetitions it may look something like this:

Week 1:

Set 1: 10 reps

Set 2: 8 reps

Set 3: 8 reps

Week 2:

Set 1: 10 reps

Set 2: 10 reps

Set 3: 9 reps

Once they’re able to hit ALL reps on ALL sets, they’re then given the green light to increase the weight and the process starts all over again.

Another simple approach is one I stole from strength coach Paul Carter.

Simply prescribe an exercise and say the objective is to perform 3×10 or 15 (30-45 total reps) with “x” amount of weight. The idea is to overshoot their ability-level and force them to go heavier, but within reason.

They stay with the same weight until they’re able to hit the upper rep scheme within the prescribed number of sets.

It’s boring, but it works.

Another layer to consider is something brought up by Cincinnati-based coach, PJ Striet:

“I’ve went over and above in my program notes to explain this subject. I used to just give 2 rep brackets, and, like you pointed out here, told clients to increase weight when they could achieve the high end of the range on all sets, and then drop back down to the lower end of the bracket and build back up again.

The problem though, as I soon figured out, was that people were doing say, 4 sets of 8 (bracket being 6-8) with a weight they could have probably gotten 15 reps with on their 4th set. This isn’t doing anything/isn’t enough of a stimulus. This isn’t meaningful progression. Feasibly, one could run a 12+ week cycle in the scenario above before the 4 sets of 8 actually became challenging. And this was on me because I should have realized most people will take the path of least resistance (literally).

Now, in my notes, I tell clients to do as many AMRAP on the final set of to gauge how much to progress. If the bracket is 4×6-8, and they get 8-8-8-9, weight selection is pretty good and a 2-5% increase and dropping back down to 6 reps is going to be a good play and productive. If they get 8-8-8-20, there is a problem and I should either stab myself in the eye for being a crap coach or schedule a lobotomy for the client.”

Brilliant.

3) Challenging Is Subjective

I feel much of the confusion, though, is people understanding what’s a challenging weight and what should count as a set.

Many people “waste” sets where they’re counting their warm-up/build-ups sets as actual sets, and thus stagnating their progress.

A few ideas on this matter:

- I like to say something to the effect of “If your last rep on your last set feels the same as your first rep on your first set, you’re going too light.”

- Using a Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale is useful here. Give them some criteria using a scale of 1-10. A “1” being “super easy” and “10” being “who do you think I am, Wolverine?” Ask them to be in the 7-8 RPE range for ALL sets.

And That’s It

There’s a ton of trial-and-error involved here, but it’s your job as the fitness professional and coach to educate your clients on the matter.

It’s important to consider context and everyone’s starting point, of course…comfort level, ability, past/current injury history, goals, etc.

However, beginners are typically going to have a much harder time differentiating “how much weight to use” compared to advanced lifters. There’s definitely a degree of responsibility on the trainer and coach to take the reigns on this matter.

But the sooner they realize it’s not rocket science, that there are some simple strategies that can be implemented to make things less cumbersome (and maybe even more importantly, that there’s a degree of personal accountability involved), the sooner things will start to click.