I often joke that “lifting weights isn’t supposed to tickle.”

When you’re pushing, pulling, carrying, thrusting, and otherwise hoisting things around for the heck of it…you’re bound to end up with a few bumps and bruises along the way.1

Honestly, I can’t think of the last time my body was 100% devoid of any type of soreness or semi-nefarious “huh, well that doesn’t feel fantastic” sort of vibe.

I’m not referring to pain. Nothing that diminishes my ability to live my day-to-day life. Just, you know, sometimes my first step out of bed or sitting down to drop it like it’s hot isn’t the most enjoyable experience in the world.2

(Anyone who’s performed heavy squats the day prior can commiserate).

A lifetime of playing sports and training will do that to a body.

But that’s the point.

Lifting weights and pushing the body outside it’s comfort zone is what allows us to adapt and come back stronger and more resilient; to take on the world (or the squat rack) and tell it to GFY.

All that said: it still sucks donkey balls when the inevitable happens. We take things too far, go too heavy, or move juuuuust the right way for something wrong to happen.

Arguably, nothing stagnates or deflates progress more in the gym than a jacked up lower back.

Statistics will say that we’ve all been there. Or, alternatively, as fitness professionals, have worked with someone who’s been there.

So I figured today I’d shoot from the hip and fire back some quick-hitting suggestions/insights/alternatives to consider when working with someone dealing with low-back pain.

In No Particular Order

1) Except for this one. This is super important.

I’ll kick things off with the grandiose, off-kilter statement that if something hurts…don’t do it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a1Y73sPHKxw

Fucking profound, right?

Dr. Stuart McGill will advocate for provocative tests/screens to be performed – slump test, toe touch, McKenzie drills, etc – in order to figure out the root cause or possible source of someone’s back pain.

The stark contrast should be done outside of that window. It’s imperative as a coach, trainer, clinician, wizard, to demonstrate pain-free movement to the client/athlete. The objective should be to mute or pump the brakes on pain and start to mold more of a “movement quality” campaign.

Dr. McGill often refers to this as “spinal hygiene.”

2) Speaking of Dr. McGill

You should read his book Ultimate Back Fitness Performance. Specifically pages 1-325.

Spoiler Alert: it’s 325 pages long.

A more “user-friendly” text would be his latest book, Back Mechanic.

3) Back to “spinal hygiene.”

The good Doc refers to this as:

“The daily upkeep of your back. It includes your recovery exercise routine as well as changes to your existing daily motions all day long. Success in removing back pain requires removal of the movement flaws that cause tissue stress.”

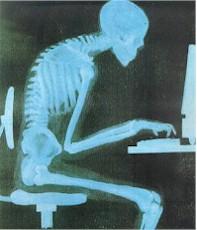

This could refer to something as simple and innocuous as teaching someone how to sit in a chair  properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.

properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.

As counterintuitive as it seems, those who have more flexion-based back pain will feel more comfortable in flexion. Likewise, those with extension-based back pain will feel at home in extension.

It’s weird.

So, often, taking the time to clean up activities and endeavors outside of the gym will be of most benefit.

As the saying goes: “we as trainers/coaches have 1-2 hours to “fix” things, and the client/athlete has 23 hours to mess it up.”

Other things to consider:

- Walking. This is an excellent fit for those with low-back pain. It’s just important to make sure they’re not defaulting in forward head posture and a slouched posture. McGill refers to this as the “mall strolling” pattern. One should be more upright and swing the arms from the shoulders (and not the elbows). This provokes more of a “pertubation” to the body helping to build spinal stability.

- Grooving more remedial hip-hinge patterns like I discussed in THIS article. Getting someone to dissociate hip movement from lumbar movement is a game-changer..

- Pigging back on the above, the hip hinge creeps its way into EVERYDAY things like brushing one’s teeth or bending over to pick something up off the ground (golfer’s lift). Anything that can be done to spare the spine (discs) and make it less sensitive to pain is a win – no matter how trivial the activity.

4) Synchronous Movement

Learning to “lock” the ribcage to the pelvis is another key element to managing back pain. The abdominal brace is of relevance here. Basically the entire core musculature – not just any one muscle (ahem, transverse abdominus (drawing in method) – needs to work in concert and fire synchronously to spare the spine and offer more spinal stability.

One drill in particular that hammers the point home is the Wall Plank Rotation.

Here an abdominal brace is adopted and the objective is to “rotate” the entire body as one unit, locking the ribcage to the pelvis. Many will inevitably rotate through their lumbar spine and then the upper torso will follow suite.

5) Neutral Spine – Always (But Not Really)

The spine IS meant to move.

Neutral spine is paramount, but it benefits trainees to tinker with end-ranges of motions (in both flexion and extension) if for nothing else to “teach” the body to know how to get out of those compromising positions – especially when under load.

During our workshops together, Dean Somerset will often demonstrate to the trainees how squatting into deeper hip flexion (unloaded, and to the point where butt wink happens) can be of benefit to some people. The notion of learning where a precarious position is (and how to get out of it) is valuable.

I’ll use the simple Cat-Camel drill to teach people that it’s okay to allow the spine move.

Also of Note: I’d argue we’ve been so programmed into thinking that all spinal flexion is bad and that a baby seal dies every time we do it, that it’s caused a phenomenon referred to as reverse posturing.

The idea that more and more people are now “stuck” in extension, and thus at the mercy of a whole spectrum of other back issues (spondy, etc).

You can read more about that HERE.

Suffice it to say: we can’t discount Rule #1…helping to build improved spinal endurance/stability.

Plain ol’ vanilla planks come into the picture here.

This:

Not This:

This:

- Keeping people honest and accountable on proper position (not “hanging” on passive restraints and dipping into excessive lumbar extension) is kinda of important.

- Rule of thumb is to be able to hold a prone plank 120s, side plank (per side) for 90s. McGill will note it’s a RED FLAG if there’s a huge discrepancy between right/left sides.

- I prefer more of an RKC style once someone is ready. This helps to build more bodily tension, to the point where everything – quads, abs, glutes, eye lids, everything – are firing. Ten seconds is torture when done right.

However, we can always graduate to less vomit in my mouthish exercises. As much as planks are baller and part of the equation to helping solve someone’s back pain, they’re about as exciting as watching a NASCAR race.

6) A few favs include:

Elbow Touches

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AUgz2U65KPc

Progressing lower and lower towards the ground.

Farmer Carries – all of them

Offset Loaded Exercises

I love offset loaded exercises for a variety of reasons. But most germane to this conversation is the fact that there’s a heavy rotary stability component when performing them.

Getting people moving and performing more traditional strength & conditioning drills – assuming they’re pain free and of high movement quality – will help to get them out of “patient mode,” and more excited to stick to the plan.

7) A Few Other Ideas to Consider

Don’t be an a-hole and marry yourself to the idea that everyone HAS to deadlift from the floor and that everyone HAS to pull conventionally.

The only thing people HAVE to do is sign up for my newsletter. (wink, wink, nudge, nudge)

Sometimes we have to set our egos aside and do what’s best for the client/athlete and what’s the best fit for them. I think the trap bar deadlift is a wonderful tool for people with a history of low back pain.

To steal a quote from Dr. John Rusin:

“Without sending you back to Physics 101, the forward position of the barbell causes a less than optimal moment arm to stabilize the core position in neutral while moving some serious loads off the floor.

During the traditional deadlift, the center of mass (barbell) falls in front of your body, therefore causing the axis of rotation of the movement to be farther away from the load itself. This all translates into increased shearing forces at the joints of the lumbar spine, putting all the structures, including intervertebral discs and ligaments at increased risk of injury with faulty mechanics of movement.”

The trap bar deadlift results in a better torso position for most people and less shear load in the spine. For anyone with a history of low back pain this is a no-brainer.

Use an incline bench rather than a flat bench when programming pressing movements. It’s just an easier scenario for most people and less “wonky” of a position to get in and out of.

Too, program more standing exercise variations – standing 1-arm cable rows, pull-throughs, landmine presses, Sparta kicks to the chest.