It’s not lost on me that the title of this post will raise some eyebrows. The title shouldn’t be taken too literally, because I do feel there are ideal approaches, methodologies, and “rules” to consider when coaching any lift in the weight room.

That said, when it comes to exercise technique (or human movement in general) why are textbooks the metric at which we compare everything?

Textbooks provide context, information, and sometimes make for handy coffee table improvers.

However, we don’t live in textbooks. What a squat, sprint, overhead press (or hell, even a carrot cake) looks like in a textbook can (and usually is) a stark contrast from what is emulated in real life.

Textbook Technique & Why It Doesn’t Exist

I do believe there are some universal tenets to coaching a deadlift or squat or bench press or kettlebell swing1 that will not only allow a client or athlete to marinate in its benefits, but to do so in a fashion that won’t increase their likelihood of injury (or their contributions to their physical therapist’s mortgage payments).

I’m interested in making people savages, but I’m also interested in the long-game. It wouldn’t bode well for business (or my reputation) if all of my client’s deadlifts looked like this:

To that end, with regards to universal tenets for deadlifting:

- Loaded spinal flexion is a no-no.

- That’s pretty much it.

If you’re following that one golden rule, you’re doing a better job than most. It’s sad, but true.

However, golden rule(s) aside, there are many intricate, more nuanced things to consider person to person. One’s training experience comes to mind. We can’t hold someone holding a barbell in their hands for the first time to the same standard as someone who’s been a competitive powerlifter for 17 years.

Likewise, someone with a vast and delicate history of lower back issues is not going to take the same path as someone with a “clean” health history. And, of course, other factors come into play such as goal(s), movement quality, favorite color, and anatomical/structural differences between individuals.

Someone with hips like this…

…is going to move differently – and presumably be coached differently – than someone with hips like this:

There are many, many fantastic resources out there that help to break down anatomy, assessment, biomechanics, joint positions, and what’s considered ideal exercise technique. I have my biases as to what I feel is correct – as does everyone – but it’s important to take every resource with a grain of salt, because…

“Textbook technique only exists in a textbook.”

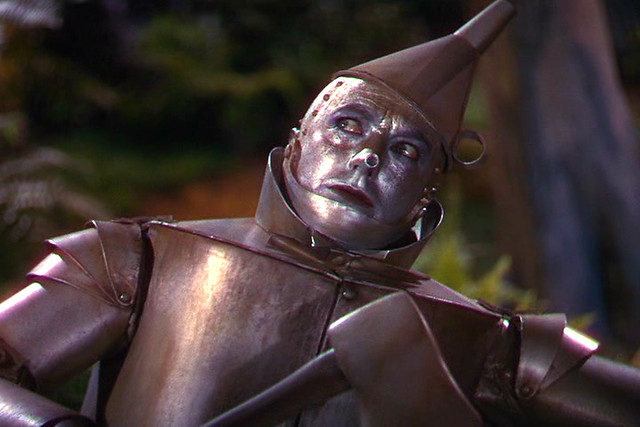

When I heard Mike Reinold say this sentence years ago my immediate reaction was this:

My second reaction was to start doing handstands down the sidewalk outside my apartment, but I didn’t.

You know, cause that’s fucking weird.

And because I can’t do a handstand.

Either way, what Mike said was/is 100% correct.

Textbook technique, in the real world, is every bit as much of a myth as detox diets making you pee rainbows or me riding a Dire wolf to work today

What we read or deem as “ideal” on paper, while often a great starting point for many people, doesn’t always translate to real-life. As coaches it’s important to understand this. Anytime we corner ourselves into one-train of thought or that any one thing applies to everybody, we’re doing the industry – and our clients/athletes – a disservice.

A Real-Life Example

A few months ago I started working with a woman who had been battling some low-back issues, yet wanted to hire me to take over her programming and help clean up her technique.

Specifically she wanted to hone in on her deadlift.

She was frustrated because no matter what she did (or who she worked with), her back always bothered her.

I like to be a fly on the wall and just watch people do their thing during an initial consult. I want to see what their default movement schemes are. In this case I set up a barbell on the floor, loaded it up with a weight I knew she could handle safely, and then asked her to do her thing. Her “default” stance was a conventional stance, and while it wasn’t the worst one I had ever seen, I could clearly see why her back may have been bothering her.

We had established earlier in her assessment that she lacked t-spine extension and her hip mobility wasn’t great either.

More to the point, after doing a simple hip scour and Rockback test, I surmised she was able to attain more hip flexion ROM with more hip abduction. An important point, as you’ll soon see.

Note: the Rockback test is a great assessment to use to figure out one’s “usable” ROM in hip flexion. The idea is to see if or when the lumbar spine loses positioning.

Bad Rockback Test

Notice when spine loses position.

Dead Sexy Rockback Test

Notice the spine stays relatively “neutral” throughout. Also, notice those triceps.

We can then compare what we see here with what we see on the gym floor.2

Going back to my client, she read a lot of articles and books on deadlifting, most of which told her that deadlifting = conventional stance. Always. Moreover, other coaches/colleagues she had consulted with in the past told her to use the conventional stance.

No exceptions.

This is what I mean by falling into the “textbook technique” trap. On paper everything sounds (and looks) great. Everyone can and should be able to conventional deadlift.

In real-life, though…not so much.

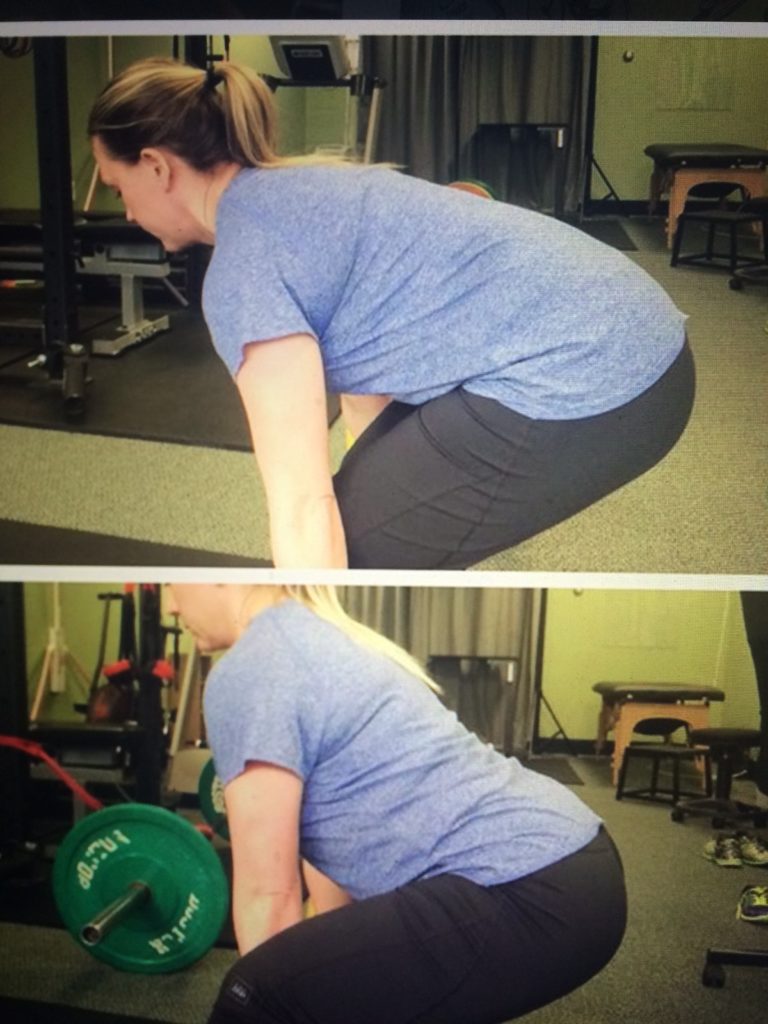

Here’s a before and after picture I took of my client. The top picture shows her original set-up with a conventional stance. The bottom demonstrates me putting her into a modified sumo stance.

Immediate improvement in her lower & upper spine position. Having her adopt a wider stance better complimented her anatomy, which then resulted in an infinitely better starting position to pull (no lumbar flexion, improved t-spine extension).

What’s more, with that modification alone she noted there was zero pain.

She left that session feeling motivated and hopeful about training. A win-win if you ask me.

I posted the above picture on some social media accounts – explaining much of what I mentioned above. And wouldn’t you know it: I was called out by a handful of coaches.

One stated the problem wasn’t with her anatomy, but that the real issue was my poor coaching. A funny assertion given he wasn’t in the room with me. Another coach agreed stating something to the effect of:

“No client has walked into “x gym” and not have been able to perform a conventional deadlift after a little coaching on day #1.”

I guess all I could have done at the time was to just go fuck myself.

I demonstrated I was able to clean up someone’s deadlift and do so in a way that was pain-free, and yet, here I was being told by a crew of All-Star coaches I had failed because I didn’t have her conventional deadlift. My actions, apparently, were on par with drop kicking a baby seal in the mouth.

Pump the Brakes

I hope people can appreciate the narrow-mindedness of this type of thinking. To expect everyone to fit into the same scheme or way of doing things because that’s what YOU prefer to do (or because a textbook told you to do so) is about as narrow-minded as it comes.

No one has to conventional deadlift.

Likewise…

No one has to low-bar squat or squat with a symmetrical stance.

No one has to bench press or bench press with an aggressive lumbar arch.

And no one has to start watching Severence on Apple TV. Except, yes you do.

I’d argue a “good” coach understands and respects that everyone is different, and that he or she will be humble enough to put their own personal biases in their back pocket and appreciate there is no ONE way to perform any exercise.

Cater the lift to the lifter, and not vice versa.

- Or tall kneeling band resisted DB bicep curls off a BOSU ball (blindfolded).

- If someone is unable to maintain a good spine position during their deadlift but CAN keep a good spine position in the Rockback test, the culprit is, likely, NOT a mobility issue. It’s most likely either the novelty of the exercise (they need more practice) or lack of motor control/stability. Conversely, if someone is unable to control ROM during their deadlift and you see the same faulty pattern on the Rockback test, you can ascertain it’s likely a mobility or structural issue.