We all know that squats are a staple movement that span the gauntlet when it comes to helping people get stronger, leaner, and faster.

Blah, blah, blabbidy, blah.

That’s all well and good. But lets be honest.

Squats also help build bodacious bottoms.

There’s a reason why no one has ever written a song titled “Flat Bottomed Girls” or “I Like Average-Sized Butts.”

We like our derrieres fat and big, baby!

Alas, this article isn’t about the human form, appreciating the backside, and how squats help build bottoms.

No, this article is about something else entirely.

How to Build the Squat FROM THE BOTTOM

Dean Somerset and I spent this past weekend up in Kitchener, Ontario (<– that’s in Canada) just outside Toronto co-teaching our Complete Hip and Shoulder Workshop.

Note: you can check out to see if we’re coming to your neck of the woods HERE.

One of the main bullet points Dean and I hit on was squat patterning and how coaches and personal trainers can go about cleaning up their athlete’s or client’s squat technique.

Or, better yet: demonstrate to them some semblance of success.

Just so we’re clear: I think the squat is a basic movement pattern that everyone should be able to perform. I’m not insinuating that everyone should be able to walk into a gym on day #1 and drop it like it’s hot into a clean, deep squat and/or be able to load it to a significant degree.

Not everyone can (or should) squat deep. I’ve written on the topic several times, and for those interested you can go HERE and HERE.

That said, it is a movement pattern that’s important and one that can help offset many postural weaknesses, imbalances, not to mention more colloquial goals like athletic performance and aesthetics.

Assessment

Squat assessment is a crucial component to figuring out what’s the right “fit” or approach for each individual.

I can’t stress this enough: Not everyone is meant to squat to ass-to-grass on day one. Not everyone has the anatomy or hip structure to do it!

But it’s also important to figure WHY someone can’t squat to depth? Is it a mobility issue (which many are quick to gravitate towards) or a stability issue?

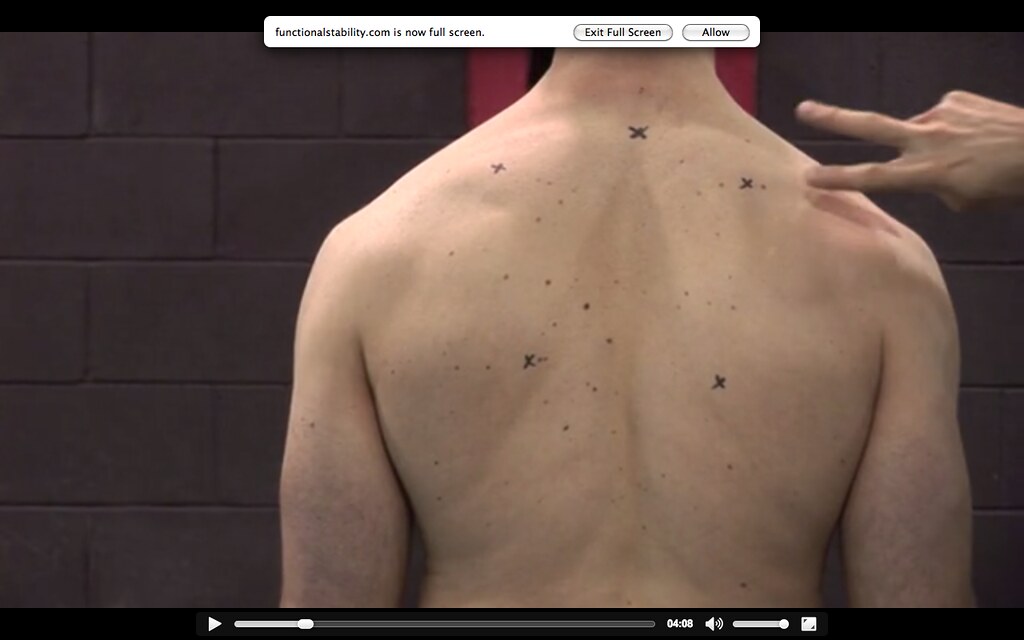

Digging deeper on the mobility-stability conundrum, Dean hit on a few important points this past weekend in trying to differentiate what mechanism(s) prevent someone from A) squatting deeper than that think they can squat and B) squatting with a better, more efficient pattern.

It’s a concept I’ve used myself with my own athletes and clients, but Dean did a really great job at peeling back the onion and helping the attendees better understand where they should focus their efforts.

Is it a Structural Issue?

Say someone makes the Tin Man look hyper-mobile when they squat. No matter what they do or how they position themselves, they just can’t seem to squat to an appreciable depth.

Most trainers and coaches would chalk it up to something lame like “tight hip flexors” or lack of hip mobility (which certainly could be the case), and revert to any litany of drills to improve either of the two.

This could very well be the correct anecdote, but I do feel it’s an often simplified and overused approach. I can’t tell you how many coaches have taken this route only to end up barking up the wrong tree.

It’s imperative to dig a little deeper.

Structural issue(s) = bony growth (FAI?), bone spur, and/or geometry of the hip joint itself.

As a trainer or coach you’re not diagnosing anything, and unless you’re Superman1 and have X-ray vision you’re more or less speculating anyways.

Assuming you have the knowledge base and are comfortable doing so, you can ascertain of what each person’s (general) anatomy is telling you by using a hip scour.

Supine (Passive): Have an individual lay on his or her’s back and bring knee into hip flexion. Is it uncomfortable or do they feel any pinching at or near the hip joint? If so, abduct the hip. Does the pinching go away? Do they gain more hip flexion?

This can speak to what their ideal squat-stance width should be.

You can also check hip internal/external rotation. Do they have more or less ROM in either direction? This could speak to more retroversion/anteversion of the acetabulum itself.

In general: those with an anteverted acetabulum (more than enough IR) are going to have crazy amounts of hip flexion. These are people are the ones who can squat ass-to-grass without blinking an eye. Of course, whether or not they can control that ROM is another story.

Conversely, those with a retroverted acetabulum (more ER) may struggle with hip flexion (bone hits bone earlier) and will likely never live up the all the internet trolls’ expectations regarding squat depth.

They’ll likely dominate hip extension ROM, however.2

Supine (Active): You can also have someone test their hip flexion ROM actively (meaning, they’re the ones doing the work). The key here, however, is making sure they use their hip flexors to actively “pull” their knees towards their chest.

Can they do it? Any restrictions?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k3TI-GJNl9w

Prone/Quadruped: Another “screen” to add is in the quadruped position where, again, the person is more stable.

Here you’re checking to see at what point do they lose control of lumbar positioning?

Some people, due to their anatomy, and despite 698 coaching cues being tossed their way, will lose positioning before they hit 90 degrees of hip flexion. You can be the most well-intentioned coach in the world, but unless you’re Professor Dumbledore you’re never going to be able to fit a square peg into a round hole.

So, you work with what’s presented to you. This person will need to squat at or above parallel.

I’m fairly certain the Earth will still continue to spin.

However, what you’ll often find is that they’re able to get into what would be equivalent to a “deep squat” position. Further, if you have them dip down and extend their arms above their head it’s akin to the same position as an overhead squat.

If they’re able to assume this position, it’s a safe bet (although not entirely exclusive) they it’s not a structural issue that’s preventing them from assuming a deep(er) and “clean” squat pattern.

All of it’s information – which may or may not stick – but it’s information nonetheless. And it’ll all help guide you as a coach to figure out what’s most suitable approach for your athletes and clients.

When assessing someone’s active squat pattern they may present as a walking ball of fail and demonstrate a whole host of compensation patterns. This is where some fitness professionals are quick to jump on the “it’s a mobility issue” bandwagon.

Taking the time to perform a more thorough screen (like the ones suggested above), though, is an excellent way to glean whether or not that is indeed accurate.

Squat From the Bottom

Lets assume you figured out it’s NOT a structural issue. You assess/screen someone in the supine/prone/quadruped positions and find they’re able to exhibit a passable squat pattern.

Yet, when they stand up and attempt to squat they resemble a stack of crashing Jenga pieces.

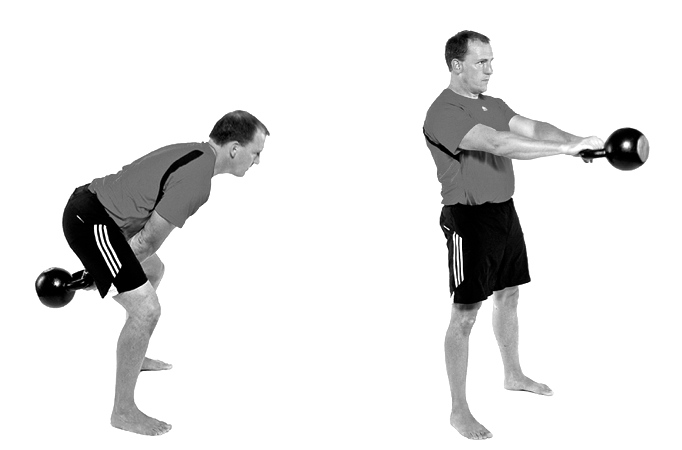

One of the best strategies I’ve found to help address this is to teach/re-groove the squat pattern FROM THE BOTTOM. Basically, start in the end position.

It helps to build context and confidence. In addition, it engrains the CNS to inform the brain “dude/dudette, relax, we got this!”

Assisted Squat Patterning

If I’m working with someone in person, I’ll hold my hands out in front of me (palms up), ask them to place their hands on top of mine (palms down), assume a squat stance, and “groove” their squat pattern (sit back with the hips, push the knees out), and “pull” themselves down into the bottom position of the squat.

I’ll then have them let go, hold that position for a good 3-5 second count, and then stand back up. We start them where we want them to finish. As a result this BOTTOMS-UP approach helps groove technique, but more importantly helps improve people’s confidence at sitting in the hole.

Some other variations you can use:

Squat Walk Down

Suspension Trainer Assist

Have someone grab the side of a squat or power rack (or use a suspension trainer – TRX, Jungle Gym) and use as much assistance as they need in order to get into the bottom position.

Note: Make sure they maintain a good back position.

Once they get into a position they feel they can control and “own,” have him or her let go and hold that position for a 3-5s count.

Then, stand up.

Have them repeat for several repetitions.

You’ll often find that after a few reps things start to click.

Boom

When it comes to squatting, not everyone should be held to the same standard.

- Perform the screens mentioned above. Do your job.

- Figure out what the best “fit” is for each person – depth, stance width, foot placement, etc.

- Use pattern assistance if necessary. Start from the bottom. Build success into people’s training.

Either approach you use – whether it’s partner assisted or with external assistance (rack, TRX) – the main advantage is that it forces anterior core engagement, which in turn helps improve stability, which in turn improves motor control, which in turn makes people into rock stars.

Except without the fame, money, and glory. And amphetamines.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches.