Today’s guest post comes courtesy of trainer, writer, and guy I hate because he is waaaaaaay too good looking, Michael Gregory.

Michael wrote an excellent post on nutrient timing for my site last year which you can check out HERE. He’s back again discussing an important topic: “reframing” injury and how to use (more) training to aid recovery.

Warning: Avengers: End Game spoilers ahead.

But come on: It’s been three weeks for crying out loud. If you haven’t seen it by now it’s your fault.

The Road to Recovery Is Paved With More Training

Let’s talk about acute injuries in your clients: those accidents that leave a scar in the shape of a teddy bear.

“Oh! What a cute injury!”

Allow me to elaborate, for those of you who aren’t a fan of Dad jokes.

If you hurt yourself, the best recovery plan you can follow includes continuing to train and actually treating the injury as if it is less egregious than it may actually be.

I’m not suggesting that you act as if nothing happened, but I am suggesting that you only adjust your training as much as you have to in order to work around the pain.

As a coach, you aren’t a doctor, so don’t act like one. You are, however, in the chain of recovery, and may be the only fitness professional around when an injury first occurs.

Know your role Snoop Lion

How you react matters to your client more than you realize.

The Assumption Is You Know What You’re Doing

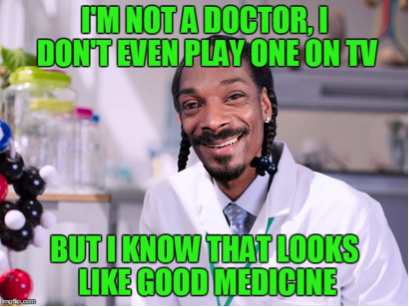

You’re a shit hot programmer that doesn’t plan anything your client isn’t ready for because you follow the principle of progressive overload.

One-rep maxes are not a spontaneous event that you perform when the sunset is a particularly auspicious color. They are planned for and prepared for, for weeks or even months in advance.

Because you program smartly, you know that any injury a client sustains under your care isn’t going to be a career ender.

It’s simply a kiss from the weightlifting gods that initiates them into the barbell illuminati.

If you train hard you will have battle wounds. That being the case, it’s time you learn how to get your clients past their injuries in the most economical way possible.

The Biopsychosocial Model of Pain for Acute Injuries

This framework comes from Dr. Austin Baraki over at Barbell Medicine. It applies on some level to every injury you or a client may sustain.

This entire process is about facilitating the best environment for healing. That means not freaking out and quitting, but rather, changing training only as much as is needed.

Step 1: Reassure AKA “Don’t freak out.”

Even if someone’s eye is hanging out of their skull, the best thing you can do is keep your cool. The power of positive thought is a hot topic these days.

There’s guys healing broken spines with just their minds, supposedly.

Even if those stories are only 10% accurate the power of the placebo effect is a wildy useful tool to have on your side. Keeping your cool and addressing unhelpful thoughts and fears are the first things you can to do to help your clients harness the effects of the placebo.

This is the psychosocial aspect of the model. It is the most important to get right the first time. Poisonous thoughts are really hard to uproot once they’ve been planted.

This whole step is the opposite of what my Junior Varsity football coach did to me and my relationship with the 2-plate bench press.

He told me I’d never be able to bench 225 with my long-ass arms unless I weighed 300+ pounds and the gravitational pull of the moon was twice its normal strength.

(Brief aside: Of course, the world’s weather and tidal patterns would be thrown into absolute chaos if all of a sudden the moon was twice as strong. So the joke’s on Coach J, because we’d all be dead before I could even make it to the gym. Try to remain calm after that sick burn.)

Regardless, I struggled for years with that negative reinforcement (nocebo effect) in my head. I could rep out 205 for sets of 5 but as soon as that second plate went on the bar “it was too heavy.”

Step 2: Assess the Situation

Like a good cub scout that just stumbled onto the remains of a deer that had been hit by a car, you’ve got to get your bearings.

Should you help it?

Put it out of its misery?

Add it to your Instagram story?

He already knows he messed up. Overreacting isn’t going to help the situation.

Start by asking the trainee what they were attempting and what they felt.

Remember, poker face: don’t let ‘em see you wince.

This is the first two “O’s” of the OODA loop, something that fighter pilots and military tacticians love to reference. Observe and Orient to the situation. (DA is Decide and Act, but you have to orient first).

No need to jump to any reactions here or start calling people lower life forms.

Be a professional.

Step 3: Move Forward by Reintroducing Movement in a Non-Threatening Context

Your special snowflake of a client is down, but not melted. You can still fix this and get them back to lifting heavy and kicking in doors faster than you can say “rubber baby buggy bumpers”.

Arnold said it first.

Your goal is to work your way backwards from the exercise that caused the injury in as short a distance as possible.

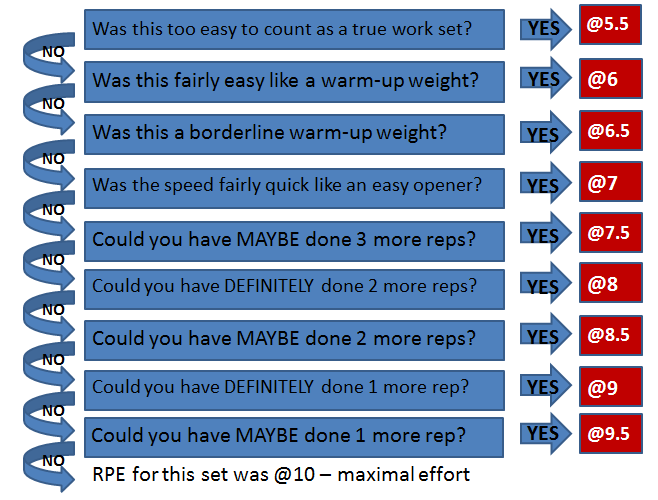

Start by asking these questions:

1st Question: Load. Is there a weight you can use that does not hurt?

If you can just reduce the weight of the exercise and the client no longer feels pain or discomfort then… do that.

If your client felt a “tweak” (technical term) in their mid-back while deadlifting, deadlift day isn’t over. Just take some weight off the bar. If it still hurts with 135, use the bar.

If it still hurts with the bar, use a PVC pipe.

The goal here is to show your client that the movement isn’t inherently dangerous at all weights.

2nd Question: Range of Motion. Where does it hurt?

If your client is still in pain conducting the movement with only their bodyweight, the next thing to adjust is range of motion.

In deadlifting, for example, if their pain is in the first two inches off the floor, elevate the bar until you are out of the danger zone.

No, this isn’t perfect form, for you deadlift sticklers out there, but your client isn’t going to be doing deadlifts from the rack or with the high handles on the trap bar forever. Pretty much as soon as you adjust the range of motion of a movement you should be planning for a progression to get the trainee back to the full movement.

If you haven’t seen it, consider this your warning.

Secondly, who the fudge decided what “full range of motion” is for any given exercise?

If your client isn’t a competitive lifter, it doesn’t actually matter.

I promise you won’t cause a rift in the space-time continuum resulting in an alternate timeline where Thanos succeeds in destroying half of all life in the universe and it stays that way. (Okay, that’s not really a spoiler so much as conjecture. Hey, spoiler warnings entice the reader to finish the article).

3rd Question (well, statement): Exercise Selection. If decreasing the weight and range of motion still results in pain, work your way backwards down the line of exercise specificity.

Only now should you be thinking about changing up the exercise entirely. This is assuming that you chose the initial exercise because it is the one which most completely trains you client to achieve their specified goal. If you just chose the exercise because it makes the vein in your biceps pop when you apply the Clarendon filter on Instagram I ask you the following question. How did you get this far in this article?

As an example, let’s say you were doing conventional deadlifts with your client. In my mind, the regression looks something like this:

- Conventional deadlift

- Snatch grip deadlift

- Sumo deadlift

- Straight leg deadlift

- Romanian deadlift

- Trap bar deadlifts

- Rack pulls

- Dumbbell deadlift variations

- Single-leg DB deadlift variations

- Single-arm DB deadlift variations

- Single-arm single-leg DB deadlift variations

- Good mornings

- Cable pull-throughs

- Hip thrusts

Okay, I digressed quite far there, but I think you get the point.

There are lots of exercises you can try with your client to teach them that they are not only not broken, but in fact still strong even with pain.

There is no excuse for the countless number of trainees doing leg presses and camping out on the stationary bike in the name of recovery.

Training is recovery.

It’s All Really Just Reassurance

This entire process of managing acute injuries is really just reassuring people that they aren’t fragile.

Some of our fellow humans, some of them your clients, have spent their entire lives avoiding pain at all costs. As a result, they’ve never had to learn how to overcome true adversity. By teaching this process to your clients, you are giving them the gift of self-reliance.

Resiliency is something most trainees are looking to build, mostly in the context of making their muscles more resilient. As far as I’m concerned, tenacity, fortitude, resilience, and mental toughness are all muscles. Each and every one of those is embedded in this process, and they are all made stronger every time someone learns to overcome something you or the barbell throws their way in the weightroom.

Does that tempt you to injure your clients on purpose now so that you can teach them about mental toughness?

Don’t do it.

But do be prepared to react calmly and with precision when accidents happen.

About the Author

Michael is a USMC veteran, strength coach, amateur surfer, and semi-professional mushroom connoisseur. As an intelligence officer and MCMAP instructor Michael spent the majority of his military career in the Pacific theater of operations.

Michael is a USMC veteran, strength coach, amateur surfer, and semi-professional mushroom connoisseur. As an intelligence officer and MCMAP instructor Michael spent the majority of his military career in the Pacific theater of operations.

He now lives in Bali where he writes, trains, and has had multiple near-death experiences in surf that is much too heavy for him.

For more by Michael check out his Instagram, Facebook, or his website www.composurefitness.com.

better at your sport, not to set the world record in powerlifting or weight lifting (unless those are your sports). Check your ego at the door.

better at your sport, not to set the world record in powerlifting or weight lifting (unless those are your sports). Check your ego at the door. 1. The first thing I’d want parents and athletes to understand about strength training is that it doesn’t need to be (and almost always shouldn’t be) something that completely exhausts the athlete. A ton of productive work can be accomplished while still feeling pretty fresh after.

1. The first thing I’d want parents and athletes to understand about strength training is that it doesn’t need to be (and almost always shouldn’t be) something that completely exhausts the athlete. A ton of productive work can be accomplished while still feeling pretty fresh after. qualities such as strength and speed to increase the robustness of the athlete’s skills. The goal in the weight room is to create a better all-around athlete who is able to express that athleticism on the field.

qualities such as strength and speed to increase the robustness of the athlete’s skills. The goal in the weight room is to create a better all-around athlete who is able to express that athleticism on the field. 1. The idea of “Sport Specific training” is a hoax – Athletes and parents need to understand that our jobs as strength and conditioning coaches is to make better athletes (through strength, speed, and power gains along with injury reduction protocols).

1. The idea of “Sport Specific training” is a hoax – Athletes and parents need to understand that our jobs as strength and conditioning coaches is to make better athletes (through strength, speed, and power gains along with injury reduction protocols).

1. The real impetus behind this discussion, for me, was that I really want athletes and their parents to understand that getting ready for a particular season takes more than two weeks.

1. The real impetus behind this discussion, for me, was that I really want athletes and their parents to understand that getting ready for a particular season takes more than two weeks.