In case you missed it, last week I shared a few thoughts on deadlifting. You can check out part one HERE.

In it, rather than regurgitate the same ol’ obvious things most people who write about deadlifts regurgitate (don’t round your back!, good deadlifters don’t “jerk” the bar off the ground, 2+2 = 4, water is wet, Kate Upton is hot, my cat is the cutest cat in the world) I opted to highlight a few things I feel most lifters overlook or aren’t aware of in the first place.

Things like:

– how the lats play a key role in pulling big weight off the floor.

– how to engage the lats more optimally.

– how paying closer attention to your setup may result in better performance.

– and what it really means to pull the slack out of the bar. I promise, despite the nefarious connotation, the explanation is completely PG rated.

– But seriously, my cat is off the charts cute.

As promised I wanted to continue my stream of thought and hit on a few more “habits” of highly effective deadlifters.

4. Think of 315 as 135.

Chad Wesley Smith of Juggernaut Strength hammered this point home a few weekends ago during a workshop he put on here in Boston at CrossFit Southie.

To paraphrase: You can’t be intimidated by the weight. You need to approach the bar on every set and show it who’s boss. Every time.

Like this monster.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4jO21-a2W0

Setting a little expectation management, though, if you’re training in a commercial gym and acting like this before a set of 225, you’re an a-hole. Lets calm down a little bit and put down the ammonia packets mmmm kay?

Many trainees will attack a lighter load and then turn into Bambi once the barbell hits a certain weight or threshold. Lighter loads will generally go up faster than heavier loads…..duh, I get it. However, this point does speak to something larger, and something that’s a bit more psychological in nature.

If you approach the barbell with a defeatist attitude – oh shit, oh shit, oh shit – before you even attempt the lift, how will you ever expect to improve, much less lift appreciable loads?

If you watch good (effective) deadlifters you’ll notice that every set looks the same. Regardless of whether there’s 135 lbs on the bar, 315, or 600 lbs, everything from the set up to the execution of the lift is exactly the same.

Which is why, flipping the coin, we could also make the argument that 135 lbs should be treated like 315. Getting good at deadlifting requires attention to detail and treating every set the same. Even the lights ones.

5. Don’t Just Think “Up.” Think “Back.”

The deadlift is nothing more than bending over and picking up a barbell off the ground, right?

Well, yes….but it’s a bit more complicated than that.

Many will view the deadlift as a pure up and down movement. Meaning, the barbell itself will move in a path that’s literally straight up and down.

Ehhhhhhhhhhhh, wrong.

23.7% wrong, at any rate (<—- trust me it’s science).

The deadlift is actually much more of a horizontal movement than people give it credit for. To quote my good friend, Dean Somerset:

“Deadlift drive comes from the hips when you start in flexion and move into extension. In other words, deadlift drive comes through hip drive. Driving your hips forward, coupled with vertical shins and a stable core, causes the torso to stand up vertically, pulling the weight with it.”

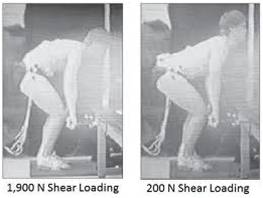

When people get into the mindset that deadlifitng is more of vertical movement they’ll often resort to initiating and finishing the movement with their lower back rather than their hips. Which, as you can guess, leads to some wonky habits of the rounded back nature (which we’d like to avoid as much as possible).

A cue I like to use to help initiate more of a horizontal vector is to tell people to think about “driving their sternum to the back wall.”

When they initiate the pull, they shouldn’t think up but rather……..BACK!

It sounds weird, but I like to describe this phenomenon by telling people that if they do it right – and think about pulling their sternum back – that they’d fall backwards if they decided to let go of the bar.

6. Deadlifts Don’t ALWAYS Need to be Max Effort, I’m Going to Shit My Spleen, Heavy.

Yes, you’ll need to train with max effort loads in order to improve your deadlift. To quote Ronnie Coleman, you’ll need to “lift some heavy ass weight.”

That’s pretty much a given.

But you DO NOT need to do it all the freakin time.

This is another point that Chad Wesley Smith touched on a few weeks ago. To paraphrase him (again): “I could care less about gym PRs. I want to PR when it counts.”

Understandably, most of the people reading this post aren’t competitive powerlifters like Chad, so how he trains and prepares (and peaks for a meet) is going to be drastically different from most of us.

But the message still resonates and reigns true for most trainees. You don’t need to train balls to the wall 100% of the time.

This is a tough pill to swallow for many people, especially in the shadow of CrossFit where training all out, to the point of exhaustion is not only encouraged but accepted as normal.

Don’t get me wrong: I LOVE when people train hard, and I think CrossFit has done some good in terms of getting more people excited to not run a treadmill.

However it’s also set a dangerous precedent in brainwashing people into thinking that a workout or training session is pointless if you don’t set a PR or come close to passing out.

NOTE: this doesn’t apply to every box or every Crossfit coach. So relax guy who’s inevitably going to shoot me an email saying I’m nothing but a CrossFit hater.

1. I actually have written a fair amount praising CrossFit. Like HERE.

2. I also workout at a CrossFit 1-2x per week – albeit during “off” hours when I have the place to myself along with the other coaches.

3. Shut up.

More often than you think, training with SUB-maximal weight (60-85%) is going to be the best approach for most people, most of the time. Not only does it allow for ample opportunity to focus on and work on technique, but it also allows people to train the deadlift more often.

The best way to get better at deadlifitng is to deadlift. A lot.

If you’re someone who constantly trains with max-effort loads this is going to be hard to do because 1) you’re going to beat up your joints 2) you’ll fry your CNS and 3) this requires more recovery time.

Not every training session requires you to hate life. This is especially true when it comes to improving your deadlift. QUALITY reps are the key. Oh, this is weird…..it just so happens I have a deadlift specialization program that follows this mantra to a “t.”

You should check it out.

Pick Things Up

7. Pull & Push

The deadlift is a pulling dominant movement. But it also involves a fair amount of pushing.

Yep you heard me right, pushing.

Think of it like this: in order to pull an ungodly amount of weight off the floor (or for those less interested in ungodly amounts, a boatload or shit-ton) you need to generate a lot of force into the ground and push yourself away.

I’ve heard this best described as “trying to leave your heel print into the ground.”

It’s a subtle cue, but it works wonders and it’s something that effective deadlifters keep in the back of their mind all the time.

And there you have it. While not an exhaustive list of habits, I do feel the one’s highlighted in both parts of this article will help many of you reading dominate your deadlifts moving forward.

Got any of your own habits to share? Chime in below.