Last week my good friend and author of Day by Day: The Personal Trainer’s Blueprint to Achieving Ultimate Success, Kevin Mullins, wrote an introduction of sorts to the state of “corrective exercise” in the fitness industry.

To summate: Stop it. Just stop. People still need to train in order to get better.1

Today, in Part I, Kevin peels back the onion on the shoulder.

Grab a cup of coffee.

This is good.

Shoulders, Yo

Excellent strength coach, and outstanding Canadian, Dean Somerset once stated in an internet post, or maybe it was a blog, “there is always a cost of doing business.” He meant it as a point of emphasis when talking about the various effects of training programs and specific exercises. But he also could have extrapolated it outwards to reflect the stresses of our daily lives.

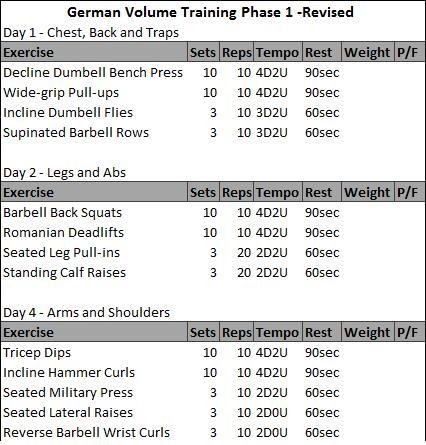

Poor posture while seated for twelve hours is going to have a cost associated with it just as German volume training.

Note From TG: OMG, German Volume Training brings back the worst memories. I don’t know which was worse: getting kicked on the balls or GVT?

For this reason, the fitness industry has made a major shift towards corrective exercises. Once seen as the tools of progressive physical therapists – these mobility, stability, and integrated exercises have become critical elements in training programs for elite athletes, nimble geriatrics, and the average Joe and Jane alike.

The growth of corrective modalities in conventional personal training is a good thing overall. However, as I pointed out in the introduction to this article series – HERE – there exists a very big downside to the obsession with movement perfection and body correction.

There needs to be a better way of correcting people’s movement flaws, overcoming their specific weaknesses, and getting them to a place where they can safely train hard. Far too many coaches are “under-training” their clients because they are investing too much time “correcting” things. At some point we need to get people training hard towards their actual goals.

Using Your Head For Their Shoulders

There may be no part of the body more susceptible to under-training than the shoulders. With multiple skeletal structures, a bunch of muscle attachments, and a relationship with the spine – there are a lot of reasons that someone wouldn’t be “allowed” to train hard with their shoulders.

Training them includes more than the traditional bodybuilding approach too.

The glenohumeral joint is involved in all upper body pushing and pulling motions as well as the specific isolation exercises that are popular in bodybuilding programs (such as lateral raises or chest flyes). The scapula and clavicle are too, but their positioning on the body also impacts movement such as the deadlift and squat.

Because of their high level of integration with every exercise we do, the shoulders are often the most banged up part of a client’s body. Our poor postures and ill-advised training programs aren’t helping us. Often the two compound each other and only worsen any dysfunction that exists.

Hence the need for correctives.

Really though, the shoulder itself is a bit of a miracle joint – with all the muscles that cross it, the fascia, the nerves, blood vessels, and obvious skeletal structures – it is amazing that it functions as well as it does.

But there can be a whole host of issues going on, or there can be just one. And that is what is most challenging about assessing and correcting shoulder dysfunctions.

- It could be as simple as improving someone’s ability to retract and depress their scapula, such as when someone’s posture isn’t where we’d like it.

- Or as complex as improving external rotation of the humerus while also stealing more extension from the thoracic spine and stability from the scapula during upward rotation and elevation, such as when a client wants to get better at pull-ups.

No matter how intense the problem is it is important that we as coaches keep our processes simple.

Removing the Restrictions

Yet, simple is not how most coaches approach shoulder health.

In fact, if you were to follow many of the conventional prescriptions that are floated through the industry, then you’d avoid many of the things that produce big results for your clients in favor of small correctives that make small changes. While some clients do need more intervention with these corrective methods – most simply need enough to create an opportunity for more intense training.

If you were to follow many of the guidelines that accompany something as notable as the Functional Movement Screen (the FMS), then many of your clients would not be allowed to press, or pull vertically, or load up abduction or adduction in the frontal or transverse planes until they were able to get a “2” on the shoulder mobility assessment.

While Gray Cook and Lee Burton did an incredible job creating a screening tool that helps coaches discover dysfunction and lack of movement prowess – they also created a system that is preventing a lot of clients from actually getting better.

Note From TG: For anyone interested (I.e., everyone) I wrote about my experience taking the FMS and what I took from it HERE.

The protective measures and governing principles of systems put the fear of God in personal trainers who use them. Many are afraid of loading anything until they see a two on the scoreboard. It is a steady dose of low intensity or no intensity correctives until that day.

Which is where the problem with corrective exercises starts:

Low to no intensity corrective exercises aren’t why clients improve over time. Instead, it is the strengthening exercises that come after these correctives that matter most.

If we are to improve how we utilize corrective exercises in our programs, then we must be willing to accept that what we now know isn’t perfect. We must be willing to entertain the idea that there is a better way of doing business. It is this exact mentality that drives innovation in technology.

It will drive innovation in fitness if we let it.

—-

(It is important to pause here and make a statement – this article is not meant to treat, diagnose, or prescribe methods or modalities for someone who is dealing with diagnosed injury or dysfunction in their shoulders. Traumatic injuries, conditions such as frozen shoulder, cervical kyphosis, and others require a finer touch from qualified medical professionals.)

If Not This, Then What?

Corrective exercises are like the bore that drills tunnels in the side of a mountain. They create the space for the construction to take place, but they aren’t the construction. You wouldn’t want to drive through a tunnel that hasn’t been reinforced with steel supports and millions of pounds of concrete, so why do you think that corrective exercises are enough to create a finished product in fitness?

The mobility and stability exercises that we define as “correctives” simply create the space for more optimal change to take place. They create the opportunity for well-selected strength exercises to change the tissues for the better.

For shoulder health we find that the classic approach of wall-angels, thoracic roll-overs, and cat-cows are simply creating the opening for which exercises like loaded carries, supinated pulldowns, and banded retractions fill with strength and stability. Our goal needs to be to do enough to get to the exercises that stimulate adaptation and create positive change; in the shoulders and in the rest of the client’s body.

Our responsibility as trainers is to help our clients overcome dysfunctions and improve their movement quality – sure. But our job also implies that we help our clients burn calories, build muscle, and come just short of conquering the universe.

Before diving into the actual corrective exercises that will open the gates for us to train with the intensity our client’s want and need, let’s ensure that everyone reading is on the same page on the anatomy and physiology of the shoulder joint.

The Basic Anatomy and Physiology – Skeletal

When looking at the shoulder joint you are presented with three major bones: the clavicle, the scapula, and the humerus.

- The clavicle (or collarbone) is the most stationary of all of these structures, but its lateral aspect does elevate and depress in reaction to movements of the other bones. The humerus, the upper arm bone, is designed for external and internal rotation within the socket – known as the glenohumeral joint.

- The humerus can move through flexion, extension, abduction and adduction, and horizontal abduction and adduction by rotating around the glenohumeral joint in each of the three planes (sagittal, frontal, transverse). These movements are aided by the function of the scapula.

- The scapula (or shoulder blade) is the large bone in the back of the body. It is capable of six motions: elevation, depression, upward rotation, downward rotation, protraction, and retraction. These movements are also correlated to the three planes of motion too – sagittal, frontal, and transverse respectively.

The spine is also involved in shoulder mobility and stability is often left out when looking at function. We will explore this relationship in the next section when we begin looking at how core function can impact shoulder mobility as well as how thoracic extension is necessary for optimal function of the shoulder joint.

The Basic Anatomy and Physiology – Muscular

The human shoulder functions as incredibly as it does because of the incredible number of muscles that are involved. Some control the humerus, others control the scapula, and others control the spine.

Most of these muscles are found in the back.

When looking at the muscles that contract at the shoulder, we must separate the muscles that control the external rotation and internal rotation of the humerus from the muscles that create the six motions of the scapula. While some muscles share functions – it is important to identify its primary action and what it acts upon in order to better understand how the shoulder wants to function.

The four muscles of the rotator cuff are most responsible for the external and internal rotation capacity of the humerus.

- There is evidence to support that the triceps are involved in external rotation, especially under load (just turn your arm around as far as you can right now, and you’ll feel the lateral head of the triceps contract). Therefore, the triceps join the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor as external rotators of the humerus.

- With that claim we can also ascertain that the biceps and pectoralis group are involved to some degree in internal rotation (although there is significantly less IR available at the shoulder joint). The subscapularis is the internal rotator of the cuff.

When examining the muscles that move the scapula, we are simply looking at the muscles of the upper back; the lats, teres major, rhomboids, trapezius, levator scapulae, the serratus and the three external rotators of the cuff. Each of these muscles have specific functions on pieces of paper, but it is imperative as coaches that we realize that most exercises performed in a gym setting involve more than just one of these muscles doing one of these functions.

It is easy to point at the traps and say “oh, they are elevators and contribute to upward rotation.” It is less easy being able to look at a flawed motion and know exactly what is wrong:

For example, many coaches will point at someone having issues with retraction and think “ah, the upper traps are overactive and the teres major/minor need strengthening.” They could be right and probably are in a population of people who sit with rounded thoracic spines and internally rotated shoulders.

Add in forward neck and shrugged shoulders and this “diagnosis” seems spot on.

However, getting just the teres group to fire without activating the infraspinatus or supraspinatus is nearly impossible in a traditional training setting. Getting someone to stay out of their upper traps sounds like a great coaching cue, but that requires getting them to fire the muscles that contribute to scapular depression; the lower traps, pectoralis minor, and latissimus dorsi at the same time – something most clients (or you) can’t do consciously.

In fact, a lot of scapular depression comes from the ability to put the thoracic spine into extension. Doing so involves activation the lowest fibers of the traps, the lats, the upper abdominals, and a whole host of muscles that are so deep and connected to the individual vertebrae that considering them in training is pointless.

When these muscles contract and thoracic extension takes place, you find that the scapula better slide into the depressed position.

The Core Connection

Yet, thoracic control isn’t completely isolated either.

It is very hard to contract the thoracic muscles without some level of core control. In this instance, the core includes the anterior muscles of the core that we know (rectus and transverse abdominals, internal and external obliques, and Psoas Major.

It also includes the muscles of the posterior core: the quadratus lumborum and the erector spinae.

Conscious contraction of these muscles allows for the core to hold tension, which better stabilizes the lumbar spine, which better allows the thoracic spine to go into extension, which better allows the scapula to depress, which better allows the humerus to externally rotate. As you can see, everything is connected, which is why we can’t use such generic correctives to solve complex problems.

A Less Important Factor?

You’ll notice that we haven’t yet mentioned the deltoid – the most known shoulder muscle. For all the attention it gets in bodybuilding circles its function is not as critical to shoulder function as you’d believe. The anterior fibers assist in internal rotation and drive flexion of the arm while the posterior fibers aid in external rotation and initiate horizontal abduction. The lateral fibers function to create abduction of the arm in the frontal plane.

From a corrective standpoint, it is very rarely an issue with the deltoid that proves to be the problem. In fact, it is often the overdevelopment of the deltoids and upper traps and underdevelopment of the rotator cuff muscles that create impingement issues in dedicated lifters. Great corrective exercises keep the deltoids involved and avoid shutting them out.

The Hidden Gem

In recent years we’ve come to learn that the fascia in our bodies is more than just a covering and more than just extra tissue that gets cut through in surgery. It is a living tissue that is involved in our function on a day by day and minute by minute basis.

In fact, research from Michol Dalcourt and the team at the Institute of Motion have proven that the fascia can communicate information across the body faster than any muscle tissue. Its ability to compress and expand is crucial for athletic development.

Unfortunately, many fitness professionals see it as tissue that is addressed with foam rollers, lacrosse balls, and other release methods. This isn’t wrong of course as these implements can do well to increase blood flow, increase hydration of the fascia, and improve mobility of the joint in question. However, we can also train our fascia just as we train our muscles. We must look to incorporate the variety of slings that Thomas Meyer’s discusses in his text Anatomy Trains.

In our solutions section we’ll explore a few ways to do that to improve the function of the shoulders and truly correct any issues that exist.

But first, we must identify a few of the most common problems.

Common Problems

1) Desk Posture (UCS)

The most common problem that a client will present in regard to their shoulder health is the classic “desk posture”. The scapula sits in protraction and elevation while the humerus’ are internally rotated. This posture is held for eight, ten, and twelve hours a day. Over time the pectoralis muscles get tighter, the trapezius muscles lengthen, the muscles of the scapula and glenohumeral joint get weaker, and the client continues to worsen.

The most advanced form of this condition is known as Upper Cross Syndrome (UCS) – a severe condition of immobility that usually involves additional intervention with physical therapists, and sometimes, orthopedic surgeons. This posture often presents forward neck as a well – a dangerous condition of the cervical spine.

The treatment for individuals in this position is to correct their posture and work to move them in better retraction, depression, and external rotation. However, many of the common methods do not provide enough intensity to stimulate muscle growth or strength adaptations in the muscles of the upper back. It is crucial for trainers to invest time in building their clients upper backs and coaching optimal patterns if the corrective interventions are ever going to stick.

2) Poor Scapulohumeral rhythm

For many people the pain they experience in their pressing and pulling motions is a result of a poor pattern being present. Of course, there are others who have legitimate issues such as shoulder impingements, strained muscles of the rotator cuff, or overactive trapezius muscles that make doing certain movements nearly impossible. The rest though, simply need help reworking their patterns and an emphasis on strengthening the muscles that control those patterns.

The scapulohumeral rhythm refers to the quality of movement that occurs when we consider the scapula and glenohumeral joints interaction. People with great rhythms typically an exercise pain-free while people who lack control and patterning struggle to accomplish even the most basic tasks.

This topic is quite deep, but in short realize there is a relationship between the position of the humerus and where the scapula “should” be.

For example, in a traditional dumbbell overhead press the scapula should be upwardly rotating and elevating as the humerus adducts towards the midline at the top of the press. Many people will execute their press and have little to no movement out of their scapula, thus causing increased stress on tissues that shouldn’t need to encounter them.

3) Lack of External Rotation

One of the issues many clients face is the inability to rotate their humerus back. This is more than just the presence of too much internal rotation (such as with U.C.S.). The muscles responsible for external rotation of the shoulder are powerful muscles that also engage in the motions of the scapula. Lacking strength in these tissues can cause someone to become more internally rotated, but also makes it incredibly hard to achieve external rotation at the glenohumeral joint.

This matters for more than just mobility.

Popular exercises such as pull-ups require a person to own a certain amount of external rotation in order to execute the motion. So too does the overhead press. Lacking the ability to achieve optimal end range of E.R. makes both movements, and so many others, hard to accomplish.

It is important to understand that the exercises we use to improve external rotation put the humerus in a greater rotation than we would normally encounter in traditional lifting. But, this sort of work is necessary to strengthen and stimulate the muscles that create E.R. and maintain it in an isometric contraction (such as during a overhead press).

4) Weak Core and Poor Thoracic Extension

As stated earlier, the core and spine play a major role in whether the shoulders function optimally. A lot of lifters never develop optimal shoulder health because they create mobility by overextending their lumbar and thoracic spine to compensate. This is especially prevalent in ego lifters performing an overhead press with a massive amount of “layback”.

Lacking the ability to contract the anterior core and stabilize the lumbar spine makes it significantly harder for someone to master true thoracic extension. The ability to lift the ribs and extend the thoracic spine allows for better depression, retraction, and downward rotation of the scapula. These motions are direct opposites of the posture that many fall into as a result of upper cross syndrome or “desk posture”.

Strengthen the abdominal wall and muscles of the T-spine is imperative to optimizing shoulder function. Much like the foundation of a skyscraper must be firm and set underneath the construction, so too does our core and spine for our shoulders.

5) Weak Upper Back and Lack of Awareness

In a lot of cases, especially in individuals who do not regularly engage in an exercise plan, there is simply a lack of proprioception and strength in the muscles that control the scapula and glenohumeral joint. Often, there is nothing “wrong” with this population other than their lack of sensory awareness and force production capabilities.

Clients like this require more exposure to well-coached patterns and a progressively overloaded strength program that allows their muscles to adapt over time. It may be beneficial to use low intensity correctives to prime a specific pattern and create mobility in the joint prior to loading the muscles with traditional methods.

It is critical that we stop seeing all clients as wrecked when they are unable to perform a specific task. For many people, especially with something as obscure as the FMS, it is simply an unfamiliarity with their body and the demand you are placing upon them. Increase their exposure to well-coached exercise instead of trying to fix something that isn’t broken.

New Solutions

As we dive into the specific movements it is important for us to realize that these are just a few examples of great movements that can be used to strengthen and stabilize the shoulder joint. Some of these movements are common and others are painfully boring (in a sense that we aren’t shaking the Earth).

However, simplicity is often the fasted route to success.

A few of these movements are going to be outside the realm of normality for some coaches. Many traditional strength coaches would look at Animal Flow as a weird form of yoga and dancing, but it is that arena that brings the fascia into the fold. Other movements are simply manipulations of variables in the training arena, such as the angled press, that most people aren’t considering.

1) Dual Kneeling Band Pull Apart

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3rrHNDcVa9s

The band pull apart is nothing new.

However, adding in the kneeling position asks us to contract our core and our glutes – two major parts of our foundation. In doing so we can better extend our thoracic spine, which in turn allows for better retraction of the scapula.

2.1) The Full-House (2 Cables/3 Motions)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COSRT7nPTPc

This multi-pattern movement asks for retraction of the scapula, then retraction into downward rotation and depression (with external rotation of the humerus). Lastly, the overhead press asks for elevation, upward rotation, and forces the external rotators to fire hard to prevent the arms from collapsing forward of the line of gravity.

This sort of movement is incredible for grooving the scapulohumeral rhythm, improving upper back strength, and increasing external rotation of the humerus. It is quite the challenge and needs to be done extra light. Five pounds was the resistance in the videos.

2.2) Second View

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qt8ex9TL8GQ

3) External Rotated T, Y

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Juj1iYiJFE

A simple variation of traditional T and Y – this a movement that can be used to improve retraction of the scapula while strengthening the external rotators. It forces the trainee to own their humeral position and originate movement from the glenohumeral joint while remaining set onto stable scapula.

This exercise also promotes additional thoracic extension.

4) Angled Press

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVPsVXWXds0

Far too many people contraindicate the overhead push pattern when someone is dealing with shoulder dysfunction. If we were to listen to the FMS, no one who can’t get a two on the shoulder mobility exam should ever press overhead. Yet, tons of people can press pain-free without getting a two.

This exercise helps bridge the gap between overhead pressing and not. The slight angle (about 15 degrees) allows you to load up the deltoids a bit without creating a perfect opposition to gravity. The neutral grip, forward elbow, and emphasis on tempo allows us to focus on scapulohumeral rhythm. Use this as a primary exercise after preparing clients for their workouts. This will correct a lot of flaws so long as the movement remains pain free.

5) Supinated Pulldowns

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TbIy3pH0nlo

At first glance this looks like a standard, boring pulldown.

Yet, it is the dramatic emphasis on depression and elevation of the scapula that makes this one stand out. Far too many folks get on the pulldown and just start yanking on the bar to get their set done. The motion becomes about completion instead of optimization.

The supinated hand grip helps keep the humerus in a slightly more externally rotated position while also prevented much of the internal rotation that happens with heavy pronated pulldowns. The focus here is to emphasize absolute end ranges. Feel the scapula elevate while maintaining control and then drive them downwards into full depression at the bottom.

6) Simple Animal Flow (Beast Hold to Scorpion to Alternating Crab Reaches)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x27wT-nxUkg

A lot of you will look at this and wonder – why in the heck am I going to do all that flailing? Yet, animal flow is an incredible discipline that emphasizes loading of a lot of our passive structures – the fascia, the connective tissue, the skeletal system. Strengthening these things is imperative to the absolute realization of healthy shoulders. Specifically, the external rotation of the humerus in set crab position is a great tool to have in your arsenal.

7) BONUS: New Way to do Chest Flyes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hcRTVz4aWOE

Lastly, I want to share the new best way for you to execute chest flyes.

See, the chest flye is one of the most favorite exercises in bodybuilding culture. It causes a tremendous stretch of the pec fibers and can help the person doing them build the muscle they crave. Yet, there is a ridiculous amount of sheering force placed upon the shoulder joint when the dumbbells reach the bottom of a traditional flye.

So, instead of using dumbbells and pissing off your shoulders – integrate this band only variation. The key is to press out into the band for the entirety of the movement, thus keeping a high level of tension on the working muscles without stressing the shoulder joint against gravity. As you fatigue shorten the range and focus on the squeeze.

Putting It All Together

You can correct someone’s shoulders and move their fitness forward at the same time. Your job as a fitness professional is to drive your clients towards the results they want and the results they didn’t know they need. You can still use low intensity correctives in your programs, of course, but it is imperative to go forward understanding that they are simply a very small piece of a much larger puzzle. Your client, if they are to improve, must begin strengthening the muscles by training the appropriate patterns that address shoulder health.

Next: The Lower Back and Pelvis

In the next article we’ll explore the lumbar spine, pelvis, and anterior core and how we can better correct chronic low-level back pain, coach better hinge patterns, and improve our client’s ability to move with confidence.