Lifting Straps. Yes, No, Maybe So?

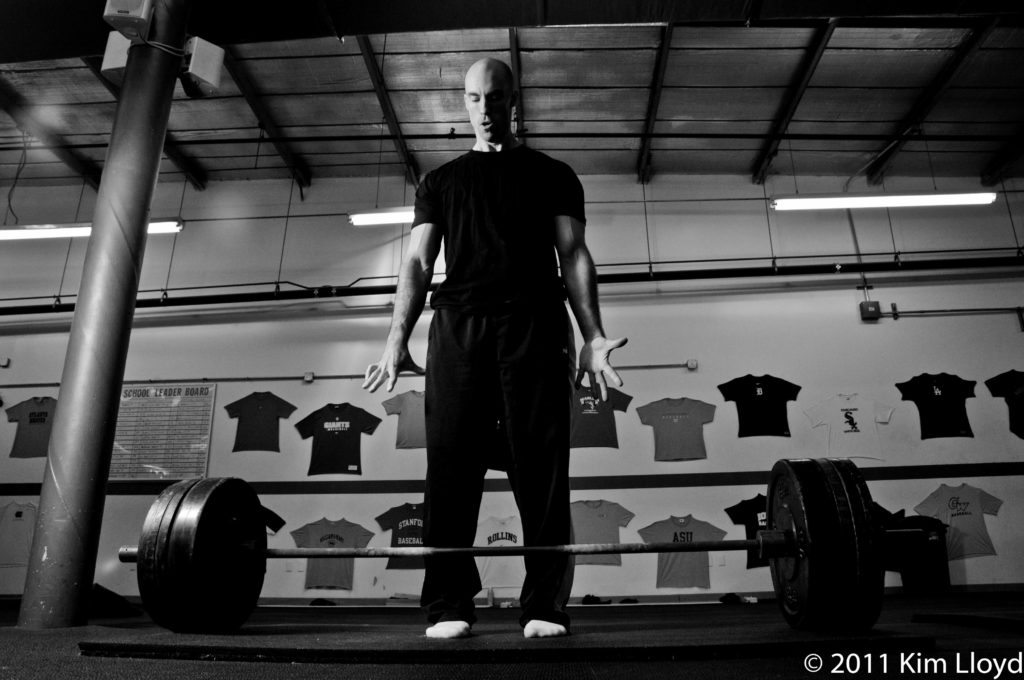

Starring at the barbell on the floor I couldn’t help but think to myself, “holy shit that’s a lot of weight.” Also, “I hope I don’t shit my spleen.”

The year: 2004. The place: Albany, NY, at some random Golds Gym.

I was visiting my sister and her family after a recent breakup with my then girlfriend and I decided to do what most guys would do when stuck in a vortex of rage, anger, sadness, and endless Julia Roberts movie marathons…

…I went to the gym to take my mind off of things.

This trip to the gym, however, would be different. I decided it was going to be the day.

No, not actually do some cardio.

I was going to deadlift 500 lbs for the first time.

I know this will surprise a lot of people when I say this, but I didn’t perform my first (real) deadlift until 2002 when I was 25 and still wet behind the ears with regards to my fitness career.

Mind you I had been lifting weights since I was 13, so it’s not like up until that point I had never seen a barbell.

It didn’t take long for me to become enamored with the deadlift. I loved that I was actually good at it, and I really loved how it made my body look and feel. It wasn’t long before I made it my mission to pull 500 lbs. It took me a little over a year to get there.1

Funnily enough, how I went about doing it was all sorts of contrarian compared to how I would approach the same task today.

Well, not 100% contrarian….but, you know, different.

1. I didn’t perform any traditional 90% work (working up to heavy singles). Instead I stayed in the 3-5 rep range, sometimes adding in some high(er) rep work for the hell of it. Whoever says you can’t improve your 1RM by working with sub-maximal weights is wrong.

As I like to remind my own clients today:

“you need to build a wider base with sub-maximal loads in order to reach higher peaks (in maximal strength).”

2. I didn’t use any special periodization scheme named after a Russian. I used good ol’ fashioned linear progression.

3. I didn’t rotate my movements every 2-3 weeks or follow some magical formula that had me incorporate the Mayan calendar. Nor did I perform some sort of dance to the deadlift gods every time there was a Lunar eclipse.

I performed the conventional deadlift almost exclusively.

Year round.

4. And maybe most blasphemous of all, I sometimes used wrist straps!!!

I know, I know…I didn’t want to be the one to break the news to you, but it’s true.

I believe straps should be used (sparingly) by pretty much everyone. For stark beginners it allows for more volume to be completed because grip becomes a limiting factor. For deadlifting terminators (I.e., really strong lifters) it also allows for more volume because grip becomes a limiting factor.

But this serves as a nice segue to a few question I receive almost without fail whenever I present:

Will using a mixed (under/over) grip when deadlifting cause any imbalances or is it dangerous?

Do you think straps should not be used during deadlifts?

First things first: Lets address the pink elephant in the room. I don’t feel utilizing a mixed grip is bad, and I do not think it’s dangerous.

This isn’t to say there aren’t some inherent risks involved.

But then again, every exercise has some degree of risk. I know a handful of people who have torn their biceps tendon – while deadlifting using a mixed grip. The supinated (underhand) side is almost always the culprit.

A LOT of people deadlift with a mixed grip, and A LOT of people never tear their bicep tendon. Much the same that a lot of people drive their cars and never get into an accident.

Watch any deadlift competition or powerlifitng meet and 99% of the lifters are pulling with a mixed grip. And the ones who aren’t are freaks of nature. They can probably also smell colors.

Pulling with a mixed grip allow someone to lift more weight as it prevents the bar from rolling in the hands. Sure we can also have a discussion on the efficacy of utilizing a hook grip, which is also an option.

I’m too wimpy and have never used the hook grip. If you use it I concede you’re tougher and much better than me.

Here’s My General Approach:

1. ALL warm-up/build-up sets are performed with a pronated (overhand grip).

2. ALL working sets are performed with a pronated grip until it becomes the limiting factor.

3. Once that occurs, I’ll then revert to a mixed grip….alternating back and forth with every subsequent set.

4. When performing max effort work, I’ll always choose my dominant grip, but I feel alternating grips with all other sets helps to “offset” any potential imbalances or injuries from happening.

Now, As Far As Straps

Despite what many may think, I don’t think it’s wrong or that you’re an awful human being or you’re breaking some kind of un-spoken Broscience rule if you use straps when you deadlift.

As I noted above, both ends of the deadlifting spectrum – beginners to Thanos – use straps. I think everyone can benefit from using them when it’s appropriate.

When I started deadlifting I occasionally used them because it allowed me to use heavier loads which 1) was awesome and 2) that’s pretty much it.

Straps allowed me to incorporate more progressive overload. My deadlift numbers increased. And I got yolked. Come at me Bro!

But I also understood that using straps was a crutch, and that if I really wanted to earn respect as a trainer and coach I had to, at some point, work my way up to a strapless pull. No one brags about their 1RM deadlift with straps in strength and conditioning circles. That’s amateur hour stuff for internet warriors to bicker over.

If you’re a competitive lifter, you can’t use straps in competition (outside of CrossFit, and maybe certain StrongMan events?)…so it makes sense to limit your use of straps in training.

If you’re not a competitive lifter, well then, who cares!?!

It’s just a matter of personal choice.

Note: If I am working with someone who’s had a previous bicep tendon or forearm injury, has elbow pain, or for some reason has a hard time supinating one or both arms, I’ll advocate that they use straps 100% of the time.

Offhandedly, straps do tend to slow people down which could be argued as a hinderance to performance. One mistake I see some trainees make with their setup is that they’ll bend over, grab the bar, and take way too long before they start their actual pull.

The logic is this: If you spend too much time at the bottom you’ll miss out on the stretch shortening cycle. As I like to coach it: Grip, dip, rip!

Digital Strategic Strength Workshop Coming Soon

For more insights on deadlifting, coaching, programming, assessment, and general badassery keep your eyes peeled for my upcoming continuing education resource which should be available this coming January!