This past weekend I attended the I Am Not Afraid To Lift Workshop at Iron Body Studios in West Roxbury, MA. It’s an event created by Artemis Scantalides geared mainly towards women – although men are encouraged to attend too – that teaches strength training as a form of empowerment, a road to improved confidence, and a less arduous avenue towards increased autonomy.

(In addition to giving the attendees any excuse to flex their biceps whenever possible).

It shouldn’t take more than 1.7 seconds to find where I’m located in this picture.

What made this past weekend particularly special for me was that my wife, Dr. Lisa Lewis (located front row, 3rd from left, next to Artemis, on her right), was a co-presenter invited to speak on the topic of mindset, dealing with negative self talk, and to elucidate further on some of the psychological hurdles that many trainees tend to encounter in the weight room…and in life.

As someone who works with a lot of women and who has long championed the idea that strength training is a good thing and something that should be embraced and not euthanized in lieu of buzz words like “toned,” “long,” “lean,” and “sexy”…I felt this was a perfect melding of worlds, and something there’s a massive need for.

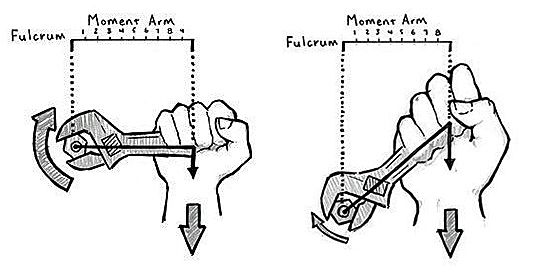

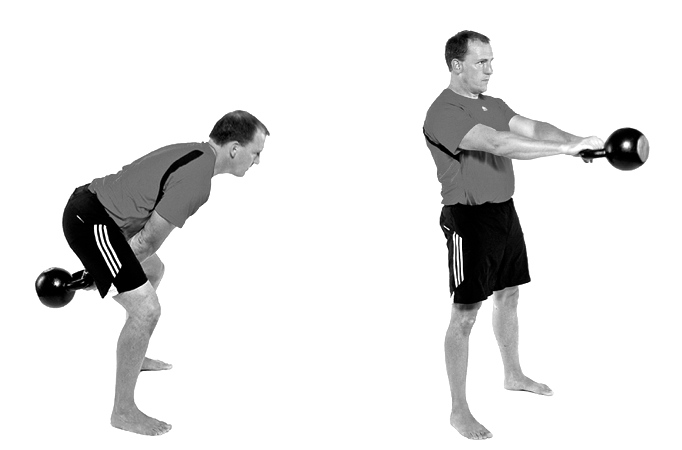

Artemis speaking to the intricacies of the deadlift, squat, swing, press, and chin-up/pull-up – both from a coaching/cueing and program design perspective – and Lisa speaking to many of the pervasive mental road blocks many women and men battle on a daily basis which CAN be managed with some easily implemented drills and strategies.

“Should-ing” On Ourselves

While speaking with an attendee about her anxieties and frustrations about not being able to hit a specific fitness goal, Lisa commented, “It sounds like your “SHOULD-ING” all over yourself, instead of feeling energized by your goal.”

The entire room erupted in laughter1. I’m lucky I wasn’t drinking anything at the time, because this totally would have been me:It was an awesome line, but not a Lisa original.

She borrowed it from Dr. Albert Ellis who’s the man responsible for something referred to as RET, or Rational Emotive Therapy. RET was popular decades ago, before CBT (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy) came on the scene. Ellis would focus on “irrational thoughts” as the source of our anxieties and negative emotions.

I have to assume there’s a book somewhere out there with big, fancy words or entire courses describing this type of therapy in more glamorous detail, but in other words it can be broken down like this:

The origin of your problem isn’t actually the problem… it’s how you’re thinking about the problem.

Some common health and fitness examples may include:

“I’m not fit until I can run a marathon or deadlift 2x bodyweight.”

“I’m not in shape until I have a six pack or I’m “x” dress size.”

“I have to workout every day.”

“If I don’t achieve my goal of hitting a bodyweight chin-up, I’m a failure.”

Lisa interviewing an attendee on her “mental roadblocks” and anxiety about hitting a specific fitness goal.

Many of us form these beliefs and inevitably turn them into doctrine:

Who says they’re real in the first place?

Who says you have to deadlift 2x bodyweight?

Who says you have to train everyday?

Who says you have to lose 10 lbs. in order to look good in a bikini?

Who said that? Who says these rules?

A trainer? An article your read on the internet? Some magazine cover? A Kardashian?

Even me?

Even if a reliable source makes a professional recommendation about what you “should” be doing – does that mean it’s come down from the mountain? No2. My goal as a fitness professional is to help – offer ideas, alternatives, new ways to approach your strength goals. But if something I (or anyone else) recommends doesn’t help, and in fact makes you stressed, feel bad, or NOT WANT to pursue your fitness goals, THROW IT OUT!

Try a different approach.

It’s All Made Up

The thing to point out – especially as it relates to YOUR goals and YOUR happiness – is that there are no rules. Everything – more or less – is someone else’s belief. Someone else’s opinion.

[Not coincidentally to help sell an ebook, or DVD, or Gluten-free, GMO, organic, Acai Pills soaked in Unicorn tears.]

That doesn’t mean it’s right for you.

As Lisa notes:

“Buying into a “rule” that makes you unhappy is the problem.”

And this is something that permeates into other aspects of our lives as well; not just fitness.

We make rules for ourselves – often irrationally and without much thought – and make a habit of measuring our happiness, sense of well-being, and worse, our overall sense of self-worth on our ability to successfully cross these rules off like a checklist:

- I have to – should – be married by the time of 28.

- I have to – should – make Dean’s List every semester.

- I have to – should– be making “x” amount of money per year.

- I have to – should – get caught up on Game of Thrones3.

Bringing the discussion back to health and fitness, according to Lisa:

“If “shoulding on yourself” is messing you up and makes you feel upset, then it’s time to reevaluate.”

That’s not the point of fitness. Don’t should on yourself.

If you can deadlift 290 lbs and your goal is 300, are you any less accomplished or less of a person? Does all the hard work you put in for the past few months (or years) all of a sudden become moot or negated because of 10 lbs?

It’s true: we celebrate growth and progress in the gym by how much weight is on the bar. We take before and after pictures. We set goals and standards for ourselves, which is fantastic.

However, once we allow someone else’s arbitrary (even if well intentioned) rule from a magazine or book affect our well-being – I should be avoiding carbohydrates after 6PM (even though I feel lethargic and want to drop kick everyone in the face), I should be back squatting (even though it never feels good, despite good coaching) – and it becomes more toxic than helpful… it’s time to change your mindset.

In the end who cares? What matters and what’s important is that you recognize the process is every bit as important as the outcome.

It’s time to stop SHOULDING all over yourself.

How about you? Any “shoulds” out there that you’d like to share? Lisa says it can help to acknowledge and “put it out there” to help yourself start to reevaluate what really matters…

Thanks for your thoughts!

I wrote back:

I wrote back: