The fitness/health community isn’t much different than every other community out there.

It’s just as “tribal” as the next.

There are factions who feel that heavy back squats cure everything (except herpes1) and that not including them in a program is sacrilegious and that it’s impossible to add muscle or get stronger without them.

And at the opposite end of the spectrum there are those who think if you even look at a barbell you’ll turn into He-Man.

The same dichotomy plays out in the nutrition realm as well. One week dietary fat is the enemy, and the next you’re the spawn of Satan if you offer someone a Diet Coke.

In both cases many are failing to recognize that the key to long-term progress, and progress that sticks, is the concept of focusing on PRINCIPLES.

- In order to lose weight you need to elicit a caloric deficit. There are myriad ways to to do so.

- In order to gain muscle you need to elicit progressive overload.

Squats.There are myriad ways to do so.

In today’s guest post via Michigan based trainer, Alex McBrairty (whom you may recall from THIS spectacular read), he elaborates more on this concept.

The Future of Fitness: Principle Based Coaching vs. Plan Based Coaching

The fitness industry is failing.

After a decade of working as a fitness professional, I see firsthand how many of the most popular products and programs leave people worse off—with the only benefits going to the people selling the products and services.

But I believe this is changing.

Slowly, a new approach to fitness is emerging. It’s one based in sound reason, eliminating the need for marketing gimmicks and fads. It’s called principle-based coaching.

Principle-based fitness coaching uses practices and strategies informed by first principles—ideas, concepts, and information that we know to be objectively true. The most base layer knowledge; Ideas and insights from psychology, human physiology, nutrition, and exercise science.

It’s the type of information that most traditional fitness plans cherry-pick to sell their particular spin on fitness.

- Paleo tries to limit processed foods.

- Keto tries to limit carbohydrate intake.

In reality, both of these diets work because they limit calorie intake.

The first principle being applied in both cases is calorie management. To lose weight you need to eat fewer calories than you’re expending. Both of those diets approach this problem in a different, hyper-focused way.

This more traditional style of coaching is called plan-based fitness coaching. Plan-based coaching, as the name suggests, uses specific plans to help users see the intended results. The main pitfall of plan-based coaching is the extra leap these plans take to reach their conclusions.

Plan-based coaching takes the objective facts of first principles and then makes additional assumptions about them to reach different conclusions.

If calorie management is the first principle, a Paleo plan jumps to the conclusion that processed foods are the reason you overeat.

A Keto plan jumps to the conclusion that carbohydrates are the reason you overeat.

Plan-based coaches make unverified claims to leap from first principles to their principles.

This results in fitness plans that are rigid, inflexible, and disconnected.

For someone following a Paleo or Keto (or other) plan, there is a rigid structure for selecting which foods are “good” or “bad.” This leads to a lot of black and white thinking.

“Good” Paleo foods are unprocessed, whole foods that our caveman ancestors consumed before agriculture. “Bad” Paleo foods are foods we didn’t begin to consume until we began to grow our own crops, including anything processed and produced in the modern era.

“Good” Keto foods are foods that are low in carbohydrates. High-fat foods like butter, bacon, cheese, or red meat are green-lit. “Bad” Keto foods are anything with carbohydrates. Don’t even think about consuming bread or pasta. Even fruit is considered bad in the Keto plan.

In each of these plans there is no room for nuance. There is good and there is bad. Pick a side.

It’s because of this rigidity that these plans are inflexible and less effective for most people.

The plan pays no attention to the accessibility of the good foods. Say you want to follow a Paleo plan but live in a food desert, where access to fresh, natural foods is scarce or nonexistent. In this reality, how can you stick to the tenets of such a rigid diet?

Just try harder.

At least, that’s the prevailing advice. And it isn’t much help.

Imagine that you attend a dinner party where you’re excited to see your friends. The food offered is a spread of vegetables, a bit of meat, some potatoes, and a fruit pie for dessert. If you’re following a Keto plan, instead of enjoying the company of your friends and eating sensibly, you spend your evening upset that the only thing you can eat is the meat.

The specific rules of the diet force you into inflexible eating patterns, causing even more stress and deterioration in your relationship with food.

Because these plans are rigid and inflexible, they remain disconnected from the real lives of the people they attempt to serve.

They may be helpful for some individuals, but that list is very short. Plan-based coaching might help give people more direction and a clearer focus on how to achieve their goals, but it is a far cry from addressing the complexity of human lives.

Even worse, what happens if the assumptions of the plan are wrong?

What if cutting out carbohydrates leads to additional stress and strain in navigating our carb-rich world? You find yourself giving up your favorite foods, avoiding social events, and worrying about your diet all day, every day. What if, after all of that, you come to find that carbohydrates were not the real problem the whole time?

Would it have all been for nothing?

This isn’t just a risk of eliminating carbohydrates. It’s the inherent risk of following a plan that is rigid, inflexible, and disconnected. It’s the risk of any plan based on unverified claims, a plan not based in first principles.

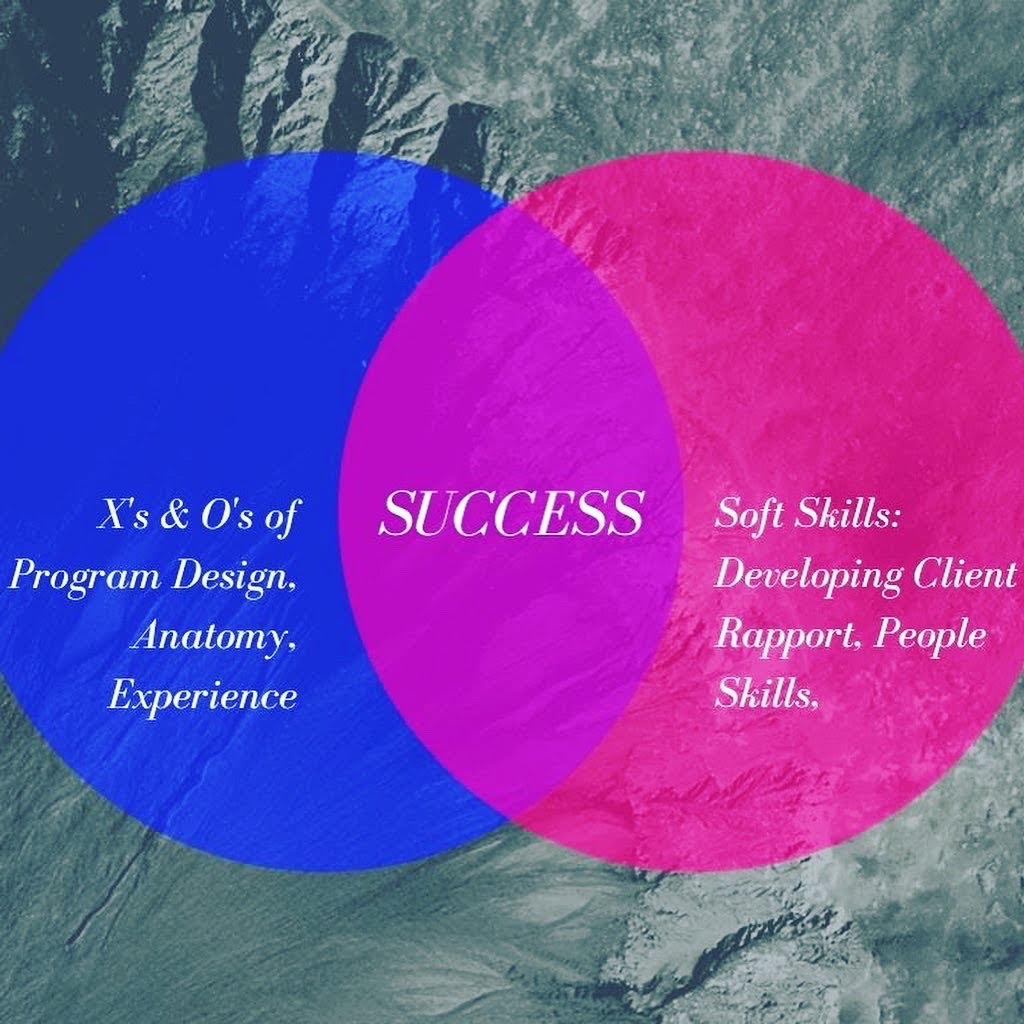

Principle-based coaching results in a program that is adaptive, flexible, and integrative.

Unlike plan-based coaching, which builds on additional, unverified assumptions about what is true, principle-based coaching begins with all the base-layer information that is objectively true:

Ideas like calorie balance, progressive overload, and self-efficacy.

The principles allow coaches to evaluate what must be true in order to see results, and then gauge how the program can be adapted to the needs of the unique individual in front of them.

If two individuals need to improve their calorie management, the principle-based program does not limit one from enjoying carbohydrates while the other decides they’d prefer to eat fewer carbohydrates. Both can coexist and see great results.

Principle-based coaching does not put every individual in the same bucket, nor make the same assumptions about each.

This ability to mold the program specifics to the individual makes these programs adaptive.

Because the means of achieving the first principles is non-specific, they are also inherently flexible to changing circumstances.

If you live in a food desert, where access to fresh, natural foods is scarce or nonexistent, you are empowered to make alternative choices based on what’s available. Not only are you empowered to make these changes, but you can do so and see the same (if not better) level of success as following a rigid plan.

If individuals find themselves at a dinner party, a social event, or traveling across the country, they will be able to adjust the specifics of their plan—the particular foods they choose or the types of movement they do—in order to satisfy the first principles.

The ability to adjust strategy, without negatively impacting results, makes these programs flexible to changing life circumstances.

Since principle-based coaching adapts the program to the unique individual and inherently allows for flexibility in how to achieve optimal outcomes, these programs integrate very well into the lives of those who follow them.

No matter the goal or phase of life, because these programs are rooted in objective truths, they can be molded to meet the needs of the individual as those needs change over time.

Another advantage of the adaptability and flexibility of these programs is that they allow for greater adherence and consistency—two important variables for successful outcomes. Greater levels of adherence and consistency lead to better results, both in the short- and long-term.

Principle-based coaching allows individuals to integrate good behaviors into the fabric of their lives, ensuring permanent success.

Fitness programming began as a way to educate people on how to live healthier lives. As time went on, we began to realize it wasn’t working. As the fitness industry grew, so too did the obesity rates.

The solution was to begin making assumptions about what people were doing wrong.

That led to the plan-based model previously described. That model is the most pervasive model for fitness programming that we currently have. The result?

Obesity rates continue to climb.

As of 2018, over two-thirds of the U.S. Adult population was overweight or obese.

Clearly something isn’t working.

And that’s because education is not the problem.

Sure, most people could benefit from a little more information about healthy lifestyle practices, but not in the traditional way of what’s good versus bad. If we’re going to educate people, educate them in first principles.

Because what we need is more action.

We need people to learn how to practice healthier habits consistently, not sporadically. We need to eliminate the prejudice around good and “good enough.” We need to empower people to make change, even if their life circumstances are less than ideal.

We need fitness programs that are adaptive, flexible, and integrative.

We need principle-based fitness coaching.

About the Author

Alex McBrairty is an online fitness coach who owns A-Team Fitness in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Obese as a child and teenager, he blends fitness and psychology to help his clients discover their own hidden potential.

He has a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Michigan and is certified by the National Academy of Sports Medicine.

His articles have appeared in Breaking Muscle and The Personal Trainer Development Center, and he’s contributed to Muscle & Fitness, USA Today, Men’s Fitness, and Prevention.

Website: ateamfit.com

Facebook: facebook.com/alex.mcbrairty

Instagram: @_ateamfit_