I’m still across the pond in London with Dean Somerset presenting our Complete Shoulder & Hip Blueprint workshop.1 I have zero plans to do work today, but a good friend (and colleague) of mine, George Kalantzis, was kind enough to pinch hit write for me.

He’s written several articles for this site and he’s a master at writing effective fat-loss programs.

Enjoy.

Training For Fat Loss Sucks!

In fact, the cards are stacked against you and mainstream media keeps flooding you everyday promising you with six pack abs shortcuts and seven day cleanses to only leave you frustrated and tired of results.

But Not Today

Over the past 15 years of my life, I have had the chance to train with some of America’s finest men as a Marine, and coach alongside some of the best in the fitness realm. I’ve learned some pretty cool training methods and have helped people lose anywhere from 5-40 pounds in a matter of a few months.

Because you are here to pick heavy things up and see results, you want a training method that will optimize time and accelerate fat loss.

And to be lean and athletic, you need to utilize combination exercises in your training to build more muscle and boost the metabolism so that your body continues to burn off calories well after exercise.

Combination Exercises and How The Accelerate Fat Loss

The common mindset or misconception seems to be that you can shred fat faster by doing two things- lower exercise at a longer steady duration or crush yourself into oblivion with high-intensity training.

While both play a vital role in fat loss and a well-rounded program, no one has time to train multiple hours throughout the week, ( if you do, I applaud you) and if you want to accelerate fat loss and keep burning calories well after your workout, you have to work hard and smart.

That means you have to find a training method that will burn a ton of calories, promote muscle mass, and elevate the metabolism.

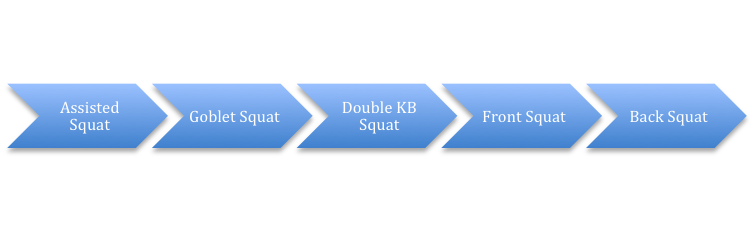

One of the best ways to accelerate fat loss is to utilize combination movements in your training program. Combination movements play a huge role in fat loss because they allow for the greatest muscle fiber recruitment and an increase in the resting metabolic rate.

By stimulating a greater amount of muscle fibers during a workout your body will see huge increases in metabolic demand, which in turn will increase EPOC (Exercise Post Oxygen Consumption). EPOC is the amount of oxygen consumed during recovery in excess than what would have been consumed at rest.

Essentially your body becomes a fat burning machine well after the workout.

Ok, so now that we’ve covered the why combination exercises work, let’s cover how to shred some serious fat!

How To Use Combination Exercises For Fat Loss

Just training hard and fast isn’t usually the answer to a good fat loss program. Or is running for hours on end on the treadmill and Stairmaster going to do the trick.

You need to stimulate the most muscle in the shortest amount of time while finding a sweet spot between failure and easy in order to boost your caloric deficit, a key component to getting shredded.

Combination exercises are great for fat loss because they use compound movement patterns with short rest periods and higher intensity. A must have for shredding that stubborn fat.

But before we get into the circuits, I want to walk about the method behind the madness of combination circuits.

I’m a huge fan of taking what has been known to work and finding out ways to make it better. Density training has been known as one of the best things you can to shred fat fast. The greater the density, the more fat you will burn. You can increase density by cutting rest times and set up circuits like the ones below.

Day # 1

1a) Upper/Lower Compound x12-15 Reps

1b) Push-up Progression 8-10 Reps

1C) Split Stance Progression/Core x6 reps

2) Quad Dominant x 5

2b) Vertical Pull x 5

2c) Core

Day # 2

1a) Upper/Lower Compound x12-15 Reps

1B) Inverted Row x 5

1C) Single Leg RDL Combo x 6/leg

2a) Hip Dominant x 15

2B) Horizontal Press x 5

2C) Core

These circuits are a bit more advanced, so use them as a starting point and make modifications where you can

Pre-Exhaust Method Combination – Then Heavy Equals Accelerated Fat Loss

Not all circuits are created equal. To stimulate the most muscle during a workout and keep burning fat well after the workout, you need to shock the system.

Traditional fat loss programs include lighter weight and higher reps to produce results. And while there is nothing wrong with those programs, I like my clients to maintain muscle while shredding fat.

This is where I like to combine pre-exhaust training with heavier training to accelerate fat loss. Pre-exhaustion is a way to fatigue the muscles before hitting them with compound multi-joint exercises. This method is old school but is a great way to wake up the muscles prior to the larger lifts and stimulate muscle growth. Which means you get to build some more muscle and keep shredding pounds.

Fair warning, just because the reps are higher and the load is lighter, does not mean it will be easy. You will soon begin to feel what pre-exhaustion meals into your second and third set.

Pre- Exhaustion Set For Fat Loss Looks Like This

A1) DB RDL/Bentover Row Combo x 12

A2) Tempo Pushup x 3-0-3 x 8

A3) Walking Lunge Into Renegade Row 6/side

Then You Would Rest No More Than 90 seconds and Get Right Into Heaver Weights

B1) Double Kettlebell Front Squat x 5

B2) Pull-up x 5

B3) Side Plank With Knee Drive 5/side

A second day would look like this

A1) Kettlebell Squat To Press x 12

A2) TRX Inverted Row x 10-12

A3) Single Leg RDL To Reverse Lunge Combo x 6/leg

B1) Kettlebell Swing x 5

B2) BB Bench Press x 5

B3) Push-up To Mountain Climber 5/side

Accelerated Fat Loss Summary

For most people, when it comes to shredding fat, being consistent with eating healthy and working hard produces results. Sometimes, you will need to think outside of the fat loss box and mix it up with different styles of training.

Harder, shorter training sessions work better than high reps and lower weights because they force you to recruit more muscles than a typical training session. Attack fat loss training with a specific goal and stick to it for at least 4-6 weeks. Use the training methods above at least two days a week and you will begin to see a transformation in your body composition.

Author’s Bio

George began his time at Cressey Sports Performance as an intern in the fall of 2013, and returned in 2014 as CSP’s Group Fitness Coordinator, overseeing all Strength Camp coaching and programming responsibilities.

George began his time at Cressey Sports Performance as an intern in the fall of 2013, and returned in 2014 as CSP’s Group Fitness Coordinator, overseeing all Strength Camp coaching and programming responsibilities.