I have a special cameo appearance today from one of the best collegiate strength and conditioning coaches on the planet, Coach Robert dos Remedios (or, ‘Coach Dos’).

Coach Dos is someone whom I respect a ton, and someone I feel has forgotten more than many of will ever know. 27 years “in the trenches” coaching, a lot, will do that.

He’s achieved the status of Master Strength & Conditioning Coach by the CSCCa (one of only 100 in the world), is a Nike Elite Performance Coach and was also the 2006 NSCA Strength Coach of the Year.

I once scored 18 points in a JV basketball game. No big deal.

He’s the creator of Complete Program Design, his latest resource which just became available, and was kind enough to take time to answer a few questions for me.

Enjoy.

Tony Gentilcore (TG):I live in Boston. We had THE worst winter in history last year. We had a 30 day stretch where we had 6-7 feet of snow fall. It made the national and world news. You live in California with 80 degree weather year round. Can you please explain to me why I continue to put myself

Coach Dos (CD): HAHA! Well as a Californian who puts on the beanie when it drops below 60 I completely understand where you are coming from. That being said, the beer and Pub game in Boston is second to none….that alone can get me scrape some ice off my car to grab a proper pint :o)

TG:Speaking of misery, as a reputable strength coach yourself, I know you don’t buy into the “I must destroy myself with every training session” mentality: can you give some insight – or at least an umbrella themed review – on your approach to program design?

Maybe some “big rock” methodologies or words of wisdom?

CD: I think I am pretty simplistic when it comes to program design….but it’s important to not associate ‘simple’ with ineffective. If you take an approach where you address all essential movement categories (explosive, push, pull, hinge, squat/step/lunge, and core (pillar and rotational) it’s hard to go wrong.

You won’t have any holes and you will avoid over/under training any movements.

As far as crushing folks every session, it’s a common theme we see these days but the first indicator that the coach/trainer doesn’t have experience in the real-world.

I need my athletes to be able to perform and I can’t afford for them to not be ready to DO WORK in their next session with me. If folks are paying you to train them and you continually crush them each session, you will most likely not be a very successful private sector coach/trainer.

TG:No diggidy, no doubt. What are some of your biggest pet peeves with regards to program design that some fitness professionals make?

CD: The ‘whiteboard workouts’ – these are the workouts that are generally created on the spot and have little rhyme or reason to the intensity, volume or actual exercises. It’s that random-randomness of these workouts that make them ineffective for most long term goals. Sure it can result in lots of sweat and anguish, but what role does this session play in your big picture?

The other kind of workout that bugs me? The fictional kind.

These are the ones that lots of internet gurus come up with on their computers and have never actually been tested on humans. They are generally characterized by unrealistic volumes, rest periods, or simple things like tri-setting deadlifts, DB walking lunges and chinups (Hint: aint gonna work haha!).

TG:Wait, what? Why?….;o)

With regards to assessment, what are some of the big hitting things you look at with your athletes and clients? Can you give insight on what “markers” you look for and want to improve on with your programs?

CD: We may use the FMS or we may just take athletes through simple movement prep drills and actual exercises to expose some red flags. We obviously want them all to move well and some do immediately while others are a work in progress.

Over the past 5-6 years we have really made mobility a priority with everyone (which is why we incorporate mobility drills within all of our lifting sessions) and we have seen great benefits. Some of the things we strive for are great squatters, hingers, and athletes with great unilateral strength and stability.

TG:Overtraining? Discuss.

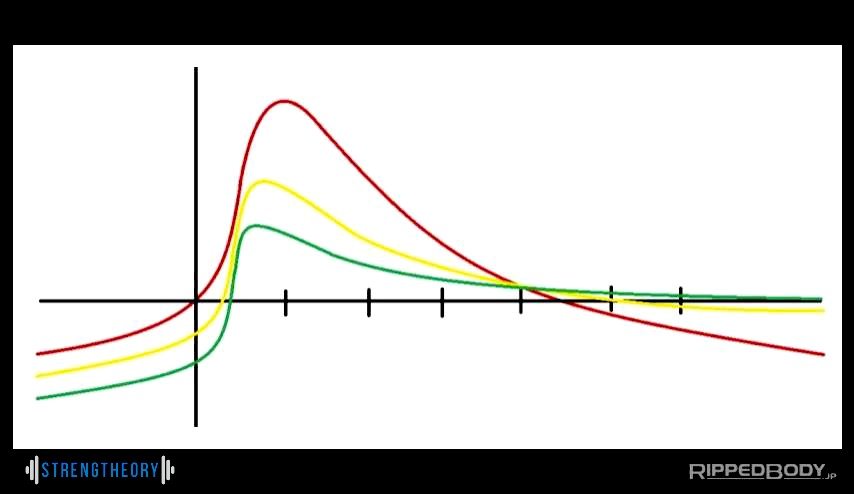

CD: I’m a big ‘work capacity’ guy, it has always been the bedrock of my training philosophy.

Because of this we try to push the envelope when we train. I feel like the system we have used allows us to get after it hard, recover, and bounce back to attack the next training session. Our history of building better athletes and resisting injury has been pretty outstanding over the past 17 years at the college.

So in a nutshell can you overtrain? Sure, but if you have proper systems in place and keep the big picture in mind you can easily avoid it.

TG:For general fitness clients with little or no experience with the OLY lifts: what are some of your “go to” drills to help kick-start the process?

CD: The Olympic lifts (and all their variations) are favorites of mine but I am in it for one reason – Quadruple extension (yes I said quadruple, not triple haha!).

Think ankles, knees, hips, and low back powerfully extending. This can be easily accomplished via jumps, Med ball Scoops etc. band resisted jumps of all kinds are big go-to exercises for all populations as they add load and really force this ‘quadruple extension’.

TG:In terms of conditioning, any pet peeves or insights you can offer? How much is too much?

CD: I think people having a lack of understanding of energy systems especially when it comes to specific sport-demands.

I hate it when I see coaches make twitchy-explosive athletes do long, slow, aerobic activity. I call it ‘making joggers out of jumpers’.

If you truly believe that even your explosive athletes with virtually no aerobic demands in their sport need some sort of aerobic work at least accomplish this via fartleks or other aerobic-interval work. Makes me cringe seeing power athletes plodding along a cross country trail or track.

TG:Thanks so much for your time Coach! All useful information and just the tip of the iceberg in terms of your knowledge and how you go about making your athletes (and general fitness clients) savages.

I’m a movie geek, and I like to expose to people that not all us coaches are Terminators (<– See, what I just did there?) and that we have life outside of strength and conditioning. So I have to ask: top 5 favorite films of all-time?

CD: Tough Question so I’ll give you an eclectic mix….Happy Gilmore, Super Troopers, Old School, Vanilla Sky, and Silence of the Lambs.

This should give a little insight into my psyche haha!

Complete Program Design

Is a culmination of 27 years of coaching. 27 years of trial and error, successes, modifications, additions and most important of all…results.

You get a 100+ page manual breaking things down into several 2-3 and 4x per week programs. You also get an extensive exercise database of 130+ exercises and movements. Coach Dos coaches YOU.

It’s impressive to say the least, and something I know will help me step up my own coaching game. It’s an excellent resource for any coach – newbie or experienced – and it’s on SALE this week at a hefty discount.

For more information go HERE.

.

.