Today’s guest post comes from physical therapist and strength coach Dr. Michael Stare. Mike is wicked smart, wicked fit, and wicked good looking. I hate him because I’m not him….;o)

I’ve known Mike since I moved here to the Boston area in 2006 and have corresponded with him intermittently in that same time frame.

I’m not going to lie: This post may rub some people the wrong way, as Mike delves into the whole bracing vs. drawing in debate as well as burns some sacred cows with regards to the efficacy behind MRIs.

HINT: they’re not as “helpful” as you would think.

Nonetheless, I think you’ll all enjoy this one for sure.

I love sharing and gathering information about health and fitness, so when a recent exchange with Tony lead to him suggesting I guest post about lumbar spine issues, I was thrilled to jump at the chance. And when given the license to get all nerdy and drop some geeky science because he says his readers are super smart (no surprise given who Tony is), well how the hell could I not get excited?

I’ve been very fortunate to obtain some great perspectives into treating and managing lumbar spine pathology from formal education, clinical experience, and personal experience as a patient. From that vantage point, I wanted to share some insights addressing some of the most controversial issues regarding spine health, and provide some suggestions about prevention and treatment. This should be should be very important information to you because:

1. As fitness fanatics you want to push the envelope of human performance, which often means walking a fine line between adaptation and injury,

2. 80% of the population will experience low back pain in their life, and 90% of first time episodes will reoccur. Translation: in all likelihood – you will experience a back injury so you best learn how to reduce your chances and manage it properly when it happens. And finally,

3. based on the above, in all likelihood someone you know and care about, or even advise, is dealing with back pain.

I’m not going to bore you with the oft regurgitated platitudes like “we need to stabilize more” or “this exercise is the root of all evil and will make your spine disintegrate” nor will I tell you that sitting up straight will cure every condition. Instead, I want to get at some hot button topics and provide some practical solutions rooted in evidence and real world results. Part 1 will deal with the debate on drawing in vs bracing and the usefulness of imaging for determining the cause and treatment of low back pain.

The bracing vs drawing in debate

Ever since the smarty pants Aussies in the late 90’s (Hodges, Richardson Spine 1996) released some great studies about motor control dysfunctions being common in those with spinal disorders, it seems like there has been more confusion about how we should train the torso to affect back issues. I think it’s like that game “telephone” you played when you were a kid. Each time the message gets passed on, it gets distorted so that by the end of the line, it rarely resembles what the original message was.

So let’s get to the original message:

These researchers had a hunch that motor control errors were occurring in those with low back pain. In particular, they believed those with LBP would not recruit their stabilizers properly in anticipation of a routine destabilizing event, like moving the limbs. So they tested this on subjects with and without low back pain. Subjects alternately lifted an arm and testers recorded patterns of truck muscle activation.

There was a subtle, yet consistent difference between those with LBP and those without. In the LBP folks, there was a delay in recruiting one muscle group by a milliseconds compared to those without LBP. This muscle group was the now famous transverse abdominus.

The conclusion: there appears to be a subtle delay in recruitment of the transverse abdominus in a subset of those with LBP versus those without LBP. Yet, as the message penetrated the ranks of PTs’ Chiros, Trainers, butts and cuts class leaders, yoga instructors and pilates folks, the message sounded a little more like this:

“The Transversus abdominus is the most important stabilizer, the transversus must be selectively activated to stabilize and improve motor control, and the best way to recruit the transversus and thus stabilize the spine is to perform a hallowing out maneuver.”

Sound familiar? Well, this isn’t really what the original research concluded. And research since hasn’t supported that the above is actually true.

For example, it has been determined that the drawing in or hallowing maneuver actually reduces spinal stability. This makes a lot of sense. Imagine the abdominal muscles are like a bunch of friends lifting a couch. Then you ask 3 of them to take a rest, leaving just one to do most of the work. As a result, you’d probably have a hurt friend or broken couch. Clearly, it’s best to have all the muscles recruited to stabilize in anticipation of movement or loading, which is what a bracing maneuver facilitates.

Remember, the research did not say that those with LBP are not recruiting the TA. Instead, it was just recruited slightly later – in a small subgroup of those with low back pain. Many studies since have shown that delayed activation of other key muscles, like the spinal erectors, the QL, and the latissimus have also been found in subjects with back pain. Training to brace in anticipation of instability in various positions would satisfy the anticipatory recruitment while also ensuring all muscles were involved.

So the preoccupation with the drawing in maneuver or transverse abdominus is not supported by the research and is missing the point in finding a solution for low back pain. Both Mc Gill and Hodges agree that the days of looking for one dysfunctional muscle for the low back solution is ill advised.

I think the best insights gleaned from this are that:

- LBP may be caused by, or the result of (chicken or the egg thing) anticipatory motor control impairments. This means the brain must learn to recruit stabilizers before movement.

- All stabilizers are important, and it might not be practical or possible to selectively activate or train them separately anyways.

Lumbopelvic Proprioception – lost in the shuffle?

I believe it is at least as important, if not more important, that people focus on lumbopelvic proprioception versus muscle activation.

I believe it is at least as important, if not more important, that people focus on lumbopelvic proprioception versus muscle activation.

To illustrate this, think about this scenario: You are about to throw a punch with your wrist cocked. How well would that workout for you when you make impact? Clearly, not well, and you’d probably end up with a broken wrist. Now, imagine doing the same thing, except your forearm muscles are jacked and maximally recruited, with your wrist still bent. What’s the result? Yup – the same thing – a badly damaged wrist. So the point here is that muscle activation is critical, but not unless your joint is positioned such that it can optimally distribute forces imposed upon it.

The Very Limited Role of Imaging in treating Low Back Pain

For all the wonderful things technology and imaging has done for our healthcare system, I think MRI is responsible for our health care system taking a major step backwards in dealing with the low back pain epidemic, not to mention the hefty financial burden.

The facts are that MRI is very poor tool to help determine the cause, the source, and the best treatment for back pain. These facts are well established in the literature.

For example, one study revealed that 90% of people without back pain were found to have disc herniations on MRI (Boden SD, et al J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:403-408). Another study looked at a large population also without low back pain, and took baseline imaging (Carragee E. et al Spine J. 2006;6:624-635. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2006.03.005).

They were followed for 5 years and inevitably, a percentage of those people went on to develop LBP. These people were then reimaged, and their findings while suffering from LBP were compared to their baseline findings before they had pain. The conclusion? In 84% of them, their “in pain” images were either unchanged or actually better than their pain-free baseline images!

Clearly, the correlation between pain and imaging is poor. What the research suggests is that these pathologies may be painless aberrancies and conversely that pain can be present in spite of the absence of significant structural damage, as suggested by Deyo et al (NEJM, 2001) who found no pathology in 85% of people with LBP symptoms.

OK, so now we are clear that MRI doesn’t tell us the source of pain or exactly how to treat low back pain. So when should MRI be used? Whether you are gym rat or clinician, this is important to know:

1. If there are red flag signs suggestive of systemic pathology (like tumors, cancer, etc) like fever, vomiting, night pain, unexplained weight loss, etc or a past history of cancer. All clinicians are well trained to recognize these signs.

2. If there is saddle anesthesia (suggestive of cauda equina) or progressive neuro compromise (continued loss of motor, sensory, or reflexes). Again, these are easily discernible by clinical exam (however, I must say I am shocked by the number of PTs, PCPs, and surgeons who don’t know how to do a proper neuro exam. I can tell you, that if you know anyone who went through the IOMT residency or fellowship in nearby Woburn you can guarantee they do a proper neuro exam)

Otherwise, MRI or other imaging won’t be helpful.

In fact it might actually cause harm for a few reasons.

For example, increased radiation exposure, exposure to contrast materials (CT), and increased risk of surgery are significant concerns. A less appreciated risk is what happens when people are labeled with a pathology (again, one that as discussed above may actually have little to do with their pain and dysfunction). Many people respond to that with a logical question: “But won’t it just make people feel better knowing they got it completely checked out, and extensive pathology was ruled out?”

Based on the research, no it won’t. First, it doesn’t do a better job of doing these things as using the above criteria is enough, and second studies reveal that it did not improve patient satisfaction or ease anxiety (Chou R,et al. Lancet. 2009;373:463-472.). Evidence indicates that those who are labeled with pathologies from imaging may actually have worse outcomes (Fisher ES, JAMA. 1999;281:446-453).

I see this all of the time. People will be in a holding pattern, waiting to address the obvious causes of their back issues until the smoking gun can be revealed by the MRI. We all have a need to be validated, believing such suffering can only be explained by the most elaborate technology, and anything less trivializes the severity of our condition. People sometimes feel offended when simple explanations are offered to explain their problem, even if addressing these issues leads to less pain! What people really want is someone to listen, then patiently and persistently seek the cause and explain the solution. In absence of this, they will stray, looking towards some elaborate technical gizmo which ultimately disappoints.

I wish everyone could see the face of my patients when they come in with their radiology reports. They read the scary terms with fear and uncertainty, giving rise to the paralysis by analysis syndrome at best, and at worst, fear avoidance behaviors. I am often the first to explain to them terms like “degenerative disc disease”, “decreased disc height”, “facet arthropathy”, or “mild to moderate bulging of L5” as common findings found on the majority of MRIs of people without any symptoms. Unfortunately, this might be after all the negative effects of paralysis by analysis have already set it, so I’ll have my work cut out for me.

Hopefully the take away here is that we cannot use machines to reduce our responsibility for problem solving. This requires us to ask focused questions to match patient tendencies with the natural history of LBP based on the available evidence, and observe and correct impairments associated with many types of back pain – possibly in addition to the imaging findings. We can all play a role in this by empowering patients to be a part of the problem solving process and fixing their back.

Stay tuned to Part 2, dealing with the issue of whether spinal flexion and rotation in training is bad, as well as suggestions to prevent and treat spine issues.

Author’s Bio

Dr. Stare is the Director and Co-owner of Spectrum Fitness Consulting, LLC, in Beverly, MA, where he trains clients of various fitness levels seeking weight loss, improved health, and performance enhancement. Mike received his BS in Kinesiology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, his MS in Physical Therapy from Boston University, and his Doctorate of Physical Therapy from the Massachusetts General Hospital IHP. Mike is a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapists and also practices with Orthopaedics Plus in Beverly, MA as a Physical Therapist.

Dr. Stare is the Director and Co-owner of Spectrum Fitness Consulting, LLC, in Beverly, MA, where he trains clients of various fitness levels seeking weight loss, improved health, and performance enhancement. Mike received his BS in Kinesiology from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, his MS in Physical Therapy from Boston University, and his Doctorate of Physical Therapy from the Massachusetts General Hospital IHP. Mike is a Fellow of the American Academy of Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapists and also practices with Orthopaedics Plus in Beverly, MA as a Physical Therapist.

In addition to his clinical practice, Dr. Stare lectures nationally to fellow clinicians regarding the proper treatment and prevention of lumbar spine disorders and fitness. He also provides seminars locally on weight loss, performance enhancement, and rehabilitation for young athletes to seniors. Dr. Stare has obtained the Certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist (CSCS) distinction, which is regarded as the gold standard certification in the fitness industry. Mike is also a Board Certified Nutritionist by the American College of Nutrition, and has been training clients for over 15 years. Mike resides in Windham, NH with his wife and three girls. To learn more about Spectrum Fitness Consulting, go to www.spectrumfit.net.

posterior chain strength preventing injuries.

posterior chain strength preventing injuries.

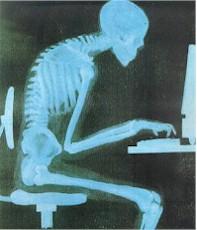

properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.

properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.

position as they roll around (reference the fine looking gentleman to the right).

position as they roll around (reference the fine looking gentleman to the right).