Today’s guest post comes courtesy of TG.com fan-favorite, Justin Kompf. And by “fan-favorite” I mean his one fan, his mom.

Just kidding.

Justin’s my good friend, occasional training partner, and has written a ton of content for this site, but it’s been awhile…

…and I was excited to see this article waiting in my inbox this morning. The title of the email was “really, really good blog,” and, begrudgingly (because Justin is the opposite of modest when it comes to E.V.E.R.Y.T.H.I.N.G), I have to admit, he was right.

It’s superb.

Trashing the Word Can’t: It’s Either You Will or You Won’t

Only twice in my life have I deadlifted 600 pounds.

I cannot do that now. There remains a plethora of other feats that I cannot do. I cannot run a five-minute mile. I cannot bench double my body weight and I cannot jump four feet in the air.

However, I certainly can deadlift, I can run, I can bench press, and I can jump.

Saying you cannot do a behavior is like saying you cannot ask out a person you like. You can, but for any number of reasons, you’re just not going to.

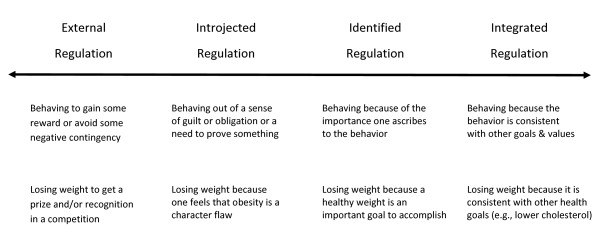

In fitness, there are outcome goals and there are process goals. Process goals lead to outcome goals. Deadlifting, the process goal, leads to the 600-pound deadlift, the outcome goal. Reducing calories, the process goal, leads to a lower body fat percentage, the outcome goal. Processes cause outcomes.

Outcome goals are not plausible in the here and now.

You cannot achieve them now because they are in the future, and often far away. Process goals are here and now, and they are plausible.

You can do them today.

For process goals, cannot is often a misused word.

It sets up a false narrative that allows for stagnation. Yes, with 100% confidence you can go to the gym and lift. Yes, with 100% confidence you can eat vegetables. Once cannot and can are used properly and the right words are used instead (“I don’t want to”, “I don’t feel like it”) you can actually move forward to different options or maintain the status quo.

Your choice.

A Clear-Cut Definition of Can and Cannot

Any student who has spent a semester in an introductory psychology class has inevitably heard of the importance of self-efficacy, a person’s confidence in their abilities to execute a task. Confidence in abilities plays a pivotal role in whether a behavior is initiated. For example, even if I wanted to Salsa dance tonight, I couldn’t because I don’t have the skills to do so.

I could dance or move my body in a way that someone may be able to make an educated guess that I am dancing. But it’s not Salsa.

In a 2016 paper, Ryan Rhodes, a researcher out of the University of Victoria, dived into how can and cannot are misinterpreted. Participants were asked to rate their confidence that they could do resistance training two times per week for at least 20 minutes on a graded percent scale where 0% meant cannot do at all and 100% meant definitely can do.

After they recorded their answers can and cannot were properly explained.

Cannot was described in a similar way to my 600-pound deadlift or 5-minute mile example. No matter how hard I try, I would have no confidence that I can run a 5-minute mile. Can was explained similarly to the asking a crush out example.

The capabilities are there, you just aren’t going to do it.

Once can and cannot were properly explained, confidence values for resistance training increased. Nothing really changed though, other than the understanding of the word can. They realized they could do it; that is, they have the capabilities.

Prior to the explanation capabilities were considered the same as motivation. Stated otherwise, they had the capability; they just weren’t motivated.

There we have it, can and cannot.

If you have done resistance training or exercised within the last year even once, you certainly can do it. If you have had a single bite of broccoli you can eat vegetables. While the skill set may not be there to do a back squat or make a ratatouille casserole you certainly can do a leg press and put baby carrots into your mouth. It just might be hard, but entirely doable.

Moving on, it’s best to trash the words “can’t” and “cannot.”

What Can I Do That I Am Willing to Do?

As a disclaimer, there are real “cannots.”

You cannot do a back squat unless you have a gym membership or a squat rack. Nor can you go for a run without running shoes.

Limitations are real but only exclude a small percent of us from exercise and improvement.

“What can I do?” is going to be the first question, immediately followed by “what am I willing to do?”

Goals necessitate a willingness for change. An opportunity-cost will always exist in a change effort. What am I willing to give up to get what I want? Drinking 30 beers a week is counterproductive to a weight loss goal. If you are lifting weights for 90 minutes you cannot simultaneously be watching Netflix on your couch for 90 minutes.

Opportunities have a cost.

If you’re not willing to give on anything, be honest with yourself, it’s a motivation issue not a capability issue. If you’re willing to give on something, then it’s time to design your change menu.

Design Your Change Menu

Your change menu is composed of what you can do AND what you are willing to do. If you don’t know how to do certain exercises it can’t be on your menu.

Your menu would need to say “learn how to do X,Y,X” instead.

If you don’t know how to write your own fitness program you cannot say “write my own fitness program.” It needs to be “hire someone to write my program” or “hire someone to teach me to write a program.”

If you can do it, what are you willing to do? How much time are you willing to dedicate to it? Are you willing to go faster? To lift heavier?

If you can run, what are you willing to do? How far, how fast, how many days?

If you can lift, what are you willing to do? What exercises, how long, how many days?

We often have lofty fitness goals, abstract visions of six pack futures, jaw dropping physiques.

For the most part we are entirely capable of doing the things that would lead us to get there.

- We can cut calories.

- We can push ourselves to lift heavier, to accumulate greater training volume, to learn new exercises.

- We can persist year in and year out.

Match your goals to what you are willing to put on your change menu.

I realize it’s just vernacular, but it’s words that tell us the story we follow. It’s rarely an issue of if you can do it. Arguably, most reasonable fitness goals can be chipped away at with time and persistence. It’s all a matter of picking what you can do right now and choosing goals that match what you are willing to do.

About the Author

Justin Kompf is doctoral student studying exercise and health sciences. He is a personal trainer in Boston at CLIENTEL3.

You can follow Justin here and here.

(He’s obsessed with his girlfriend’s dog).

Michael is a USMC veteran, strength coach, amateur surfer, and semi-professional mushroom connoisseur. As an intelligence officer and MCMAP instructor Michael spent the majority of his military career in the Pacific theater of operations.

Michael is a USMC veteran, strength coach, amateur surfer, and semi-professional mushroom connoisseur. As an intelligence officer and MCMAP instructor Michael spent the majority of his military career in the Pacific theater of operations.

Dr. Lisa Lewis is a licensed psychologist with a passion for wellness and fitness. She earned her doctorate in counseling psychology with a specialization in sport psychology at Boston University, and her doctoral research focused on exercise motivation. She uses a strength-based, solution-focused approach and most enjoys working with athletes and athletically-minded clients who are working toward a specific goal or achievement.

Dr. Lisa Lewis is a licensed psychologist with a passion for wellness and fitness. She earned her doctorate in counseling psychology with a specialization in sport psychology at Boston University, and her doctoral research focused on exercise motivation. She uses a strength-based, solution-focused approach and most enjoys working with athletes and athletically-minded clients who are working toward a specific goal or achievement.