I remember when Julian was first born my wife and I had many, many “checklists” to make sure that our schedules were in line so that we knew who was doing what, and when to make sure that 1) Julian would be fed and 2) he’d get his naps in. We weren’t playing games with that shit.

It’s funny, though. It’s been a trip to see how I make connections and correlations between that and stuff I see and come across in my professional life… training and coaching athletes/clients.

One of the purest examples is something I witness on an almost weekly basis.

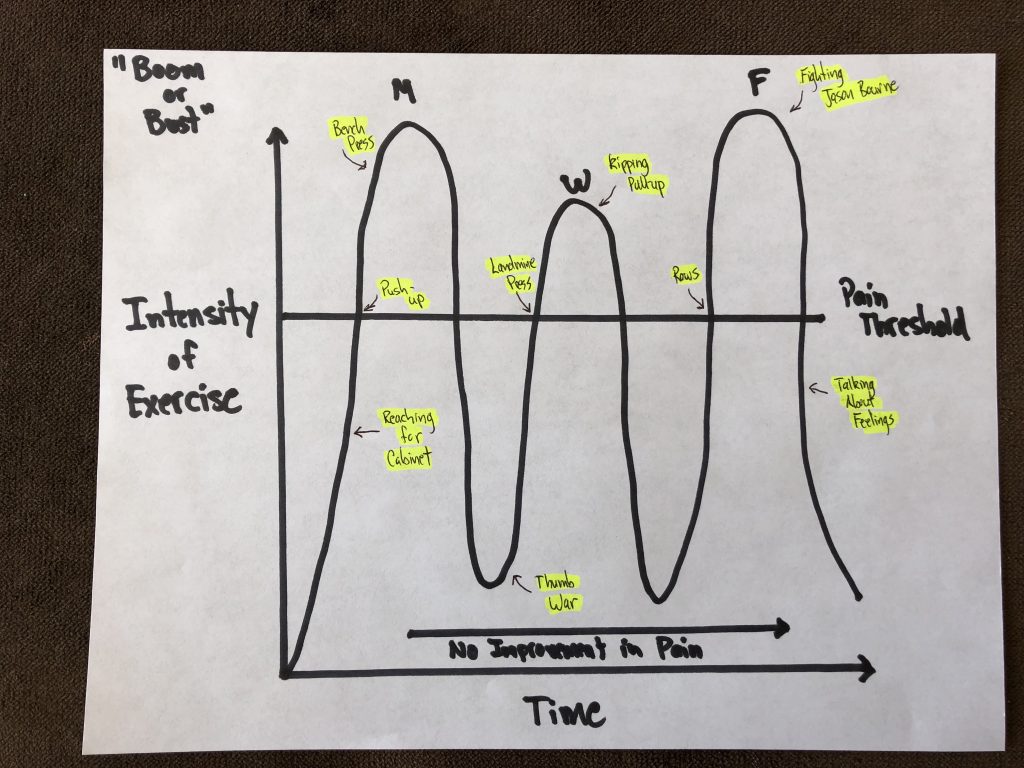

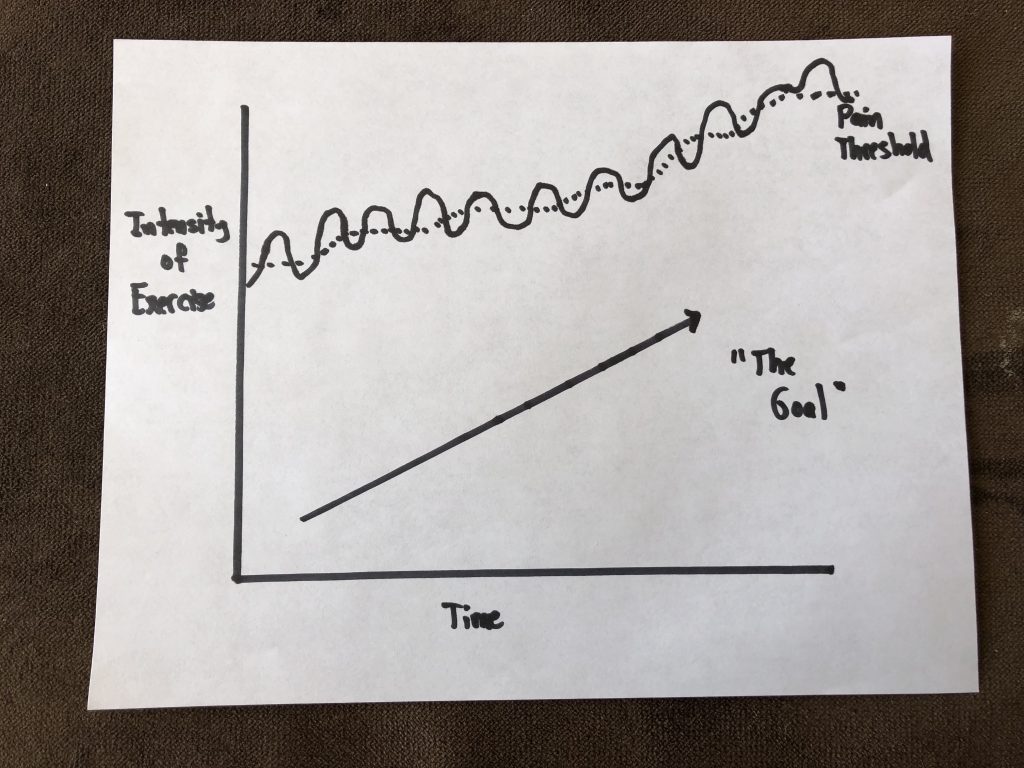

Many of the new people who start with me are beginner or intermediate level meatheads (male and female) who, for whatever reason(s), have been dealing with a pissed off shoulder that inhibits their ability to train at the level or intensity they’d like. It’s frustrating on their end and it’s my job as the coach to try to peel back the onion and see what may or may not be the root cause or causes.

That being said, I try not to go too deep down the rabbit hole. There’s a fine line between doing your due diligence as their coach and figuring out what may be causing their shoulder ouchies and making them feel like a patient.

READ: No one, and I mean NO ONE likes go to their personal training session and do rehab exercises for an hour. I’d surmise most would rather jump into a pool of lava. To that end, here’s my quick “go to checklist” whenever I have a client express that their shoulder hates them at the moment.

The “My Shoulder Hurts” Checklist

1) Technique

Most commonly people will note how bench pressing bothers their shoulder(s). Working on their technique is the baby check list equivalent of blow out explosive diarrhea.

I.e., It’s code mother-fucking red.

Following the mantra “if it causes pain, stop doing it” is never a bad call, and I am all for nixing any exercise or drill that does such a thing. However, I don’t like to jump to conclusions too too quickly. Sometimes making a few minor adjustments to someone’s technique or setup can make all the difference in the world.

Almost always I’ll have to spend some time on their set-up. I like to cue people to start in a bridge position to drive their upper traps into the bench and to set their scapulae (together AND down).

We can make arguments as to what this is actually doing. Some will gravitate towards it improving joint centration. Cool (and not wrong). I like to keep a little simpler and note that all it really does is improve stability.

Stability = strength

Another thing to note is many people tend to flare their elbows out too much when they bench which leaves the shoulders out to dry and in a vulnerable position.

MINOR NOTE: Since recording that video above (many years ago), I have since changed my views slightly thanks to some cueing from Cressey Sports Performance coach Tony Bonvechio. Elbows tucked on the way down is still something I’m after (albeit some are too aggressive at the expense of placing too much valgus stress on the elbows). However, when initiating the press motion, in concert with leg drive, allowing the elbows to flare out a teeny tiny bit (in an effort to keep the joints stacked and to place the triceps in a more mechanical advantage) will often play huge dividends in performance.

In the end, much of the time it comes down to people not paying any attention to how crucial their set-up is. It’s amazing how often shoulder pain dissipates or disappears altogether with just a few minor adjustments.

2) What People Don’t Want to Hear: Stop Benching, Bro

This is where the Apocalypse begins. Telling a guy (usually not women, they could care less) that he should probably stop benching for the foreseeable future is analogous to telling a CrossFittter they can’t tell you they CrossFit.

The thing about holding a barbell is that it “locks” the glenohumeral joint into internal rotation which can be problematic for a lot of people and often feeds into impingement syndrome.

[The rotator cuff muscles become “impinged” due to a narrowing of the acromion space.]

NOTE: I hate the term “shoulder impingement” because it doesn’t really tell you anything. There are any number of reasons why someone may be impinged. Not to mention there are vast differences between External Impingement and Internal Impingement….which you can read about in more detail HERE.

If bench pressing hurts, and we’ve tried to address technique, I’ll often tell them to OMIT barbell pressing in lieu of using dumbbells instead. With DBs we can utilize a neutral grip, externally rotate the shoulders a bit more, and open up the acromion space.

Or, maybe they can still barbell press, albeit at a decline. When you place the torso at a decline the arms can’t go into as much shoulder flexion and you’re then able to avoid the “danger zone.”

If all else fails, sadly, you may have to be the bearer of bad news and tell someone that (s)he needs to stop benching for a few weeks to allow things to settle down.

3) Let the Scaps Move, Yo

Above I mentioned the importance to bringing the shoulder blades together and down in an effort to improve stability.

If you want to lift heavy shit, you need to learn to appreciate the importance of getting and maintaining tension. That said, if lifting heavy shit hurts your shit, we may need to take the opposite approach. Meaning: maybe we just need to get your shoulder blades moving.

When the scaps are “glued” together and unable to go through their normal ROM it can have ramifications with shoulder health. Push-ups are a wonderful anecdote here.

Unlike the bench press – an open-chain exercise – the push-up is a closed-chain exercise (hands don’t move) which lends itself to several advantages – namely scapular movement.

4) More Rows

This one will be short and sweet. Perform more rows. Many trainees tend to be very anterior dominant and spend an inordinate amount of time training their “mirror muscles” at the expense of ignoring their backside. This can lead to muscular imbalances and postural issues.

This makes me sad. And, when it happens, a kitten becomes homeless.

You sick bastard.

The easy fix is to follow this simple rule: For every pressing motion you put into your program, perform 2-3 ROWING movements. Any row, I don’t care.1

5) Address Scapular Positioning

I’m going to toss out an arbitrary number and I have no research to back this up, but 99% of the time when someone comes in complaining of rotator cuff or shoulder issues the culprit is usually faulty scapular mechanics. Sometimes people DO need a little more TLC and we may need to go down the “corrective exercise” rabbit hole.

The scapulae perform many tasks:

- Upwardly and downwardly rotate

- Externally and internally rotate

- Anteriorly and posteriorly tilt.

- AB and ADDuct (retract and protract).

- Will clean and fold your laundry too!

They do a lot. And for a plethora of reasons, if they’re not moving optimally it can cause a shoulder ouchie. Sometimes people are too “shruggy” (upper trap dominant) with overhead movements, or maybe they’re stuck in downward rotation? Maybe they can’t protract enough and need more serratus work? Maybe they lack eccentric control and need a heavy dose of low trap correctives?

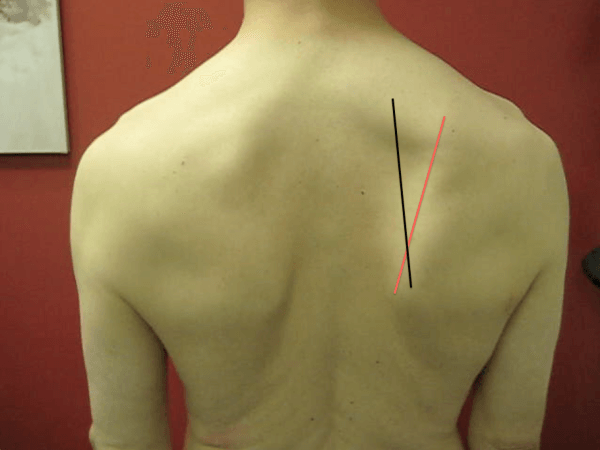

It dumbfounds me the number of times I have had people come in to see me explaining how they had been to this person and that person and NO ONE took the time to look at how their shoulder blades move.

I don’t like to get too corrective too soon, but if I’ve exhausted all of the above and stuff still hurts….it’s time to dig deeper.

If only there were a resource that dives into this topic in a more thorough fashion.

Hmmmm…………..Sha-ZAM.

Dr. Michael Infantino is a physical therapist. He works with active military members in the DMV region. You can find more articles by Michael at

Dr. Michael Infantino is a physical therapist. He works with active military members in the DMV region. You can find more articles by Michael at