Today’s guest post comes courtesy of Jennifer Vogelgesang Blake – or JVB as she’s affectionately called – a coach at The Movement Minneapolis, competitive powerlifter, and author (along with Jen Sinkler) of Unapologetically Powerful, a new resource designed as a go-to source for learning the “big 3” lifts, and removes the intimidation often attached at their hip.

Or weight clamps in this case.

Anyone can (and will) benefit from this resource – especially beginner and intermediate lifters who are even the slightest bit interested in competing and/or honing their technique.

And, I’d be remiss not to mention I feel this is a home run for any woman who may be on the fence about this whole “lifting heavy things” thing.

Without further ado, I’ll let JVB take it from here. Enjoy!

3 Squat Variations You Haven’t Tried Yet, But Need To

I’m going to be bracingly honest with you. If I were forced to choose, with my feet to the fire, I would have to own up to liking to squat more than I like to deadlift.

(I can picture Tony Gentilcore’s eyes firing up like Darth Sidius in The Empire Strikes Back and pledging an oath to never host a guest blog from me on his site ever again. This is what they call “going out on a limb.”)

I don’t think it’s unusual for lifters to hold a slight allegiance to one or the other. Both big lifts remind me of a bricklayer laying bricks: strengthening the quads, hams, back, and core are going to construct a house no one is going to be able to knock down. Even so, to me, there’s something really thrilling about loading a bar onto your back and refusing to let it plaster your face into the ground.

Squats open up the lifting in a powerlifting meet.

Of the three main lifts (back squat, bench press, and deadlift), squats come first. I’ve come to regard this lift as the party starter—it sets the tone for the rest of the day.

Starting the meet off strong gets your mind in a good place and a great result there infuses confidence into the following two lifts. Feeling strong also improves your mental game.

On that note, make all versions of your squat the same sort of tone-setter.

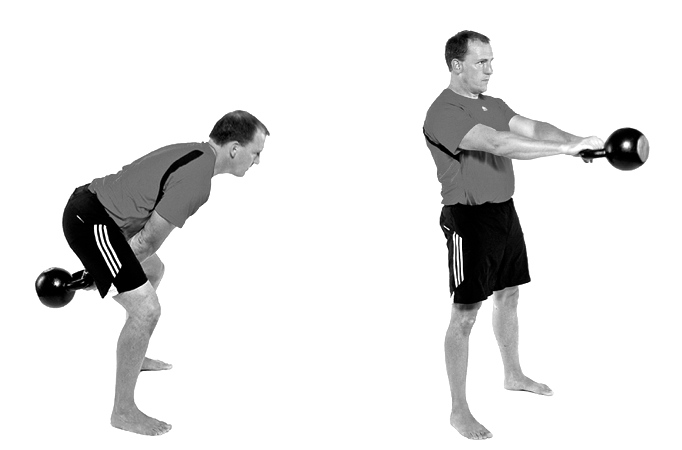

There are so many riffs on the movement: bilateral variations, such as kettlebell goblet squats and barbell front squats, are excellent for targeting anterior core strength, and unilateral variations such as Bulgarian split squats, skater squats, and pistol squats are key for giving both legs the chance to work, and to even out strength imbalances.

These variations are like the sprinkles on a cupcake, though: while I like to sprinkle that ish liberally, I know that these sprinkles alone do not a great, big, fluffy cupcake make.

I acknowledge that I need to work on my similes, but you don’t have to be a powerlifter to embrace cupcakes and the following three lifts, you only have to be interested in improving your strength everywhere—but especially in your core and in the bottom position of a squat. If you are, chances are good that you could give your current back squat PR a nice bump if you incorporate them regularly.

Barbell Squat-To-Box

First things first: what’s the point of having a big squat if it’s not a big, full-range-of-motion squat? Quarter squats don’t count when you’re going for bragging rights.

Depth issues sometimes come down to a lack of awareness in how low you are actually getting.

Heads up: Don’t confuse the Barbell Squat-To-Box with Barbell Box Squats, a variation in which you actually sit on the box. This is a touch-and-go movement and will help you learn what it actually feels like to squat to proper depth.

Zercher Squat

When David Dellanave, owner of The Movement Minneapolis, originally showed me how to do the Zercher squat, I was like, “Really? Why would I want to hold the bar like that?” His answer, “It’s going to get you really f#cking strong, that’s why.”

Zercher squats hammer your quads like crazy, and you’ve never experienced an ab workout quite as intense as a set of heavy Zercher squats. Getting your body strong in weird positions will make lifting in more conventional position that much more lovely.

Zercher squats require that you hold the weight in the crook of your elbows while you complete the movement. The Zercher isn’t just limited to the squat, either: you can also Zercher hold, carry, and deadlift. Because of the position of the weight on your body, this variation is killer for strengthening the upper back.

Hot Tip: Wrap the bar in padding or even a yoga mat for greater comfort.

Pause-in-the-Hole Squat

Many lifters rely on the stretch reflex, that rubber-band-like contraction that happens when the muscles stretch at the bottom of the squat, to bounce out of the hole. There’s nothing inherently wrong with taking advantage of this phenomenon, which is particularly handy when attempting to move the most weight your body can handle.

But, there’s something to be said for eliminating the bounce and building strength from a dead stop in the bottom position.

It means you’ll be less likely to stay stuck in the hole.

Pause-in-the-Hole Squats are a favorite for addressing this issue because your position must inherently stay tight from the top position and hold tight throughout the bottom pause (lest you topple) before driving out of the hole. The extra time under tension will fully hammer home the need to keep the upper back tight and entire core braced, as well as build static strength in the lower back, hips, and abs.

Pausing at the bottom is undeniably challenging, even when your form is shipshape, so lessen the weight accordingly.

About JVB

Jennifer Vogelgesang Blake’s leggings might be pink but her weights aren’t. A personal trainer at The Movement Minneapolis, she is a powerlifting coach and competitor with a passion for helping her clients discover and grow their strength, inside and out. She’s here to spread the good word that strong is empowering and because of that, really, really fun.

Unapologetically Powerful is here!

Are you ready to become Unapologetically Powerful? If you’re even just a little bit interested in improving your back squat, bench press, and deadlift, and building lean, beautiful muscle, you’re going to love digging into this program.

Unapologetically Powerful is your go-to resource to learning all about the “big three” lifts, and removes any intimidation from training for and competing, should you decide to, in the sport of powerlifting.

Trainers Jen Sinkler and JVB have teamed up to provide you the answers to all of your powerlifting questions—and get you radically and unapologetically strong. Here’s what’s in the program:

- A comprehensive training manual that includes Beginner and Early Intermediate 12-week powerlifting programs with a detailed introduction to biofeedback training.

- An extensive guide on how to compete for first-time powerlifters who want to step onto the platform.

- A complete exercise glossary with clear-cut written coaching cues and images.

- A MASSIVE video library of more than 140 exercise demonstration videos. Every movement in the program is in the video library, with detailed coaching cues to walk you through each exercise step by step.

- A revamped version of Lift Weights Faster geared specifically toward powerlifters.

Unapologetically Powerful is on sale for HALF OFF now through midnight Friday, December 11. For more info, click HERE.

Erika Mundinger is a licensed Physical Therapist and a board-certified orthopedic specialist working in the Twin Cities area. She practices orthopedics and sports medicine with advanced training and practice in manual therapies, corrective and functional exercises, and treatment of spinal disorders. She works at TRIA Orthopedic Center, the Twin Cities’ premier ortho clinic, treating athletes from professional to “weekend warrior” levels as well as general orthopedics and is a member of the clinic’s Spine Team, helping to better advance patient access to professionals specialized to manage care of spinal disorders and injury.

Erika Mundinger is a licensed Physical Therapist and a board-certified orthopedic specialist working in the Twin Cities area. She practices orthopedics and sports medicine with advanced training and practice in manual therapies, corrective and functional exercises, and treatment of spinal disorders. She works at TRIA Orthopedic Center, the Twin Cities’ premier ortho clinic, treating athletes from professional to “weekend warrior” levels as well as general orthopedics and is a member of the clinic’s Spine Team, helping to better advance patient access to professionals specialized to manage care of spinal disorders and injury.