I read a recent article by my good friend, Jordan Syatt, on the Personal Trainer Development Center’s website titled No One Ever Got Better Solely From Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercises and I liked it for two reasons:

Photo Credit: Shawn Rossi

1. It’s a message that needed to be said. Breathing drills (and to be more specific, diaphragmatic breathing drills) aren’t going to add 50 lbs to your deadlift, nor improve your vertical jump, and they certainly aren’t the “x-factor” when it comes to improving one’s sex appeal.

Last time I checked no one ever thought to themselves, ” Whoa, that’s one sexy Zone of Apposition goin on there. I need to get naked with that person, like, right now!”

I’m sure there’s someone out there with some sort of creepy ribcage/thorax re-setting fetish, but for the sake of argument lets just agree that breathing drills won’t land you on the cover of People Magazine anytime soon.

2. Jordan gave props to Cressey Sports Performance in the article. What what!

There’s no denying that “breathing” is all the rage right now – especially in the fitness industry. And more to the point, there’s no denying that the peeps over at the Postural Restoration Institute (PRI) are leading the charge.

Funnily enough: while the breathing hype has gained momentum in the last 2-3 years, PRI has been around for DECADES. I guess it just goes to show there’s a tipping point for everything.

I wrote a post a few months ago calling some trainers out who go a little too far down the PRI rabbit hole. I highlighted the fact that I like PRI; I use PRI; I just feel it’s crippling many fitness professionals who take it too far.

One of my biggest pet peeves is when trainers and coaches forget that they’re trainers and coaches and stop training their athletes and clients. Instead they start treating them, which isn’t their scope of practice in the first place. Worse is that their clients rarely (if ever) get a training effect!

I’m sorry but if your client is 30 lbs overweight or just interested in going to a Bootcamp class, they don’t need to be breathing into a balloon for 20 minutes.

Having Said That…..

At CSP, because we work with a lot of athletes who live in a constant state of (spinal) overextension, in addition to general fitness clients who come in with a wide variety of movement dysfunctions, we have found that these drills are a nice fit for our demographic. It’s borderline voo-doo(ish) how much improvement we can glean – both from a postural standpoint and pain reduction standpoint – from having someone focus on their quality of breathing for a few minutes.

There’s a bit of self-auditing required, though. I.e., It’s not going to be an ideal fit for some coaches and trainers.

Take for example a trainer who, while attended mine and Dean Somerset’s workshop in LA last weekend rolled his eyes and made the off-handed comment, “if I did this stuff with my clients, I’d be fired” as I was taking the attendees through a few drills.

1. No shit Sherlock! If the bulk of your clients are celebrities more interested in shadow boxing and looking good for the camera, then of course you’re not going to place a premium on alignment and how breathing mechanics play a role in improving it.

2. So, yeah, placing some emphasis on breathing and breathing mechanics isn’t a good fit depending on who you work with.

Thanks for the insight, dick.

I’ve stated this in the past, but it bears repeating here: GETTING PEOPLE STRONG IS CORRECTIVE!!!!!! This happened to be the larger point I was trying to make which said trainer seemed to overlook. Or maybe he missed it because he was too busy texting on his phone the duration of my presentation.

Okay, okay….not a big deal Tony. You know, people are busy and need to keep in touch with their clients. It’s not th end of the wor…….GODDAMMIT!!!!!! [punches wall].

Why I stress this point is important, because when I do talk about breathing drills and how we incorporate them with our athletes and clients at CSP (regardless of sports played, injury history, and postural imbalances), it’s important to understand that it takes up roughly 2-5% of the total training volume.

That’s it.

Call me crazy, but that’s a pretty awesome minimal investment of time given the profound effects it can have!

Which begs the question: What effects DOES it have?

From my perspective here are a few bullet points.

NOTE: a MAJOR shout out to Michael Mullin, ATC, PTA, PRC, Mind-Jedi Level II for much of what follows. He’s visited the facility a handful of times to enlighten the CSP staff on some PRI basics.

1. Airflow drives the nervous system. More importantly, the respiration you learned about in school is gas exchange. BREATHING is movement.

2. Taking this a step further, much of the advantage of the PRI approach – and why addressing breathing patterns is important – is that it leads to better outcomes for clients and athletes. Teaching and grooving more efficient breathing is every bit as important as teaching and grooving a proper hip hinge or squat pattern.

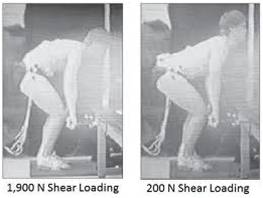

3. People who present with a more scissor posture will have a harder time recruiting and using their diaphragm.

In short, the diaphragm is kind of a big deal, and because many of us are locked into a scissor pattern in conjunction with a left rib flare – what PRI refers to as a Zone of Apposition – we have a hard time breathing correctly.

Ideally the diaphragm will act as a superior and inferior “canister,” descending/compressing when we inhale and elongating/doming out when we exhale….which in turn provides optimal stability up and down the kinetic chain.

Unfortunately, due to the aforementioned scissor posture (to the far right in the pic above), we tend to see more anterior translation of the diaphragm locking us into more extension, which in turn doesn’t allow it to perform optimally.

For the more visual learners out there, here’s how the diaphragm should work:

4. All of this to say: these drills help to “encourage neutral.” The body WILL NEVER by symmetrical due to our anatomy, but when someone lives in extension these drills help to get someone closer.

5. Likewise, the brain wants efficiency and will do whatever it takes to get you there. If you watch how most people stand, they’ll revert to what’s known as a Left AIC (Left Anterior Interior Chain) stance, like this….

The right side of the pelvis will be more internally rotated and ADD-ucted and the left side will be more externally rotated and AB-ucted. This, too, causes all sorts of wackiness and effects posture all up and down the kinetic chain. PRI helps to address this and tries to “encourage neutral.”

6. Lastly, if nothing else, the real benefit to all this is that it helps people to chill the eff out.

Exercise drives the sympathetic nervous system and put people on “alert.” I like to incorporate basic breathing drills to engage the parasympathetic nervous system and help people to tone it back down closer to homeostasis.

In addition, anecdotally, so many people are type-A, live in a sympathetic state, and are always “switched on” that they’re unable to relax. Breathing helps to turn on the parasympathetic nervous system and allows people to smell the roses so-to-speak.

There’s obviously A LOT more to all of this and I’m only scratching the surface with this post. It’s a topic that requires a bit more time (and I encourage you to seek other resources if it interests you). That said, everything I alluded to above hits on a few BIG ROCK points that I hope resonates with everyone.

Whether it’s a good fit for YOU and YOUR clients is a discussion that needs (and should) to be considered. In the end, like anything….it depends