How to Age-Proof Your Program Design Without Watering It down

It’s been awhile since I’ve posted a guest post on this site and I figured it was long overdue.

Today’s post comes courtesy of Austin, TX based trainer and gym owner, Nathan Stowe. Nathan is a long-time friend and colleague of mine who has owned and operated his own jam – HERE – for a number of years. He’s worked predominantly with “older” populations for most of his career and knows a thing or two about how to train and write programs for them without treating them as if they’re going to break their hip just by looking at a barbell.

Age Ain’t Nuthin But a Number

I’ve been working with people over 50 on increasing their longevity for over 16 years—way before it was cool. In fact, Pat Rigsby once told me I might have the strongest solo training business in the country for this demographic…

And when I think about how it all started, it still makes me laugh.

I was only a month into my first personal training job, killing it on the sales floor thanks to my background—then I tore my ACL playing a game of “21” with a buddy. I walked home on it. My friend, ever helpful, said, “Well… maybe I should’ve gone to get the car.”

Silver lining? The injury gave me time to get my NASM Corrective Exercise Specialist cert. I figured I’d pair the education with the experience and become the go-to for banged-up clients.

Plus, the gym paid more per session if you had more certifications—so win-win.

When I came back, I was the “knee guy.”

And in a runner-heavy city like Austin, that meant I got a lot of reps with real clients. I found out fast what worked in the real world… and what was just textbook theory.

One day, my manager asked if I’d work with a client who had a back issue. I said, “Matt, I hurt my knee. I don’t know anything about the back.”

He said, “I know. But I trust you the most to figure it out.”

That line changed my career.

I found a guy online named Eric Cressey—maybe you’ve heard of him?

Note from TG: Never heard of the guy…🙃

I devoured everything he put out and got great results with that client. So Matt gave me a shoulder client next. I told him, “Now that’s even farther from knees.”

Same answer: “I trust you the most to figure it out.”

So I did.

Eric led me to Tony (oh, hello!), Dean Somerset, Mike Robertson, Mike Reinold, Bret Contreras… the Mount Rushmore of evidence-based training for adults who don’t want to live in the PT clinic.

The deeper I dove, the more I realized this was it. I didn’t want to be the guy coaching from 5am–10pm every day. I wanted to be the specialist—the “jacked-up but not giving up” coach. Turns out, that meant working with a lot of adults who were free on Tuesdays at 10am and had real stuff to work around—past injuries, surgeries, chronic pain, or fear from all of the above.

And when you work with enough people like that, you start to notice patterns…

Here are five timeless training techniques I use with every client over 50 to make progress without breakdown—whether they want to deadlift their bodyweight in their 70s or keep jumping in their 70s with Parkinson’s (true story).

1. Use Volume Instead of Intensity As Overload

You’d be shocked how many people stall out (or get hurt) jumping from a 15 lb dumbbell to a 20 lb one. But anyone can go from 1 set to 2 to 3.

Or from 8 reps to 10.

We build strength by layering volume—quietly and safely.

2. Use Range of Motion for Overload

Most people in their 60s are tighter than a snare drum.

Rather than chase perfect form out of the gate, I let ROM be the progression.

Start RDLs mid-thigh → then to the knee → then below the knee → then finally to the floor. Same thing with step-ups or split squats—stack 2 inches of range per month, and in a year they’re moving like they’re 20 years younger.

3. Use Tempo for Overload

You noticing the theme here?

More time under tension = more adaptation without jacking up the weight. We’ll add longer pauses. Slower eccentrics. Controlled transitions.

It builds control, resilience, and confidence—especially in people who feel fragile.

4. Glutes and Abs First. Everything Else Later

We go all-in on glutes and core for six months.

Why?

Because most of my clients come in with knees that feel like cement and glutes that forgot how to contract sometime around 2007.

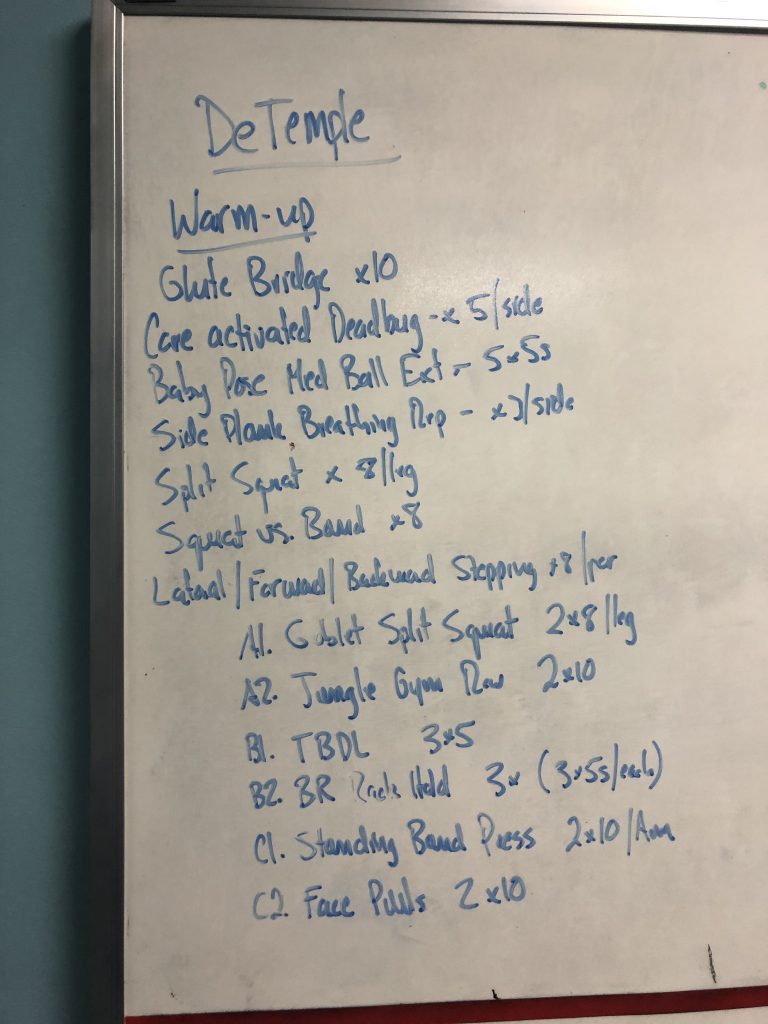

My go-to progression:

Barbell Glute Bridge → Cable Pullthrough → RDL → Rack Pull → Trap Bar Block Pull → Floor Pull → THEN Squats.

All the while? We pair every movement with isometric ab work to control that pelvis and build true trunk control.

5. Push With the Body, Not Against It

Pushups. Landmines. Bands.

Anything that lets the shoulder blades move and the body find its own rhythm.

Once they can do a picture-perfect pushup? Then we talk dumbbells and barbells. I used to have shoulder flare-ups with half my clients by week 12.

Now?

I can’t remember the last time it happened.

These are just five of the tools I use daily. There are at least a dozen more I could list—and if you’re curious, I talk about all of them on my blog at StoweTraining.com.

About the Author

My name is Nathan “Nate” Stowe, and when I’m not being Ella’s dad or Laura’s husband, I dabble in personal training—helping people in Austin, Texas live longer and get stronger. I write daily, so if you liked this, you can find more at StoweTraining.com.