Today’s guest post comes courtesy of strength coach and writer Eric Bach. Eric’s a coach I respect a lot and someone who’s consistently pumping out quality content.

His new resource, The Four Week Power Primer, is on sale starting TODAY.

How Lifters Can Unleash Athletic Power

What You’ll Learn

– Raw Strength isn’t enough.

- You need to generate fast strength via power.

– Lift heavy and lift fast to maximize muscle unit recruitment

– Incorporate bodyweight and explosive, submaximal work.

– You’ll bridge the gap between strength and speed to become a beast!

Here’s the deal:

Most lifters mistakenly think their goal should be getting as strong as humanly possible. Not so. They should focus instead on improving power. This article explains why.

Sure, maximum strength is important. It builds a foundation to train other physical qualities. But there is an added dimension that separates the okay form the elite: Power: or the ability to generate force rapidly.

Athletes in sports other than powerlifting run into time constraints when applying as much force as possible. This results in strength plateaus and poor carryover into sport-specific tasks.

Neglecting power leaves huge performance gaps. It results in athletes who are unable to translate their strength into success on the field.

This Power Primer will show you how to:

* Unlock a nervous system that fires faster

* Create greater levels of useful strength

* Create greater levels of strength

* Improve your ability to generate force

* Rapidly improve your athleticism

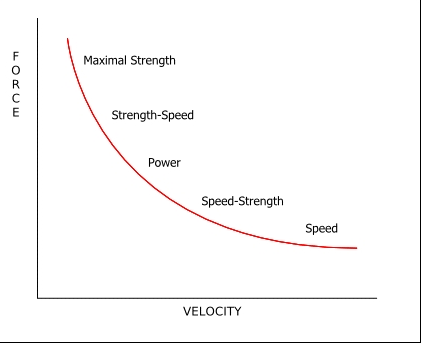

Understanding the Force-Velocity Curve (and Pie)

When looking at the force velocity curve I think of pie (Mmm…pie!)

Maximal strength provides the essential crust. It’s the foundation for a great pie. But you also need finger lickin’ filling, toppings and spices. Think of the fillings, toppings and spices as the ingredients that make the pie unique.

Without the foundational crust a delectable pie isn’t possible. It’s purely mush, much like training for speed and power without a base of strength.

Without careful attention to the other ingredients, there is nothing special about the pie. This is akin to having a base of strength, yet never refining the basic product for maximum performance.

Which brings us to the force velocity curve. It provides a continuum of training for performances and actions that require different speeds against a variety of loads. These could include:

- propelling your body though space

- throwing an opponent to the ground

- engaging in a free for all light-saber battle over that piece of pie

There’s an inverse relationship between load and velocity. The heavier the weight, the slower it moves and the lighter the resistance the faster the speed.

These qualities make up opposite sides of the spectrum, with speed-strength, strength-speed, and power making up the middle of the curve.

Building Explosive Power

Training with a combination of loads improves all-around explosive power, assuming there is a foundational crust of maximal strength.

Unfortunately, most lifters and coaches love hammering huge weights (nuttin’ wrong with that) to the detriment of higher speed movement (something wrong with that.).

This adds adding cheap, canned fillings, toppings, and spices to the pie to an awesome pie crust. Worse still is adding nothing at all. You just end up with the crust.

Stop chasing absolute strength. Most athletes and lifters would derive immediate benefits from lighter, more explosive training that bridges the gap between strength and speed.

Train the factors along the force velocity curve you’ve been neglecting. You will become a more powerful athlete.

That said, you must have a base of maximal strength to develop power.

To maximize power, focus on maximum bar speed with various loads. You will develop strength and speed along the force velocity curve. You will improve your power and your rate of force development. Use heavy weights with fast bursts, such as 3×3 at 90% 1-RM two times per with maximal muscular (2).

Improve Intramuscular and Intermuscular Coordination

Intramuscular coordination is the secret sauce that separates smooth, explosive athletes from rigid, uncoordinated ones. Intramuscular coordination is the coordinated firing of motor units within a single movement.

There are three main components when looking at when looking at improved intramuscular coordination:

There are three main components when looking at when looking at improved intramuscular coordination:

- Rate Coding: The capacity to increase firing rate (motor unit discharge rate) in order to express more strength.

- Recruitment: Recruiting more motor units simultaneously when performing a muscular action.

- Synchronization: The ability of muscle units to contract nearly simultaneously, with very minimal delay.

Through using multiple loads across the force velocity curve we’re able to improve intramuscular coordination. In time, this teaches the nervous system to recruit fewer motor units for the same relative intensity.

More motor units are available for activation for higher intensity exercise. That could translate into more weight on the bar or a faster sprinting speed.

How to Generate Maximum Force When Lifting

Few things, except coming home with the pie you’ve been eyeballing all night, are as fun as lifting maximal weights.

That said, too much pie (and maximal weights) isn’t good either.

Except for the rare genetic elite, your nervous system, joints, and tissues will scream at you before too long. Luckily, there are two ways to maximize force when lifting:

- Lift heavier weights

- Lift lighter weights (or your body) faster

Lift compound movements like squats and deadlifts as fast as possible, while still controlling each rep during the eccentric. By moving weights as fast and as hard as possible, you’ll recruit a greater number of muscle fibers for more muscle growth. You’ll also maximize nervous system recruitment for greater performance.

Submaximal Weight Training

Speed-Strength exercises, like sub-maximal lifting, result in high power outputs.

They produce super-high power outputs compared to longer duration, lower velocity max strength exercises.

Compare a tractor-trailer and a Ferrari. It’s great to have a ton of horsepower, but for high-performance it’s best to generate horsepower rapidly.

Power= Work/Time

In this case, explosive exercises are best using loads between 20%-85% for multiple low-rep sets is best (1). If I were a betting man, I’d wager you’re already using a sub-maximal squat day plus multiple warm-up sets between 50-80% 1-rm.

If you’re warming up like a good lad, you’re already getting some volume within the strength-speed realm.

Here’s the Kicker:

The missing piece is lighter, more explosive work.

Speed-strength movements will address this with high-velocity movements movement against a small external load. Exercises like the jump squat, back toss, and overhead slam train an explosive transition from eccentric-to concentric against a light load.

For the athlete or lifter, this requires practicing a specific movement (intermuscular coordination) patterns for optimal transfer.

For example:

Athlete Movement: Triple Extension in sprinting

Training Movements: Resisted sprinting, clean, squat jump

Or…

Athlete movement: Powerlifting Squat

Training movement: Barbell jump squat

To maximize the benefits of intramuscular coordination, exercises of mechanical demands should be practiced with various loads to improve the efficiency of the nervous system.

In time, this teaches the nervous system to recruit fewer motor units for the same relative intensity.

How to Immediately Improve Your Power

Provided you already have your foundation of strength, you can rapidly improve your power with a few tweaks to your training.

First, you need to continue training with heavy, multi-joint exercises and explosive intent on reach rep. This maximizes motor unit recruitment, improving RFD.

Second, when warming up accelerate every rep to the best of your ability. This trains in the strength-speed and speed-strength portion of the force velocity curve, specifically with loads between 20-80%.

Third, incorporate light speed, and speed-strength training methods with low-movement load (0-20%) and high-speeds. This comes in the form of jumps, sprints, throws, and other upper/lower body plyometrics.

Fourth, match the explosive movement patterns used to the movements you’re looking to improve using post-activation potentiation (PAP).

PAP, although an advanced method, uses the biomechanically similar exercises to groove explosive movement patterns after a heavy strength exercise.

For Geeks Only: How Does it Work? (Pie-Loving Regular People Can Feel Free To Skip this Section)

According to Hamada et. el (2000), there is an increased phosphorylation of myosin regulatory light chains during a maximum voluntary contraction (MVC). This allows the actin and myosin binding (for muscle contraction) to react to the increased calcium release. This reaction triggers a cascade of events leading to enhanced force muscle production at the structural level of muscle (Horwath & Kravitz ).

Thus, increased muscle activation yields a greater duration of calcium ions in the muscle cell environment, yielding a greater phosphorylation of the myosin light chain protein (Rixon et al. 2007).

The second theory is based on the H-reflex, an excitation of a spinal reflex elicited by afferent muscle nerves. It is theorized that the PAP intervention enhances the H-reflex, thus increasing the efficiency and rate of the nerve impulses to the muscle (Hodgson, Docherty, Robbins, 2005). Your nervous system get’s jacked up full-go.

When a jump is performed, your body is prepared to fire on all cylinders. So when only your body weight is used, the over-stimulated nervous system and muscles will be primed to the max for a higher jump.

Here are some Common Pairings:

Main Exercise: Explosive Movement:

Bench Press Clap Push Up, bench plyo push up

Shoulder Press Overhead medicine ball slam/ throw

Squat Jump squat, vertical jump, box jump

Deadlift Broad jump, kettlebell swing

What to do: Pick an explosive exercise that matches the movement pattern of your main lift and perform 3-5 reps immediately after your pure strength movement. Rest 2-3 minutes between sets to achieve a PAP effect

Wrap Up

Most lifters plateau in the gym and stay mediocre because they continue doing what they’ve always done in the past. They lift only heavy and focus only on the weight or muscle. They neglect rep quality and explosiveness. This mistaken approach is not performance training.

A solid strength foundation remains essential. Build on that foundation to focus on:

* quality explosive reps to improve neuromuscular performance

* rep speed

* movement quality over quantity

Now, It’s Time to Put the Plan to Action:

If you’re looking for a short-term plan of attack to improve your strength and athletic performance, then check my resource the Four Week Power Primer. It’s a four-week plan to increase your power for bigger numbers in the gym, and better performance on the playing field.

If you’re a coach, you should absolutely own this to understand the science of power, as it’s loaded with the science behind improving performance.

If you’re a meathead just looking to add some strength to the bar, then great: This could be the missing component holding you back from smashing a new PR.

Seriously, don’t wait, because the chance won’t be available for long.

Grab the Power Primer during the limited time sale, and leave Eric any questions you have below.

—> Power Primer <—

Resources and Stuff

Horwath, R., & Kravitz , L. (n.d.). postactivation potentiation: A brief review. Informally published manuscript, Exercise Science , Retrieved from http://www.unm.edu/~lkravitz/Article folder/postactivationUNM.html

Rixon KP, Lamont HS, Bemben M. Influence of type of muscle contraction, gender, and lifting experience on postactivation potentiation performance. J Strength Cond Res. 2007; 21: 500–505.

Robbins, D.W. Postactivation potentiation and its practical applicability: a brief review. J Strength Cond Res. 2005, 19(2): 453-458.