When you see the name Elon Musk it’s a safe bet adjectives like “smart,” “intelligent,” and “revolutionary” come to mind. Jason Bourne? “Badass,” or maybe “guy I wouldn’t want to pick a fight with.”

Meghan Callaway?

Well, if you ask me, when I see the name Meghan Callaway I think “amazing coach and the World’s #1 ranked pull-up connoisseur.”

To put it lightly: Meghan likes pull-ups.

She likes them a lot.

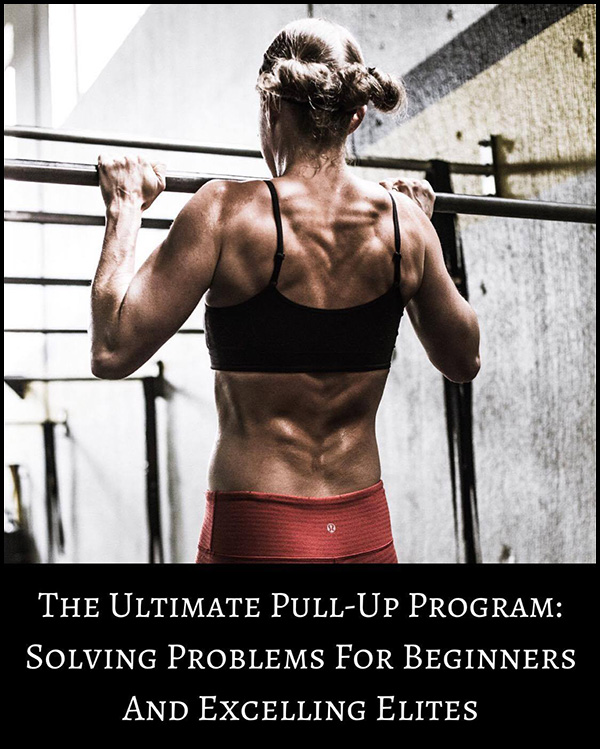

And, to speak truthfully, there aren’t many coaches I’d tip the hat to when it comes to pull-up mastery and programming than Meghan. She consistently impresses me with her content and knowledge on the topic, and as it happens she just released her latest resource, The Ultimate Pull-Up Program, today.

If you struggle with the pull-up and/or are looking for a little direction on how to become more proficient with them (not to mention learning a TON of awesome variations) than I can’t recommend this resource enough. It’s on sale this week at $50 off the regular price for this week only.

3 Unique Drills to Help You Conquer Your First Pullup

Performing your first pull-up is a unique experience.

In fact, when many people conquer their first pull-up and get their chin over the bar (of course without straining their neck to do so), they often experience far greater feelings of empowerment, accomplishment, and downright badassery than when they hit PR’s on max deadlifts, squats, and other heavy meat and potatoes exercises.

Meghan showing off.

Maybe I’m a little biased, but with pull-ups it is just different.

When it comes to tackling pull-ups, many people quit long before they’ve achieved their first rep. Others hit their first rep but are never able to string together multiple reps and become frustrated.

Let me tell you, it does not have to be this way.

In most cases, people fail to reach their pull-up goals not because they are weak, but because they are not training for the exercise the right way.

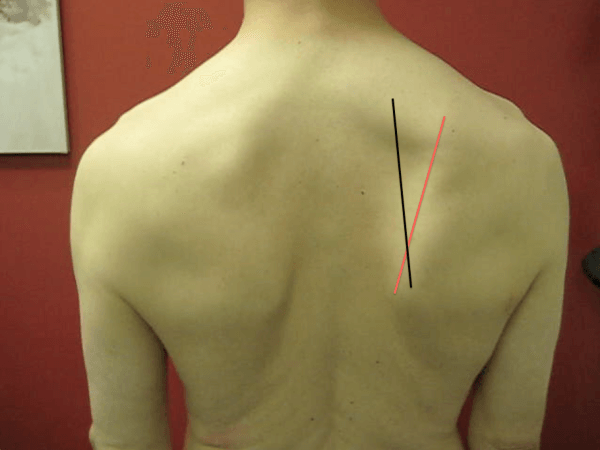

Many people possess enough upper body strength that they should be able to do pull-ups, but they often suffer from technical deficiencies. Other people know what to do but they do not possess the requisite levels of lumbo-pelvic stability or the ability to control the movement of their shoulder blades.

So essentially, instead of moving a stable object to and from the bar in a shorter and more efficient straight line, they are forced to move a heavy, floppy and limp body to and from the bar and in a longer and inefficient arc. Kind of like Erick here. Tony likes cats so I know he understands.

In this article I will provide some of my favorite exercises that address various areas that are holding many people back from performing their first pull-up ever, or from performing multiple reps and feeling like a total badass, or perhaps Wonder Woman.

Without further ado, here are some of my go-to exercises for conquering the pull-up.

1) Scapula Pull-Ups

If you cannot hang from the bar or control the movement of your shoulder blades, you will not be able to perform a pull-up.

This exercise will help lead you to your first pull-up as it develops grip strength, scapular and shoulder controlled mobility, and lumbo-pelvic stability.

While this is a pull-up regression, it is a definite stepping stone towards doing your first pull-up. If you are performing this exercise correctly, the muscles in your mid and upper back, not your arms, should be doing the majority of the work.

Key Coaching Cues:

- Grab onto the bar so your palms are facing away from you and are slightly greater than shoulder width apart.

- Before you perform your first rep, make your body as stable as possible by bracing your core, tucking your ribs towards your hips (closing the space in your midsection), squeezing your glutes, straightening your knees/flexing your quads and hamstrings, and dorsiflexing your feet. This will stabilize your pelvis, spine, and legs, and will prevent your body from swinging.

- In terms of the pull-up, without bending your elbows or initiating the movement with your arms, use the muscles in your shoulder blade area and draw your shoulder blades together and down (bring each shoulder blade in towards your spine and down towards your opposite hip), and lift your body a few inches. Pause in the top position, really contract these muscles, and lower yourself to the starting position in a controlled manner. Fully extend, but do not hyperextend your elbows.

- On the lowering portion of this movement, your shoulder blades will perform the reverse movements as they did on the way up.

- Do not allow your lower back to hyperextend or ribcage to flare. Keep your chin tucked and neck in a neutral position.

- As for your breathing, exhale just after you have initiated the scapular movement and have drawn your shoulder blades together and down; inhale and “reset” as you are descending, or do a full reset when you are in the bottom position.

2) Pull-Up Regression: Eccentric Pull-Ups (from a bench)

Many people falsely assume that when they have accomplished the awesome task of “pulling” their body to the bar their job is done, and they allow their body to free-fall to the bottom position with reckless abandon.

This exercise will help you improve your pull-up technique (lowering component), and develops upper body strength, grip strength, scapular and shoulder controlled mobility, and lumbo-pelvic stability.

Owning the ability to lower your body with control and ease will make your transition into the next rep much more seamless, and will thus improve your ability to perform multiple reps.

Key Coaching Cues:

- Grab onto the bar so your palms are facing away from you and are slightly greater than shoulder width apart.

- Stand on a bench or box so your chin is already at (or close to) the height of the bar. Or if you are already able to, jump from the floor and pull yourself up the rest of the way by using the muscles in your mid and upper back and drawing your shoulder blades together and down (bring each shoulder blade in towards your spine and down towards your opposite hip). Do not initiate the movement with your arms.

- When your reach the top position, it is important that you stabilize your body as quickly as possible as this will prevent your body from swinging back and forth and will allow you to focus on the lowering portion of the exercise. You will achieve this full body stability by taking a deep breath in through your nose (360 degrees of air around your spine), bracing your core, tucking your ribs towards your hips, squeezing your glutes, straightening your knees/flexing your quads and hamstrings, and dorsiflexing your feet.

- Repeat the breathing, bracing, and rib tuck that I described above; now perform the eccentric movement and slowly lower yourself down to the bottom position in 3-5 seconds. Use the muscles in your mid and upper back, anterior core, glutes, and legs to control the movement. Your shoulder blades should move in a controlled manner. Do not allow your lower back to hyperextend or ribcage to flare. Keep your chin tucked and neck in a neutral position.

- Let me reiterate that this exercise is not for the arms. The muscles in your mid and upper back should be performing the vast majority of the work, and the muscles of your anterior core, glutes and legs will help keep your body in a stable position.

3) Dead Bugs With Double Kettlebell Resistance

A huge number of people fail to excel at the pull-up because they treat it like an upper body exercise when in fact it is a full body exercise that demands a lot of lumbo-pelvic stability.

This bang for your buck dead bug variation accomplishes just that, and helps you develop the necessary level of tension that is requisite to optimal pull-up performance. This exercise also develops scapular and shoulder controlled mobility.

Key Coaching Tips:

- Lie on the floor. Grab onto two kettlebells or dumbbells, and extend your arms so they are in a vertical position, and so your hands are above your chest.

- Lift up your legs so they are in a vertical position, straighten your knees, and point your feet toward you (dorsiflex). Keep your chin tucked and neck in a neutral position.

- Before you go, take a deep breath in through your nose (360 degrees of air around your spine), and tuck your ribs towards your hips. Now forcefully exhale through your teeth, contract your anterior core muscles as hard as you can (10), and slowly lower the kettlebells and one leg towards the floor and to a range where you can maintain proper form. Return to the starting position. Reset and repeat with the opposite leg.

- Make sure you don’t allow your ribcage to flare or lower back to hyperextend.

- Keep your legs relaxed so they do not dominate.

- Make sure that your knee remains in a fixed position and that the movement occurs from your hip.

- One key I like to look for is that if your shirt is wrinkled it likely means your ribs are in the right position. If your shirt suddenly becomes smooth, you have likely disengaged the muscles in your anterior core and have flared your ribcage. This defeats the purpose of the exercise.

Now that I have given you some extremely useful exercises that will help you accomplish your first pull-up ever, or several consecutive reps, it’s time to let the cat out of the bag and get started on achieving this amazing goal. Apologies for the cat references, but my cat is snoring while I’m trying to write this.

The Ultimate Pull-Up Program

Whether you’re male, female, Klingon, whatever….getter better at pull-ups is never a bad option and will almost always carryover to other endeavors you pursue inside the weight room (and out).

- Improved ability to squat and deadlift a metric shit-ton of weight? Check.

- Improved body composition? Check.

- Harder to kill as a whole, especially during the impending zombie apocalypse? Check.

This is undoubtedly one of the best resources on the topic I have ever come across. If you’re looking to up your pull-up game you’d be hard pressed to find a more thorough resource.