People are often surprised when I state I’m an introvert.

What most people fail to recognize is that “being an introvert” is part of a spectrum. No one is 100% introverted, nor are they 100% extroverted.

Everyone’s a little of both.

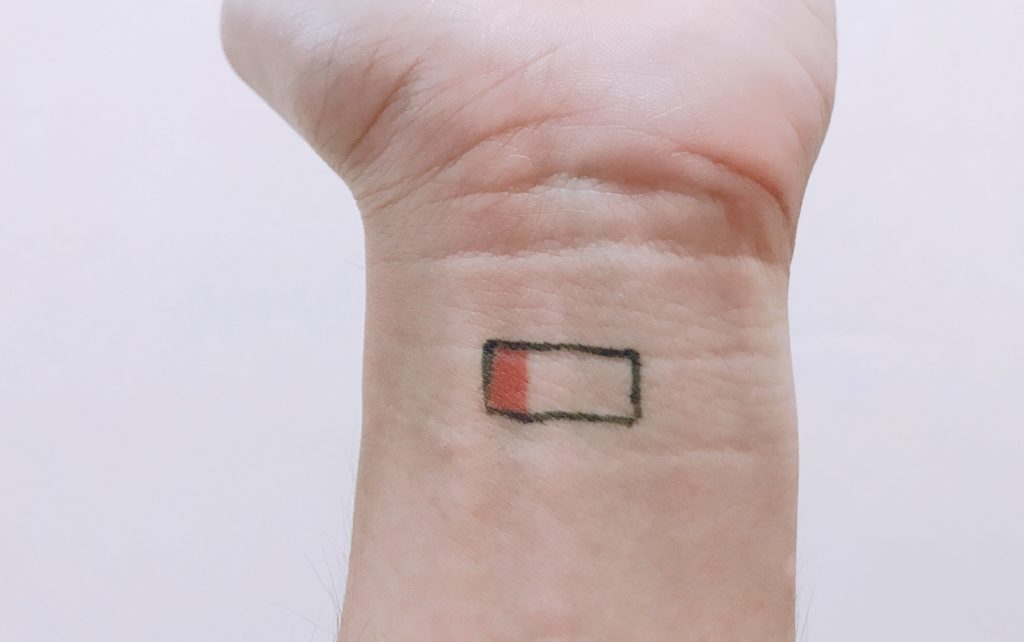

Another common misconception is that introversion is somehow correlated with being depressed or sad or downtrodden. In attempting to find a suitable image to go along with this post I simply typed “introvert” into my image finder thingamajiggy on WordPress and was quite surprised (if not slightly appalled) by what appeared on my screen:

Image after image after image of various people looking dejected, anti-social, and altogether unhappy.

It was quite striking, because all “being introverted” means is that you likely need or require a little more down time (or down tempo activities) in order to reenergize and recharge.

I remember when my wife and I first started dating there was a night where I had just gotten back from a full day of coaching and was zapped. All I wanted to do was collapse on the couch and watch House Hunters. Unfortunately (for me) it was a Saturday night and Lisa had already committed us to a get together with a bunch of her friends at a local lounge in downtown Boston.

Ten minutes in it took all the will-power I could muster to not walk out of the place and straight into the path of the #66 bus down the street.

I just stood there with a blank stare and repeated one word answers as she and her friends attempted to engage with me.

- “Tony, Lisa tells me you’re a personal trainer?” Yes.

- “How long have you been doing that?” Awhile.

- “So, what do you think about keto?” Grabs beer bottle, breaks it over the counter, slits own throat.

When we eventually left we had one of our first arguments. Clearly I was acting like an a-hole, but after explaining to her that the last thing I wanted to do after coaching for eight hours was to go to a bar and listen to Panic! At the Disco, we had a better understanding of each other’s needs.

I explained I am not against going out and participating in social events, I just needed a bit of a “buffer.”

Being a coach – inundated with constant noise and non-stop interaction – can be draining.

An introvert requires the antithesis of that in order to feel rejuvenated and ready to go the following day.

To repeat: This doesn’t mean we don’t like to do or be involved in social activities.

Rather, in our free time we generally prefer to:

✅ Read a book

✅ Enjoy a barrage of kitty cuddles.

That’s pretty much it.

One common remark I receive from other coaches and personal trainers is what would I recommend they do to counteract their juices running on empty when they’re in the middle of a long work day?

What can they do when they’re five hours deep into a long work day and have a barrage of sessions yet to complete? It’s not like they can meander off into a hidden closet and take a power nap.

(or can they?????)

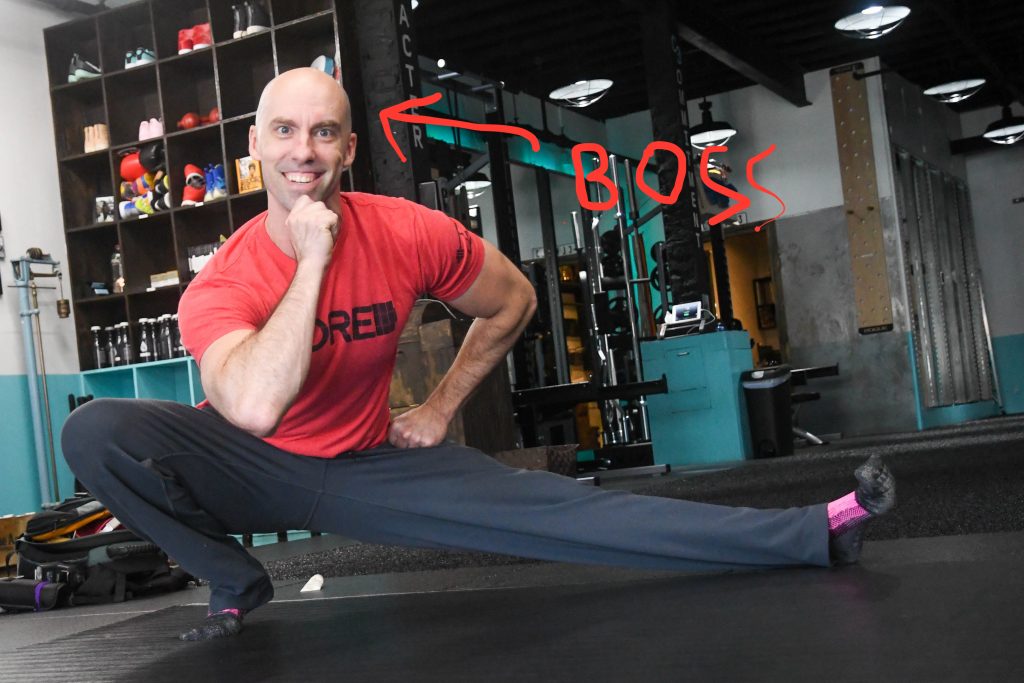

Likewise, is the expectation that we have to be the rah-rah, high-energy coach who jumps up and down everywhere and perform cart-wheels after every set in order to be considered “good” or successful?

Listen, the bulk of your clients aren’t expecting a Bad Bunny performance during their session.

Sure, there’s a time & place to amp things up and to be the cheerleader, but I’ve found that more often than not…

…most clients don’t care for the (fake) performative nonsense.

You can still be a switched on and attentive coach without the theatrics.

That being said, it still behooves you, introverted coach, to be proactive and give yourself sporadic breaks throughout the day. These could be brief 15-30 minute windows of solitude when you know you have a full-day looming. Or, when you know you have a solid line-up of clients scheduled, it may be worthwhile to break the day up where you get your own training session in half way through.

BUT MOST IMPORTANT OF ALL: Do NOT fall pray to this idea you have to be a performative coach in order to be seen as legit. That BS may get you likes on Instagram, but it’ll lead to nothing but eye-rolls in the real world. Not to mention it certainly won’t be doing you any favors from an energy conservation standpoint.1

BUT EVEN MOST MOST IMPORTANT OF ALL: Be sure to grace yourself with ample “me time” when you feel you need it. This could be sitting at home binging a show, going to the movies, hanging out at a bookstore of coffee shop, or, I don’t know, perusing your baseball card collection.

Remember: All being an introvert means is that you’re a fucking psychopath you likely require more solo time in order to reenergize.

It’s important to lean into it.

It’ll help make you a more engaged coach and your clients will benefit as well.

So, hi fellow introvert. I see you. What’s up?