Greetings from Cortland, NY!

It’s freaking snowing (not that that’s any big surprise)! That would be like saying,”the sky is blue,” or “water is wet,” or “Justin Beiber is a no-talent ass hat!”

I left Boston yesterday under blue skies and 60 degree weather (which feels like summer this time of year), only to arrive in central NY five hours later to overcast gloom and nothing but rain and snow.

Welcome home, Tony!

Despite the really crappy weather, it is nice to be “home.” I placed home in quotations because the college is literally ten minutes from my home town, and part of the impetus for making the trip – other than the non-stop adulation, praise, and ticker tape parade that may or may not happen in my honor – was to be here for Easter and take advantage of Mama Gentilcore’s home cooking.

Which is to say: I absolutely crushed some apple pie yesterday.

Nevertheless, to say it was an honor to be asked to come back and speak would be an understatement.

Note: for those out of loop: I was invited back to my alma mater to speak to some of the Exercise Science, Kinesiology, and Fitness Development majors; as well as any graduate students or general public you didn’t want to watch Dancing With the Stars and come listen to me speak instead.

In fact, it’s been kind of a surreal experience.

I mean, back in the day, when I was an undergrad myself, I was about as nondescript of a student as they come. And now, I’m expecting upwards of 50+ people to show up just to listen to me speak. Unreal.

Everything started to kick into high-gear when, last week, THIS short write up popped up on the school’s homepage detailing (the Cliff Notes version anyways), what I’ve been up to in the year’s since I graduated, as well as giving people a sneak peak into the topic of my presentation, which I’ll be throwing down later today.

From there it’s been an avalanche of local media exposure. I got a call from the school newspaper asking if we could set up a time for some photo ops, and then a local news talk radio station (in Ithaca) contacted me and wanted to do a 5-10 minute interview LIVE for their morning show.

And when I say live, I mean literally – LIVE. I called in and the guy was like, “we’re on in 30 seconds!” Thankfully everything went smoothy and I didn’t drop an f-bomb. Woo-hoo!

Afterwards I got in my car to make the quick trip to the main campus where the game plan was to speak to a Kinesiology class (the class of the professor who set this whole shindig up). The vast majority of the kids in the class were aspiring personal trainers, coaches, and future business owners, so rather than stand there and bore them to tears talking about insertions and origins and blah blah blah, I wanted to take the time to impress upon them some of the traits and characteristics that I feel every fitness professional should strive for.

Namely, that success in this industry isn’t so much dictated by book smarts or just showing up to class – but rather, it’s about having an insatiable drive to always make yourself better, and that at the end of the day it’s important to understand that you’re not that big of a deal and that you need to put your work in just like everyone else.

Here are some of the main bullet points I hammered (within 50 minutes):

1. Do you see this as a career or a hobby? First and foremost you need to get comfortable feeling uncomfortable, because you’re not going to know the answer to everything. But those who deem this more of a career, and something that they see as their future, will always try to find the answer and get better.

2. Understand that you (probably) won’t make a lot of money right out of the gate. Visions of a six-figure salary and having a ton of disposable income is wishful thinking. Statistically speaking most trainers burn out within two years, which isn’t surprising when you factor in 10-14 hour work day, 6-7 days per week. Likewise, most trainers are NOT financially independent, work pay check to pay check, and often have to get a second job to make ends meet.

The point isn’t to be a Debbie Downer or to say that it isn’t possible to do very well for yourself. But, if we’re going to be honest, and if we’re really going to prepare people for the “read world,” then this is the kind of stuff upcoming trainers and coaches need to hear.

3. Don’t have more degrees than a thermometer. HA – get it!?!?!? Degrees? Thermometer? Okay, I’ll shut up.

An example would be Joe Schmo, MSc, CSCS, CPT, LMT, Who gives a s***.

Point blank, no one cares how many letters you have next to your name. It doesn’t really mean anything. Sure it looks cool and it will undoubtedly help open the doors to a few more opportunities, but it always comes down to a quote I’ve heard Mike Boyls state time and time again:

No one cares how much you know, until they know how much you care.

4. I gave a quick quiz to the students, and asked how many could:

– Name all four muscles of the rotator cuff. Which ones are external rotators?

– What’s the main function of the rotator cuff?

– Name 8 out of 17 muscles that attach to the scapulae?

– Name the only hip flexor which acts above 90 degrees of hip flexion?

– Explain the difference between a short and stiff muscle?

– Coach someone how to deadlift properly?

– Explain to a normal person why there’s no such thing as a “Fat Burning Zone?”

– Draw the Kreb’s Cycle. Blindfolded.

Okay, kidding on that last one.

But the point was – can they actually explain these basic things? If not, well………..what does that say about this being a hobby or a career?

5. Learn functional anatomy. Not everyone is going to be an anatomy cyborg like Eric Cressey, Mike Robertson, or Bret Contreras. But it stands to reason that knowing your way around the human body is kind of an important trait to have as a fitness professional.

Admittedly, while I can get by and I can hold my own, anatomy is NOT one of my strong suits. What’s important, and something I stressed to the students, is that it comes down to repeated exposures. You’re not going to learn everything overnight, and if you hang out around the likes of Bill Hartman you can’t help but feel stupid at times.

The omohyoid thingamjiggy does what now?

Read blogs, articles, and books. Watch DVDs. The more repeated exposures you give yourself to any given topic, the more likely, someday, the light bulb will go off.

Trust me: it happens.

6. Be PROACTIVE as a coach! Actually look like you give a shit! Don’t just stand there and look like a zombie and count reps. COACH your clients.

7. But at the same time, don’t overcoach. Someone’s squat may look like a train wreck waiting to happen and you may very well want to throw your face into a wall, but it’s important not to overwhelm someone and to learn to focus on 1-2 major things rathe than trying to perform a miracle.

8. Try not to fall into being part of the status quo. Don’t throw in all the “smoke and mirrors” into your programming for the sole purpose of looking different than everyone else. Get people results, get them feeling better and moving more efficiently, and you’ll be doing your job.

9. I feel EVERY upcoming trainer should spend at least 1-3 years working in a commercial gym setting. Sure you’re going to have to fight the urge to pour battery acid in your eyes or to swallow live bees from all the asinine things you’ll see……but it’s one of the best ways to get better. In what other setting will you have access to such a wide variety of clientele? If you can teach a 45 year old CEO with the movement quality of an iceberg how to deadlift, you can teach anyone how to deadlift.

Sure you’re going to have life-sucking clients that will zap all your energy, but those are few and far between. Having the opportunity to work with such a wide variety of backgrounds, goals, needs, injuries, etc will speak volumes as far as making you a better coach.

10. Watch your social networking. As a potential future employer, I can guarantee you that if you apply for an internship or job, we’re checking your Facebook and/or Twitter accounts.

You know all those pictures you have up from when you won that Beer Pong championship back in 2012? Or all those posts where you called your ex-girlfriend every colorful name under the sun? Yeah, you should probably take those down.

And those were just the tip of the iceberg. I had a few other points that I made, but I feel like I’m just blabbering on now.

Anyhoo, the main show starts at 5 PM where I’m going to speak to a much larger crowd on things like assessment, program design, the season finale of The Walking Dead, and I’m sure I’ll go on a few rants or two. Or three.

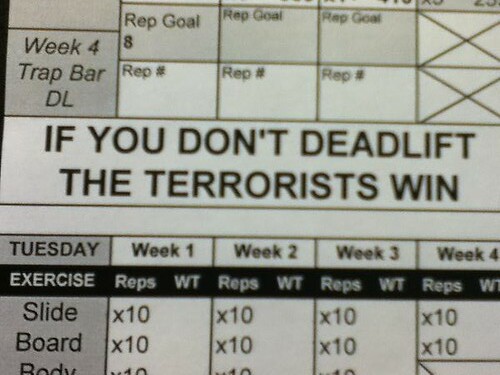

Until then I need to get rid of some pent up nervousness and go lift some heavy things. Might as well go deadlift – of course!

Wish me luck……;o)

More and more (especially with our baseball guys, but even in the general population as well) we’re seeing guys walk in with overly depressed shoulders. For visual reference, cue picture to the right.

More and more (especially with our baseball guys, but even in the general population as well) we’re seeing guys walk in with overly depressed shoulders. For visual reference, cue picture to the right.

body part per day split. Chest day, back day, blah blah blah. Trust me, a little piece of my soul dies just thinking about it. I can’t even begin to tell you how much I cringe looking back at how I trained as a high school and even collegiate athlete. If I ever had the chance to take a time machine back to 1994, I’d totally go back and Sparta kick myself in the face.

body part per day split. Chest day, back day, blah blah blah. Trust me, a little piece of my soul dies just thinking about it. I can’t even begin to tell you how much I cringe looking back at how I trained as a high school and even collegiate athlete. If I ever had the chance to take a time machine back to 1994, I’d totally go back and Sparta kick myself in the face.