I’m traveling back to Boston today after spending the weekend up in Edmonton with Dean Somerset teaching our Complete Shoulder & Hip Workshop.

FYI: Future Dates: ST. LOUIS (September 26th-27th), CHICAGO (October 17th-18th), and LOS ANGELES (November 14-15th).

It was an awesome two days and we were ecstatic to have the opportunity to share our new material with a bunch of personal trainers and coaches eager to geek out over everything shoulders and hips (and my lame cat jokes).

The highlight, though, had to be me admitting to the audience (full of Canadiens, mind you) I’ve never been to a hockey game. Like, ever. You could factor that and then imagine any number of other awkward scenarios – farting in an elevator, being on a first date and realizing you forgot your wallet, that part in Star Wars when Luke and Leia kiss (and then, fast forward to Return of the Jedi, and you realize that they realize they’re brother and sister) – and none of that can top the awkward concert of crickets chirping which occurred.

Okay, it wasn’t that awkward. But I did get a few “what chu talkin’ bout Willis” looks.

.

.

Nevertheless I’m out of the loop today, but have an awesome guest post by DC-based strength coach, Kelsey Reed, on the topic of joint laxity and hypermobility.

Enjoy!

Training With Laxity

Cue a bunch of crickets chirping and then

Want to see a strength coach party trick?

I have a fair amount of joint laxity and amongst coaches and trainers this stunt usually produces a few raised eyebrows and surprised looks. Amongst normal people, they just stare blankly at me and wonder why would anyone bother to do a squat facing the wall.

Joint hypermobility or joint laxity (the terms are used interchangeably) is the ability of a joint to move beyond the usual range of motion. Typically this is because the ligaments are looser than “normal” the due to either genetics or injury.

For the most part, joint laxity isn’t debilitating nor is it usually a worrisome problem, particularly if you’re a gymnast, dancer, baseball pitcher, or a Cirque du Soleil performer.

However, if you are a lax athlete/trainee there are some training considerations to keep in mind. It’s easy to inadvertently injure yourself or cause chronic aches and pains.

Before we dive into some recommendations, are you someone with joint laxity?

The most common test for generalized joint hypermobility is the Beighton Scale.

If you can do at least 2 or 3 (sources differ), then it’s an indicator that you may have general joint hypermobility. Don’t freak out; like I said hypermobility is very common, particularly among children and adolescents (though many grow out of it later), females, Asian, and Afro-Carribbean races. Laxity can manifest in a variety of ways with differing levels of severity. It also isn’t necessarily systemic; it can affect some joints and not others.

If it’s so common, why do we need to worry about it?

According to Dr. Hakim over at Hypermobility.org:

“However some hypermobile people can injure their joints, ligaments, tendons and other ‘soft tissues’ around joints. This is because the joints twist or over extend easily, may partially dislocate (or ‘sublux’), or in a few cases may actually dislocate. These injuries may cause immediate ‘acute’ pain and sometimes also lead to longer-term ‘chronic’ pain.”

I would also add that being hypermobile or lax will also increase the chance that joints will be unstable and therefore exercises that focus on stability will be key to maintaining healthy joints. Additionally, the end-range of motion of joints will be the soft tissue instead of the bones; you could easily stress and irritate the ligaments and tendons during lock-outs. (More on that below)

Since there is a slightly higher risk for injury for us lax people, here are some of my thoughts when it comes to training.

Be Mindful of Joint Position During Exercise

Just because your joints can go through a full range of motion, doesn’t mean that it’s necessary. For example, look at my elbows at the top of a push up:

I catch a lot of my females doing this and I coach them to leave a little slack in the lock-out. Their arms are still straight, just not pushed to the very end of their range.

Here’s another common position lax people can fall into:

In this position, I’m not really “owning” it but instead I’m relying on all my passive restraints (the ligaments) to keep my body stable. Notice the excessive arch in my lower back, my shoulder blade sticking up like Mt. Doom, and my elbow popping forward beyond my wrist.

I would argue that this position offers a false sense of stability and, as the weight increases, it’s going to become harder and harder to stabilize and eventually something will start hurting.

Here’s where they should be:

Here, I’m actively stabilizing by using the surrounding muscles- my core, upper back, and the triceps/biceps of my support arm- it’s safer and more effective in the long run.

Placing the ligaments and tendons under load while pushing through to the end range of their movement is a recipe for achy joints. Be aware of how you/your clients are performing various exercises and own the range of motion- you should be stable and strong, not loose and wobbly.

Balance Distraction and Approximation Exercises

Simply, distraction exercises pull the joints apart, as in a pull-up, and approximation exercises push the joints together, as in a push up. People with hypermobility are going to be more sensitive to the external forces placed on their joints.

For example, I experienced some wicked elbow pain last year.

I was mystified – I wasn’t benching too much or doing hundreds of skull crushers and curls, all the no-nos when it comes to cranky elbows. I took a gander at my weekly training routine at the time, and in an effort to increase my deadlift, I was deadlifting, pull-upping, kettlebell swinging, and rowing nearly every day; I did push ups a few times a week, but aside from that, I didn’t include any pressing.

The former exercises are all fantastic in themselves yet they’re all distraction. I had triple (if not more) the volume of distraction as I did approximation exercises. I subbed out a few of the pull-ups and rows for pressing and, surprise! My elbows felt much better.

When performing exercises that are distraction, pull-ups, row variations, and even deadlifts to an extent, it’s best to avoid the “dead hang” position (when you’re fighting gravity by hanging on your passive restraints instead of actively holding the bar/weight). If the stress is placed on the joints without the accompanying muscle activation, all that tension goes straight into the tendons and ligaments (when I hang from a bar, I can literally feel my forearm bones separating from my upper arm). By creating muscular tension when holding onto the weight or bar, it will prevent excessive stress for your poor ligaments.

Stop, for the Love of Iron, Stretching!

We humans like to do what we’re good at and if you’re hypermobile, you’re good at stretching. Hypermobile people need stretching as much as Darth Vader needs a haircut.

If you feel tight, it’s probably because that muscle(s) is fighting to hold your joints together because your tendons are loose. At best, stretching is only going to feed into the dysfunction (if there is one). We need to stabilize! Which rolls nicely into the last point…

Note From TG: HERE’s an article I wrote on why “stretching” isn’t always the answer.

Stabilize

It’s not cool or sexy but it’s darn useful! If you’re hypermobile, there’s a chance that the ligaments in your spine are too. No good, my friend. Planks, deadbugs, bird dogs, are examples of stabilization exercises that focus on the smaller, lower threshold muscles that are necessary for happy spines and joints.

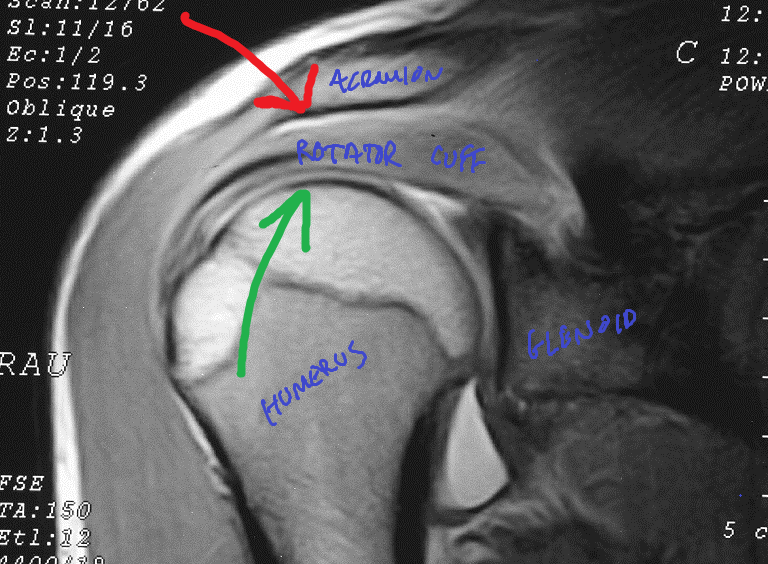

Seeing as the shoulder is one of the more unstable joints, shoulder stability training is imperative for hypermobile trainees.

Adding isometric holds to exercises is another way to increase time-under-tension to bolster tendon and ligament strength. Crawl variations are low-threshold core stabilization exercises that teach you how to stabilize dynamically (during movement). They also are approximation exercises to add to your training. If you want to get fancy, you can add a few chains:

Take care of your tendons!

If you have joint laxity and have/want to avoid joint pain, pay attention to your joint position, balance distraction and approximation exercises, stop stretching so much, and work on your overall stabilization. Own the range of motion you have- don’t push to the full ROM if you don’t need to and risk injury due to instability.

Hypermobility isn’t a curse, it’s actually a pretty cool trait; it just takes a little extra thinking when it comes to training.

Thanks again to Tony for allowing my musings to appear on his blog once again!

About the Author

Kelsey Reed is head strength coach at SAPT Strength & Performance located in Fairfax, VA. Bitten by the iron bug at 16, Kelsey has been lifting ever since. Her love for picking up heavy things spurred her to pursue a degree in the Science of Exercise and Nutrition at Virginia Tech.

Now she spends her days teaching and coaching others in the iron game. In her down time, she lives life on the wild side by not following recipes when she cooks, fighting battles through characters fantasy fiction novels, and attempting to make her cats love her.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches.

Audiences around the world have seen Dr. Evan Osar’s dynamic and original presentations. His passion for improving human movement and helping fitness professionals think bigger about their role can be witnessed in his writing and experienced in every course he teaches.

Erika Mundinger is a licensed Physical Therapist and a board-certified orthopedic specialist working in the Twin Cities area. She practices orthopedics and sports medicine with advanced training and practice in manual therapies, corrective and functional exercises, and treatment of spinal disorders. She works at TRIA Orthopedic Center, the Twin Cities’ premier ortho clinic, treating athletes from professional to “weekend warrior” levels as well as general orthopedics and is a member of the clinic’s Spine Team, helping to better advance patient access to professionals specialized to manage care of spinal disorders and injury.

Erika Mundinger is a licensed Physical Therapist and a board-certified orthopedic specialist working in the Twin Cities area. She practices orthopedics and sports medicine with advanced training and practice in manual therapies, corrective and functional exercises, and treatment of spinal disorders. She works at TRIA Orthopedic Center, the Twin Cities’ premier ortho clinic, treating athletes from professional to “weekend warrior” levels as well as general orthopedics and is a member of the clinic’s Spine Team, helping to better advance patient access to professionals specialized to manage care of spinal disorders and injury.