I often joke I’m the worst handyman in history. Something breaks in our apartment? I’m the first one calling the landlord. A picture needs hanging? My wife is the go to aficionado in that realm.

A task calls for a Phillips screwdriver? Well, I’ll hand you a Phillips screwdriver. I’m not that much of a moron.

That’s the flat head one, right?…;o)

Copyright: tatom / 123RF Stock Photo

Suffice it to say: I am not great at fixing things. As a matter of fact – and at the expense of losing a few points off my man card – the risk of me setting a fire increases exponentially with the arduousness of the task being asked of me.

Replace a knob on a cupboard = relatively safe. The cat may end up with her fur singed, but the building is still standing.

Change oil in the car = Obama may as well hand me the nuclear codes.

Outside of the weight-room I’m a HAZMAT accident waiting to happen. Put me within four walls, however, surrounded by squat racks, deadlift platforms, barbells, kettlebells, selectorized machines, and maybe a movie quality Chewbacca mask for good measure, allow me the opportunity to watch people exercise and gauge movement quality, and I miraculously turn into Gandalf.

I can fix anything.1

Well, I like to think I have a good eye and can catch wonky movement and fix it.

That’s Assuming Something Needs Fixing

I had a very interesting interaction last weekend at CORE. I was contacted by a dude here in Boston who reached out asking if he could stop by the studio to have me look over his squat and to discuss a few ideas that had been reverberating in his head about bar path, acceleration, and power development.

Specifically he noted he was a high-level powerlifter (600+ lb squat at 181) and that he had been tinkering with his technique of late and wanted another set of eyes on him to see if there was something he was missing.

My first thought was “holy fucking shitballs, that’s a sick squat,” and more importantly I felt compelled to tell him “um, just so you know…I’m not a competitive powerlifter and maybe you’d be better off contacting my boys at The Strength House for more detailed badassery?”

“Nah, I respect the way you’re able to analyze movement and feel you take a balanced approach.”

High praise.

What transpired was pretty cool. It was every bit an educational/learning experience for me as it was for him (I think. He left happy).

To Repeat: this guy squats over 600+ at a competing bodyweight of 181 lbs. An advanced lifter indeed. His approach is unconventional to say the least.

Take this little tidbit of our conversation as an example (not taken verbatim, but it’s close):

“So we see guys all the time squatting 225 lbs in the squat rack, often with poor technique, but then are able to walk over to the leg press and perform 800+ lbs for reps. What gives? How is that possible? I thought to myself “there has to be something there.” I train alone in my home gym which allows me all the time in the world to play mad scientist and to tinker with my technique.

Then it dawned on me: why not leg press my squat?”

Of course, in my mind I’m thinking “well the leg press provides a ton more external stability to the body so there’s your answer.” What’s more there’s typically less ROM involved too.

I was intrigued to see this in action nonetheless, anticipating some sort of leg press to squat Transformer to appear.

I ended up witnessing a meticulous set-up, as well as a masterful demonstration of someone who knows what his body is doing at all times. Unconventional without question. But it worked. A few highlights:

- His “low bar” position was lower than low bar position. I’m talking mid-arm.

- Purposeful in-out-in motion of the knees.2

- A flexed spine. In deep hip flexion, he’d go into lumbar flexion.3

- He used a staggered stance (left side was a bit behind the right).

For all intents and purposes, many coaches would look at squat like that and start hyperventilating into a paper bag and immediately go into “I gotta fix this” mode.

Guess what I didn’t fix?

My point: everyone is different. No one has to squat the same way. And he’s an a-hole for being a freak…..;o)

Besides, he squats 600+ freaking lbs. He’s obviously trained himself enough to be able to get into (and out of) precarious situations; and he’s never been hurt or in pain.

It was the last point, though, the staggered stance, that he had never noticed or considered.

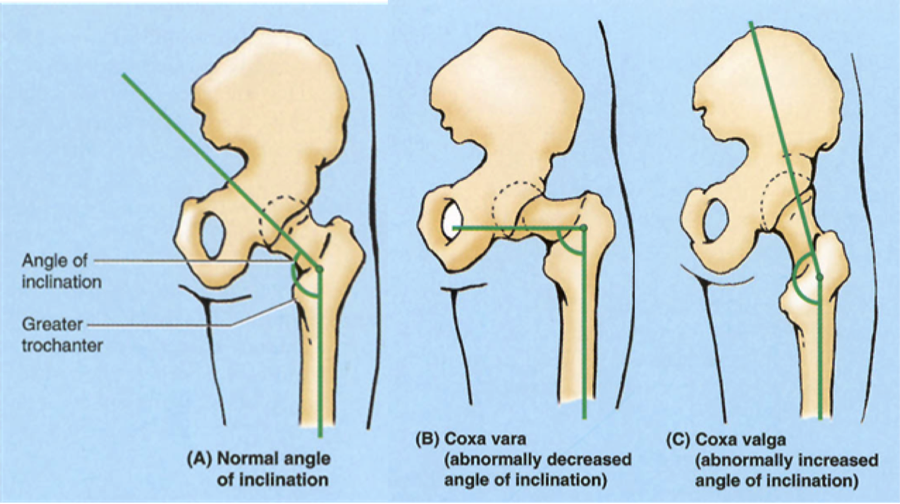

I don’t fall into the camp that says everyone must squat with a symmetrical stance. This defeats the purpose of individuality and respecting each person’s anatomy. When you factor in varying hip anatomy (varying degrees of APT/PPT, how this affects the ability to both flex and extend the hip, anteverted/retroverted acetabulums, anteverted/retroverted femurs, and varying femoral neck lengths), not to mention that you have two of them, not to mention other anthropometrical factors too, like torso length, femur length…it doesn’t take a genius to understand there’s no one right way to squat.

If a certain squat stance, width, depth, (whatever) feels better and more stable, why not run with it?

NOTE: I’d be doing a disservice by not linking to THIS article by Dean Somerset on the topic. He does a much better job at explaining things.

Back to the staggered stance.

600 lb squatter guy was trying to figure out why it seemed he couldn’t keep the barbell over mid-foot on his descent. I noted the staggered stance and he was like, “huh, I never thought of that.”

He then noted how he had always filmed his squats from the RIGHT side. I filmed from the left and his bar path looked to be on point. So maybe he was being a bit overcritical? Maybe the staggered stance evened things out? I’m sure there’s a biomechanical rabbit hole to be explored here (calling Greg Nuckols?).

When To “Fix” Someone’s Squat

I get it: Many of you reading aren’t elite level squatters, and much of the dialogue above has little merit in your training. The bigger picture, though, I think, is to avoid confirmation bias and sticking solely within camps that always agree with you. Everyone is a different, and there’s always more than one way to do something.

Last weekend, for me, was proof of that.

But I’d be remiss not to point out my standard or “comfort zone” is vastly different between an elite lifter and beginner/intermediate lifter.

Elite level lifters get much more leeway to mess up. More to the point: they’ve messed up enough to know what to do to not to mess up. Yeah, that makes sense. When I am coaching a beginner/novice, though, they’re rope for messing up is much, much shorter.

I still feel it’s important to avoid over-coaching and to allow an opportunity for newbies to figure things out.

As a coach, it’s okay to allow clients a window to perform a bad rep. Don’t be quick to correct. Let them figure it out & learn themselves

— Tony Gentilcore (@tonygentilcore1) August 31, 2016

But when it comes to squats I tend to have a few “No-No’s” initially.

1) You Round Your Back, a Part of My Soul Dies

Loaded spinal (end-range) flexion doesn’t do anyone any favors. Pick up a McGill book and join the party. I’d prefer to avoid it as much as possible in the beginning. If I see someone flexing their spine during a squat, it’s my job to figure out why?

From there I’m going to try my best to implement the modality or variation that’s going to best set them up for success.

Much of the time it’s getting someone to appreciate how to adopt a better bracing strategy and stabilize.

- Brace your abs. <— Get “big air” and act as if someone’s going to punch you in the stomach.

- Learning Active vs. Passive Foot, or spreading the floor with your feet (better yet, a cue I stole from Tony Bonvechio is “find the outside of your heels.”

- Brace your abs.4

Full-body TENSION (trying to touch your elbows and pulling down on the bar helps here too) is the name of the game. The sooner a trainee learns this, the sooner he or she will clean up a lot of snafus in their squat technique.

Another easy fix is to implement an anterior load.

This is part of the reason why Goblet Squats or Plate Loaded Squats are so user-friendly and help to maintain a better torso position. The load is in FRONT which then forces the trainee to shift their weight and recruit/engage more of their anterior core, which then helps them remain more upright.

2) Knees Caving In (Past Neutral), Heels Coming Off Ground

The knees caving in aren’t always a deal breaker. Many trainees when they first put a barbell on their back and begin to squat for the first time resemble Bambi taking his first steps.

I don’t mind a little knee movement. Much of the time it’s just a matter of getting some reps in and whammo-bammo, the issue resolves itself.

It’s when it hits the point where they go past neutral and/or the heels come off the ground that it can become problematic.

Some things that have worked for me with knees caving:

- Hey, don’t do that.

- Think of your knee caps tracking with your pinky toe.

- Place a band around the knees to provide some kinesthetic awareness. The band wants to push the knees in, they have to push the band out.

I want a squat to look like a squat. It requires ample ankle dorsiflexion, hip flexion, hip internal/external rotation, t-spine extension, among other things.

When someone’s heels come off the ground it’s often because they have no idea how to hip hinge.

Grooving the hip hinge and using props such as a box (box squats) to get someone to learn to “sit back” and use more of their posterior chain is a nice option. This will help keep the heels cemented to the floor.

NOTE: once they master that, the idea is to then perform an equal parts “knees forward, hips back” motion, learning to sit down into the squat (not so much back, back, back). Again, the squat should look like a squat

And That’s Really It

I’m not TRYING to find something wrong with everyone’s squat.

If the 2-3 things above are met from the get go we’re in a pretty darn good spot.

Things like bar position, foot stance/width, hand position, and everything else in between, while significant considerations for some people and staples for entertaining internet arguments, are all going to depend on several other factors (goals, anatomy, experience, ability level, injury history), and in the grand scheme of things are minute comparatively speaking.

properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.

properly, or even how to stand up from a chair.