First things first: Lets address the obvious. If there were a contest for best blog title of 11/22/16 featuring a kick-ass alliteration starring the letter “D,” I’d totally win it today.

I got the idea the other day after listening to a popular segment on EW Radio called Diva Deep Dive.1

It’s a killer idea and I am woefully unoriginal, so I took it upon myself to steal it and replace the word “Diva” with “Deadlift.” Because deadlift.

The Deficit Deadlift

The deficit deadlift is a variation where the trainee stands on an elevated surface – a plate or some form of platform such as an aerobic stepper or stacked rubber mats – and tries not to shit their spleen lifts a barbell off the ground.

Photo Courtesy of BodyBuilding.com

It’s viewed as more of an accessory movement to the deadlift and is often utilized to address issues with the initial pull off the ground. The idea being the increased ROM (Range of Motion) will make the lift harder and help those who are “slow” off the ground.

Some coaches love it and feel it’s a valuable asset to anyone’s training repertoire, while others hate it and view any of the following…

- Jumping into a live volcano.

- Swallowing a cyanide pill.

- Juggling chainsaws.

- Watching an episode of Downton Abbey.

…as a more valuable use of one’s time.

As with most debates in the health/fitness world the answer always lies somewhere in the middle. So lets break things down shall we?

Origins

I’m pretty sure this particular variation was invented by Ernest Hemingway, but I could be making that up.2 Unlike, say, the Jefferson Deadlift (named after old-time strongman Charles Jefferson) or the Romanian Deadlift (invented by someone from Romania?), no one really knows where the deficit deadlift came from. Besides, who cares, right? The name itself implies what it is.

Unless, and this will blow my effing mind if this is the case, the deficit deadlift IS actually named after someone with the last name Deficit. Man, how ironic would that be?

Addressing the Elephant in the Room

Most of the naysayers of the deficit deadlift will usually chime in with something like “it’s dangerous.” To which I counter…..

There’s no better way for me to chime in on this matter than with this quote from strength coach Andrew Sacks taken from an article he wrote titled Defending the Deficit Deadlift:

“The main argument for dropping the deficit deadlift is that it’s dangerous, and by setting the bar at a height slightly below a traditional deadlift we’re turning a strength-training staple into a lower-back horror movie.

Consider that when we deadlift, the height of the bar is totally arbitrary. Nobody hired scientists to figure out the “ideal” diameter for 45-pound plates. Everybody just agreed that they all should be roughly 17.5 to 18 inches.

So if the diameter of the plates – and therefore the height of the bar – is arbitrary, does it matter where we pull from as long as we maintain form? The short answer is no.”

To that end, I don’t agree that the deficit deadlift is dangerous or that it should be contraindicated altogether. I do agree, however, there are contraindicated lifters, and that a lot of people – due to poor movement quality, anatomical factors, skill level, past or current injury history, and yes, their own stubborn stupidity – are unable to perform this variation with appropriate technique and therefore should avoid it.

^^^ That Stuff I Just Mentioned, Lets Talk About Em

Movement Quality: It’s a rare event when someone walks in on Day #1 and can perform a deficit deadlift flawlessly. I’d argue it’s rare someone can walk in on Day #1 and perform a conventional deadlift flawlessly. It’s human nature to think we’re all better than the average cat. Everyone thinks they’re a better driver than everyone else. It’s likely you’re just as horrendous at parallel parking as the next person.

This sentiment spills over into fitness too. Many people think they’re more advanced than they really are and like to skip over the seemingly “easy” stuff (Kettlebell Deadlift) and catapult themselves into expert level territory (Deficit Deadlift)…despite having the movement quality of a pregnant turtle.

By today’s standards, many people don’t move well and lack the mobility requirements to perform a standard deadlift, let alone one performed from a deficit. Getting down to the barbell requires a fair amount of hip flexion. And if someone lacks it (which is often), the end result is a compromised spinal position into lumbar flexion.

This is where good coaching comes into play. I’d caution people to jump to conclusions too quickly. It is possible to take someone in the picture above and cue them into a better position. However, taking that out of the equation, if it’s already a challenge for someone to bend over towards the bar and not look like their spine is going to break in half, why add more ROM?

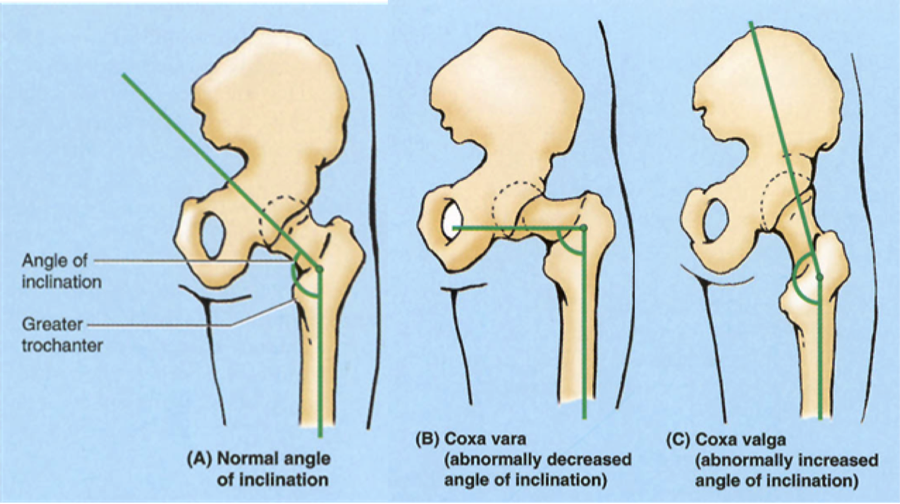

Anatomical Factors: pigging back off the above, we can’t dismiss the idea that everyone is different. There are variations in torso lengths, femur lengths, arm lengths, not to mention bony structure considerations in the hip itself (hip width, acetabulum retroversion/anteversion, how the femoral head sits within the acetabulum (retroversion/anteversion), variations in femoral neck lengths, etc) that make the deficit deadlift a good fit for some people, and not so much for many, many others.

Respecting individual differences is key to long-term success and it’s something you can read more about HERE.

Some people simply won’t have access to the requisite hip flexion necessary to, you know, get into aggressive hip flexion. Unfortunately, none of us are Superman and have X-ray vision…but we can perform a simple Rock-back Screen to ascertain one’s available ROM.

Kneeling Rockback – WIN

Notice I am able to maintain a good spinal position throughout the full-ROM (there’s no “falling” into spinal flexion).

Kneeling Rockback – FAIL

Now we’re in trouble. For someone like this – where losing spinal position happens quickly – it’s likely that going into anything that requires deep(er) hip flexion will be a bad idea.

Again, this doesn’t mean we always have be a Johnny Raincloud. It may be a matter of cueing someone to adopt a better bracing strategy in order to maintain position. If they can do so passively (on the floor) and can then emulate the same ownership actively (standing)…then we know they can access the ROM, we just have to be really diligent with technique and progressing appropriately.

- If they can access passively but not actively, it’s likely a motor control issue or the exercise itself is too much of a novelty.

- If they can’t access it passively, nor can they perform it well actively…we’re likely looking at a structural issue and we need to be more judicious with exercise recommendations.

To the last point, again, adding in more ROM (deficit deadlift) won’t be a good idea.

Skill Level: Call me crazy, but the Deficit Deadlift is an advanced variation.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2kL-7IpYz0

I’d have to be very comfortable with someone’s skill-set and ability before I dumped it into their program. And while it can be viewed as a bit generalist, my “flow” of deadlift progressions are as follows.

Meaning, when starting with a new trainee, here’s how I progress them:

1) Understand that the deadlift = hip hinge. Deadlift doesn’t mean “heavy” or that it has to be loaded at all times or that it has to be done with a barbell.

To that end, we’re going to master the hip hinge.

2) Kettlebell Deadlift (and all it’s variations: Hover Deadlift, 2 KB Deadlift, 1-Arm KB Deadlift, Suitcase Deadlift).

3) Trap Bar Deadlift – first with high-setting, then with low setting. Center of Mass is INSIDE the barbell which makes this a much more lower back and user friendly variations

4) Rack Pulls or Block Pulls

5) Sumo or Modified Sumo Deadlift.

6) Conventional Deadlift

7) Deadlift Whateverthefuck – Deficit Deadlift, Snatch-Grip Deadlift, etc.

Benefits of the Deficit Deadlift

Assuming this variation is “safe,” or a viable options what are the benefits?

1) I’ll concede that the increased ROM has merit, but it’s overplayed. More time under tension is rarely a bad thing, and considering many are weak in their posterior chain, the deficit deadlift is a good fit here.

BUILD THAT BOOTY!

2) I guess it can be argued that the deficit deadlift helps with the initial pull (with regards to the increased ROM). The idea being: make the lift harder and when one reverts back to “normal” ROM things will feel easier.

I’m not opposed to this train of thought. I get it. But to me, if I’m writing a program I want all accessory lifts to address a technique flaw or weakness in one of the big 3 (squat, deadlift, bench press). Making something harder for the sake of making harder won’t necessarily address anything.

Which leads to #3.

3) Being slow or weak off the floor with the deadlift is a thing. However, I find when this is indeed the culprit, utilizing the deficit deadlift here isn’t necessarily all about increasing the ROM as it is about better quadricep recruitment.

We’ve become so posterior chain-centric in the past decade or so that I find a lot of trainees have neglected their quads. And the quads DO play a role in the deadlift; especially with the initial pull (putting force into the ground). This, to me, is the main benefit.

Yes, smarty pants, squatting will help build the quadriceps. But the rule of specificity still reigns supreme. If I want someone to get better at deadlifitng, I’d rather they deadlift (and tweak it accordingly).

Some Closing Thoughts

- As far as how much of a deficit to use: this can be individual, but I find 1-3 inches is more than enough for most trainees. So long as spinal position is maintained.

- I’ll use sub-maximal weight on these (60-75%) for 4-8 reps.

- Deficit deadlifts are aggressive – even for advanced lifters – so I’d caution anyone to use them for more than a few weeks or one training cycle (a month?)

- If know someone with the last name Deficit, please tell me.

just counting reps and throwing some exercises together and calling it a program. It’s training people with an intent to make an impact on their lives.

just counting reps and throwing some exercises together and calling it a program. It’s training people with an intent to make an impact on their lives. Good coaching looks a bit like good parenting. It’s a combination of everything from teaching and motivation to providing boundaries and developing habits…all with a focus on helping the client become a better version of themselves and ultimately achieve their potential. So, coaching is no one thing…it’s a combination of many things.

Good coaching looks a bit like good parenting. It’s a combination of everything from teaching and motivation to providing boundaries and developing habits…all with a focus on helping the client become a better version of themselves and ultimately achieve their potential. So, coaching is no one thing…it’s a combination of many things. nutritional counselling are just a small part of a successful coach-client relationship – “Good Coaching” also considers client education, appreciates the value of effective communication and looks to empower the client in as many ways as possible.

nutritional counselling are just a small part of a successful coach-client relationship – “Good Coaching” also considers client education, appreciates the value of effective communication and looks to empower the client in as many ways as possible. Coaching is about communication of your knowledge of the X’s and O’s of training and programming. So, “good coaching” looks like a good relationship between the trainer and the people they’re currently working with.

Coaching is about communication of your knowledge of the X’s and O’s of training and programming. So, “good coaching” looks like a good relationship between the trainer and the people they’re currently working with.

2nd edition. He thinks foam rolling can help combat muscle creep.

2nd edition. He thinks foam rolling can help combat muscle creep.