Unlike Dan John, I lack the ability to seemingly rattle off an array of quotable quotes with the frequency of a Donald Trump soundbite.

That said, every now and then luck strikes and I chime in with gem like this:

“Lifting weights isn’t supposed to tickle.”

Muscles are going to get sore, and joints are going ache. And, in keeping things real, the risk of sharting yourself increases exponentially.

Sorry, it comes with the territory.

Being “sore and achy,” however, while nothing new to anyone who lifts weights on a regular basis, shouldn’t be a regular occurrence…or badge of honor.

Likewise, while the saying “pain is just weakness leaving the body” is a popular one amongst fitness enthusiasts (most often, CrossFit participants and marathoners1)…it’s really, really, really stupid.

Pain is not weakness leaving the body. It’s your body telling you to “quit the shit” and that what you’re doing has surpassed its ability to recover.

Of course, there are different levels of pain. I can have someone perform a set of 20-rep squats or Prowler drags – on their hands, blindfolded, uphill, for AMRAP – and there’s going to be a degree of “pain” involved.

But if pain is present – to the point where, you know, stuff fucking hurts – then that’s something entirely different and something that needs to be addressed…sans the machismo.

The shoulders are a problem area for many lifters and often take a beating. Below are some brief, overarching talking points on how to address shoulder pain/discomfort.

Note: it’s a broad topic, and one teeny tiny blog post won’t be the answer to everything. However, chances are, addressing one – if not several – of the talking point below may be exactly what’s needed to get the ball rolling in the right direction.

1) Stop Doing What Hurts

I had a client approach me recently about his shoulder. The conversation went something like this:

Client: “My shoulder hurts when I do this.”

[Proceeds to do this weird behind the head, shoulder dislocation thingamajiggy]

Me: “stop doing that.”

Client and Me: “LOL LOL LOL LOL LOL.”

Me: “seriously, stop doing that.”

It seems like an obvious thing to do, but if something hurts – whether it be the weird Cirque du Soleil contortionist move my client was doing, bench pressing, or whatever – stop doing it.

At least for now.

I know it’s a hard blow for a lot of guys to be told to stop bench pressing for any length of time, and in fairness, much of the time it’s a matter of addressing a handful of common technique flaws:

- Better upper back stiffness (learning to pull shoulder blades together and down for improved stability).

- Learning to engage the lats (to make a “shelf” and to “row” the bar down towards the chest).

- Maybe tweaking wrist and elbow position (so one isn’t so flared out).

- Addressing leg drive.

BAM – shoulder doesn’t hurt anymore.

All that said, it’s usually a better play to take out the incendiary movement altogether – maybe for a few days, or even weeks – and take the time to allow tissues to calm down and address any profound weaknesses and dysfunctions present.

2) Earn the Right to Overhead Press

The ability to raise one’s arms overhead – I.e., shoulder flexion – is something that’s not quite as easily accomplished in today’s society.

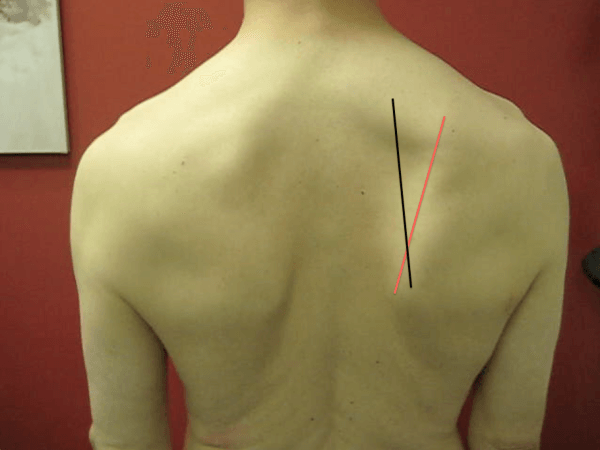

The left: what most people look like (forward head posture, excessive lumbar extension). The Right: dead sexy. Kinda.

We just don’t spend that much time there. Yet, walk into any commercial gym or CrossFit box and you’ll witness any number of trainees happily pushing, hoisting, and/or kipping overhead.

Often with deleterious ramifications.

Several factors come into fruition when discussing the ability to elevate the arms overhead2:

- Shoulder: if one lacks abduction/upward rotation on any given side, you could see any number of compensations like lack of elbow flexion.

- Scapulae: we need upward rotation, protraction, and posterior tilt to get overhead. Most people are lacking in one or all three.

- T-Spine: does it extend? It should.

- Lumbar Spine: does it extend? It sure as shit shouldn’t.

This is where assessment and individualized programming comes into play. Some people require a different “corrective” approach compared to others. However, if that’s not your wheelhouse, refer out!

But as a strength and conditioning professional you could still set people up for success by having them perform more “shoulder friendly” overhead pressing.

1-Arm Landmine Press

Serratus Upward Jab

3) Improve Upward Rotation

Many people are “stuck” in a downwardly rotated position – especially those who participate in an overhead sport (baseball for example) or are a lifetime meathead.

Due to lack of anterior core control, tight/stiff lats, soft tissue restrictions, poor programming balance, or a combination of several factors, many tend to live in a state of “gross” extension.

To that end: anything we can do to target the muscles that help upwardly rotate the scapulae – low/upper traps, serratus – would bode in our favor.

Band Wall Walks

1-Arm Prone Trap Raise

1-Arm Band Overhead Shrug

TRX Hinge Row

Moreover, a little TLC to foam rolling the lats would work wonders, as well as addressing anterior core control/strength with exercises like deadbugs.

Too, proper coaching/cueing by not allowing clients to crank though their TL junction or lumbar spine during movement would be stellar. Thanks, appreciate it.

4) Obligatory Commentary On How Breathing Will Cure Everything

I’m a believer in PRI (Postural Restoration Institute) principles and have used it to great success with clients in the past and present.

Helping to “reset” posture with focused breathing drills can be a game changer – especially for those living with shoulder pain.

First, lets address a common fallacy…beautifully articulated by NYC-based physical therapist, Connor Ryan:

PRI is not about learning how to move, it’s about breaking patterns driven by threat & chronic stress, allowing a window for learning

— Connor Ryan (@CRyanPT) February 2, 2016

Taking the conversation on “gross extension” a little further, we can attempt to apply Connor’s analogy with some focused breathing drills like this:

Doing so:

- Helps stimulate parasympathetic activity (excessive extension = “impingement” of Posterior Mediastinum leading to constant sympathetic – flight or flight – activity).

- Allows a window for the thorax/rib-cage to move, which, in turn, allows the scapulae to move.

- I only perform 1-3 different drills here, lasting, maybe, 2-4 minutes. And then it’s time to go lift heavy shit.

5) Let Your Shoulder Blades Move

A common mistake I see many trainees make is “glueing” their shoulder blades in place during exercises like a 1-arm dumbbell row or even push-ups.

This is not wise.

Scapular retraction (adduction) is important, but so it allowing the shoulder blades to protract (abduct).

In short: the shoulder blades should have the ability to move around the rib cage.

If their always pinned in place, this will often manifest into glenohumeral issues – namely, anterior humeral translation and instability.

Translated into non-geek speak, your shoulder is basically saying:

Simple Shoulder Solution

Strength coach Max Shank just released a handy manual called the Simple Shoulder Solution.

Much of what I discussed above mirrors much of what Max covers in this manual (with more detail).

In order to best address the function of the shoulder you need to follow the order of operations and handle the surrounding structures first. These are:

1) Breathing and Core Activation

2) Thoracic and Neck Mobility

3) Scapular Mobility and Stability

4) Glenohumeral Mobility and Stability

The main idea here is that if you do not address 1-3 FIRST, you are likely to create more compensation, hypermobility and potential for injury at the Glenohumeral joint.

I can dig it.

Give it a look for yourself HERE.

I’m not going to hit on every point above today. I’d encourage you to check out Mike Reinold’s site and/or look into his and Eric Cressey’s

I’m not going to hit on every point above today. I’d encourage you to check out Mike Reinold’s site and/or look into his and Eric Cressey’s