I’ve been a fan of “offset” loading for a number of years now. Without getting too deep in the weeds on what offset loading is and what the benefits are…

…it’s when you either stagger your foot or hand position on certain exercises OR you load an exercise a certain way (how you hold a DB or KB) to target or overload a specific limb or joint.

It has implications for both rehab (helping people to move better) AND for getting them jacked (self-explanatory). My good friend and Boston-based colleague, Dr. Michelle Boland, elaborates more on offset loading and how you can use it to your clients’ advantage below.

Enjoy.

Never Question Your Exercise Selection Again

I speak from personal experience, as a personal trainer, when I say it can be challenging to navigate through all of your client’s aches, pains, and movement hiccups.

It has caused me some serious headaches in the past.

In a social media guru filled world, there is so much information about magic tricks to FIX your clients movement struggles. These magic tricks are typically called corrective exercises.

We then think we are Harry Potter and build our client’s sessions and training programs around corrective exercises, making the perfect potion to have our clients move perfectly.

BUT, what ends up happening is that our FITNESS TRAINING sessions start feeling like a bad physical therapy experience.

- Our clients are not TRULY becoming better movers.

- Our clients are not TRULY gaining muscle or looking better in a bathing suit.

They are in no man’s land, not getting results, and being held back from their physical potential.

. Not to worry though!

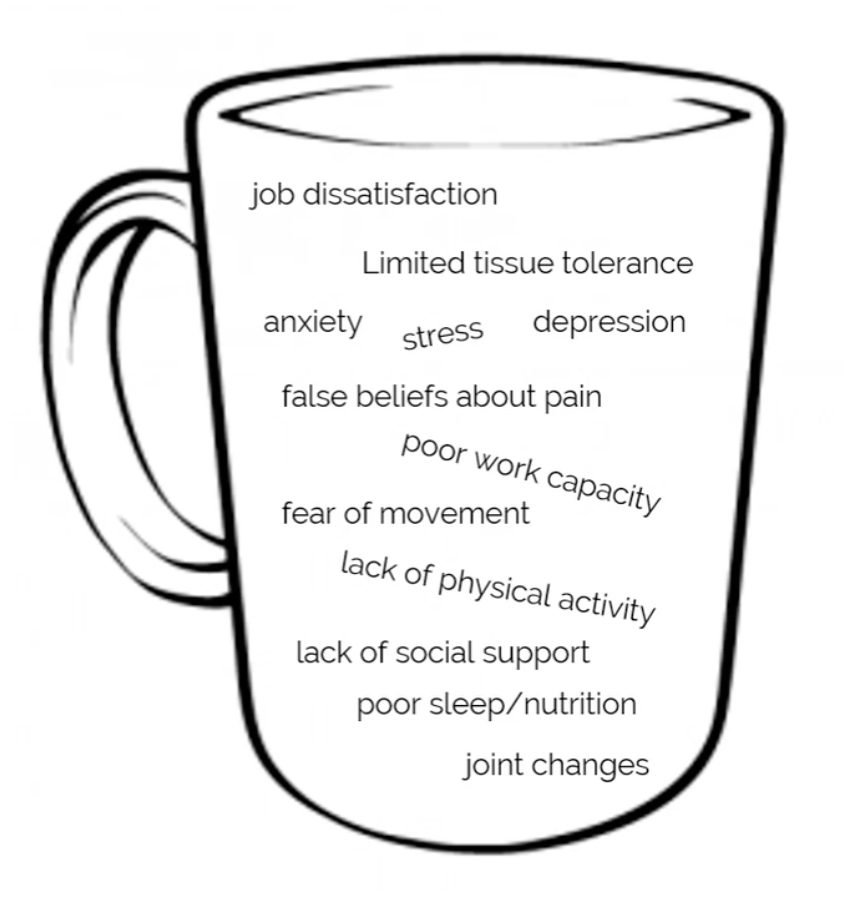

(Check out THIS blog post to learn more about the mental barriers that may be holding your clients back.)

I am here to help!! Because I made these same mistakes and learned from them!

I am going to provide you with four simple rules to make sure your clients are still achieving their fitness goals while ALSO becoming better movers.

These rules will provide you the ability to build a training program and select exercises without having to choose between a simple corrective exercise that is targeted to help someone move better and a complex lift that is targeted to get them jacked.

Most coaches’ have go-to exercises for getting jacked and strong which is great but these same exercises can also create some movement restrictions due to the high levels of tension they require, such as a barbell back squat or bench press.

However, simple considerations to where the weight is placed, the type of grip, and feet position (stance) can be changed during these typical go-to exercises to prevent some of the possible movement restrictions.

Below, I am going to provide you with simple, practical programming strategies that will allow you to both load AND improve movement quality for all ages and training levels.

The four simple rules allow you to make small tweaks to exercises in order to help people move better, WHILE still getting 80-90% of a training effect from the loading. In other words, we can still get our clients strong and powerful without turning them into walking refrigerators.

(If you prefer to watch instead of read, Check out my video presentation of these Rules HERE.)

Rule 1. Choose Offset Positions

Offset positions include separating hands and feet from front to back. These positions will allow your clients to feel stable, so they can still try hard, without robbing them of their rotational abilities along the way.

Offset positions benefits include:

- Improving rotational abilities from separating hands and feet front to back which helps to turn people’s hips and chests

- Initiates alternating positions of the hips with one hip more extended and the opposite hip more flexed

- Provides greater variation in your exercise selection especially for unilateral loading

- Provides more options to add different weight shifting which helps to create unilateral loading challenges

Offset positions include:

1. The Staggered Stance position is standing with both feet flat on the ground and split front to back. Feet are typically hip-width apart from side to side and a half foot distance apart front to back, but the distance can be altered in relation to base of support needs. So, if your client has a difficult time balancing in this position, move their feet wider side to side. The position initiates alternating positions of the pelvis with one hip more extended and the opposite hip more flexed and can also create rotation towards the back side leg.

The Staggered Stance position can also be challenged with a variation called the ‘Loaded Step’. The Loaded Step variation is a weight distribution backwards onto the back leg. The center of mass should be about 80% on the back leg and 20% on the front leg.

Loaded Step benefits:

- This position variation encourages rotation through the hips and chest

- You can coach it to be a knee or hip dominant exercise (see examples below)

- You will feel LOTS of inner thigh (adductor), glute, and hamstring on the back leg

- It supports hip mobility and eases tight posterior hips by allowing someone to feel a stretch in the back leg posterior hip, but try to avoid squeezing glutes…I know how tempting this can be 😉

- It encourages more single leg loading or shared loading

2. The Split Stance position is standing with a front to back separation of the legs and includes a reduction of foot contact on the back side foot. The leg separation is wider front to back than the Staggered Stance position and there is removal of full foot contact on the back side foot, such that the back heel is off the ground and the weight is rolled onto the ball of the foot. The position mimics (not equivalent to) a top of a split squat exercise.

The Staggered Stance position can be challenged with a variation called the ‘Kickstand Step’. The Kickstand Step Split Stance variation position is a body weight distribution forwards on the front leg with supportive, light weight on the back toe. Body weight distribution should be about 80% on the front leg and 20% on the back leg.

Kickstand Step Consideration and Benefits:

- This position variation encourages more single leg loading

- This position variation encourages rotation through the hips and chest

- You will feel LOTS of inner thigh (adductor), glute, and hamstring on the front leg

You can challenge the position with where you hold the weight:

Holding Weight With Two Hands Will Limit Rotation

Holding Weight In Opposite Hand As Front Leg Will Encourage More Rotation

3. The Staggered Hand position is a front to back separation of the hands on the ground. Staggering the hands can help with creating alternating movement in the ribcage. The side of the ribs of the back hand will be lower and the upper body will be more likely to be rotated in that direction. You can also help target more side abdominal wall muscles by staggering the hands.

Check out some exercises you can start incorporating today with offset positions:

Contralateral Loaded Step Hip Hinge

Loaded Step Ski Erg

1-Arm Kickstand KB Swing

Staggered KB Hang Clean

Offset Pushup

Salamander Pushups For Staggered Hands

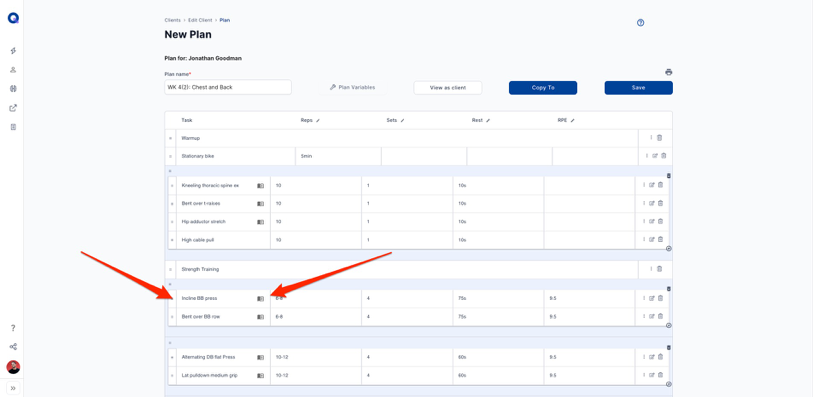

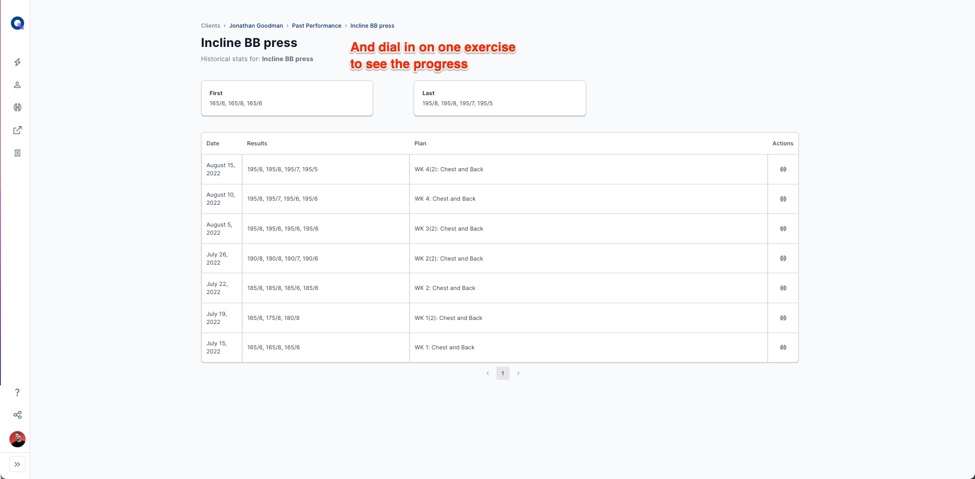

Rule 2. Choose Offset Loading

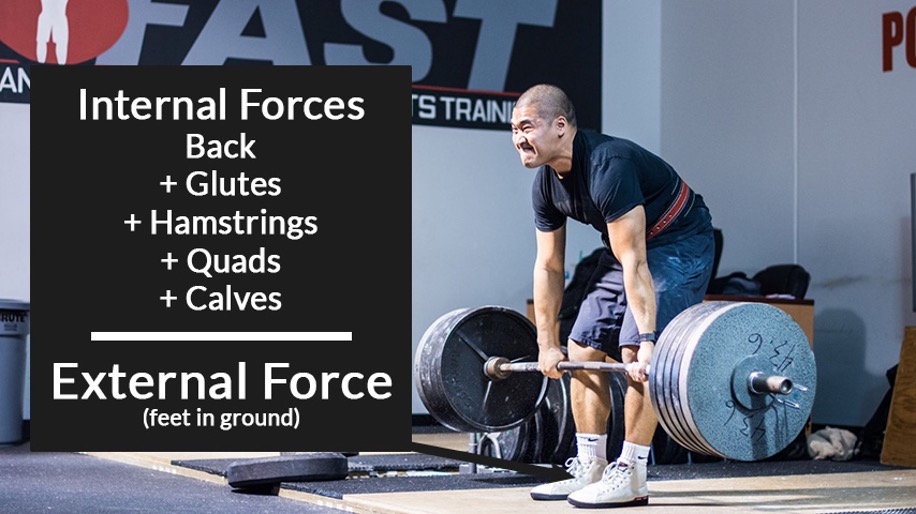

Offset loading involves having your clients hold weight in less than obvious places that will challenge them in different ways. For example, instead of putting a barbell on your back, hold the barbell between your elbows (see Zercher hold below).

Holding a weight in the front will help target more abdominal wall muscles with less low back issues (see Goblet hold below). Instead of holding a kettlebell with two hands, you can also hold it with one hand to create some unilateral loading challenges.

Check out some exercises you can start incorporating today with offset loading:

KB Goblet Split Squat

Contralateral 1-Arm KB Split Squat w/ Opposite Arm Reach

DB Zercher Split Squat

Alternating 1-Arm KB Deadlift

Rule 3. Alternate Grips

Alternating your grip on the weights can improve your client’s ability to rotate, making them super athletes while ALSO being able to pick up heavy things and put them down. Turning one hand into supination and the other hand into pronation causes the upper body to turn towards one side.

Check out some exercises you can start incorporating today with alternating grips:

Jefferson Split Squat

Alternating Grip Pull-Up

Rule 4. Reduce Tension When It Is Not Necessary

Have you ever had a client who picks up five pound dumbbells to do a bicep curl and acts like they are 60 pound dumbbells?

I sure have.

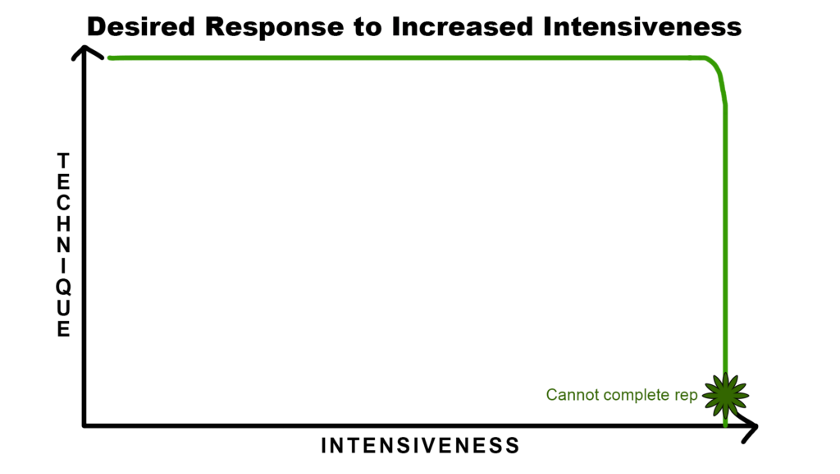

Encourage clients to create tension and substantial effort WHEN THEY HAVE TO.

Other times, encourage them to back off a bit. Exercises that are not too demanding can encourage improvements to joint range of motion and movement quality IF they are performed with low tension, no squeezing, no death grips, or no breath holding.

Your clients do not need to be squeezing all of their muscles, all of the time, to get a good workout. Low tension exercises can stretch tight areas and improve mobility. For example, the Loaded Step RDL can improve hip mobility and stretch the back side of the hip when it is performed with low weight and low levels of tension.

Loaded Step RDL

A great start would be to select warm-up or cool-down exercises that can be performed with low tension!

QUICK Programming Tips To Incorporate These RULES:

- Combine: Every exercise within your training session include the above four rules

- Pair: Pair a heavy, bilateral lift with an exercise that incorporates the rules

- Consider positions in your exercise selection process, to learn more click HERE.

Summary

Incorporating offset positions, offset loading, and alternating grips into your exercise selection will help your clients gain some rotational abilities, gain hip and rib cage mobility, and add some excitement into their training while STILL allowing them to get strong.

To learn more, check out my EXERCISE SELECTION PROCESS which layers positions, fitness qualities, then individualized variations. Position selection is the foundation of my exercise selection and all the information included in this article about offset positions comes from my quick and concise Position Principles course.

The Position Principles course will help you to avoid leaving behind the greatest factor in getting your clients and athletes to move better. The course provides clarity on positional biomechanics, clarity on terminology within the fitness industry for exercises, a downloadable programming template, and easy steps to organize your program design. After this course, you will never question your exercise selection again.

If you have any comments or questions please feel free to email me at [email protected].

If you enjoyed the exercise videos in this article, check out the MBT Exercise Database for 1,200 more videos to use, embed within your programming, and level up your exercise selection game.

Author: Dr. Michelle Boland

- Owner of Michelle Boland Training

- PhD in Exercise Physiology

- Instagram @dr.michelleboland

- Check out Michelle’s Free Training Program Considerations Handbook!

Elsbeth Vaino is a personal trainer and gym owner at Custom Strength in Ottawa, Canada, where she and her team primarily train regular people who don’t love the gym but do like what going to the gym allows them to do. Before becoming a trainer, she worked as an electronic warfare engineer (you know, same old story). Check her out on Instagram (

Elsbeth Vaino is a personal trainer and gym owner at Custom Strength in Ottawa, Canada, where she and her team primarily train regular people who don’t love the gym but do like what going to the gym allows them to do. Before becoming a trainer, she worked as an electronic warfare engineer (you know, same old story). Check her out on Instagram (